爱丁堡大学信息学院课程笔记 Parallel Programming Language and Systems, Informatics, University of Edinburgh

Reference: http://www.inf.ed.ac.uk/teaching/courses/ppls/ CMU 15213: Introduction to Computer Systems (ICS) Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective A Comprehensive MPI Tutorial Resource A chapter on MPI from Ian Foster’s online Book Designing and Building Parallel Programs

Introduction to parallel computer architecture

Covering some of the nasty issues presented by the shared memory model, including weak consistency models and false sharing in the cache, and some architectural issues for the multicomputer model.

Bridging the gap between the parallel applications and algorithms which we can design and describe in abstract terms and the parallel computer architectures (and their lowest level programming interfaces) which it is practical to construct.

The ability to express parallelism (a.k.a concurrency) concisely, correctly and efficiently is important in several contexts: • Performance Computing: parallelism is the means by which the execution time of computationally demanding applications can be reduced. In the era of static (or even falling) clock speeds and increasing core count, this class is entering the computing mainstream. • Distributed Computing: when concurrency is inherent in the nature of the system and we have no choice but to express and control it. • Systems Programming: when it is conceptually simpler to think of a system as being composed of concurrent components, even though these will actually be executed by time-sharing a single processor.

Parallel Architecture

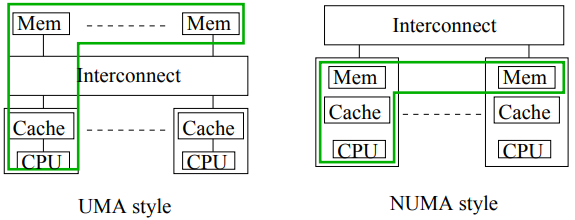

Two types (mainstream):

- Shared Memory architectures: in which all processors can physically address the whole memory, usually with support for cache coherency (for example, a quad or oct core chip, or more expensive machines with tens or hundreds of cores)

- Multicomputer architectures: in which processors can only physically address their “own” memory (for example, a networked cluster of PCs), which interact with messages across the network.

Increasingly, systems will span both classes (e.g. cluster of manycore, or network-onchip manycores like the Intel SCC), and incorporate other specialized, constrained parallel hardware such as GPUs.

Real parallel machines are complex, with unforseen semantic and performance traps. We need to provide programming tools which simplify things, but without sacrificing too much performance.

Shared Memory Architectures

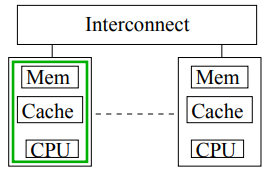

Uniform Memory Access (UMA) architectures have all memory “equidistant” from all CPUs.

For NUMA performance varies with data location. NUMA is also confusingly called Distributed Shared Memory as memory is physically distributed but logically shared.

Memory consistency challenge: when, and in what order should one processor public updates to the shared memory? Exactly what and when it is permissible for each processor to see is defined by the Consistency Model, which is effectively a contract between hardware and software, must be respected by application programmers (and compiler/library writers) to ensure program correctness.

Different consistency models trade off conceptual simplicity against cost (time/hardware complexity):

- Sequential consistency: every processor “sees” the same sequential interleaving of the basic reads and writes. This is very intuitive, but expensive to implement.

- Release consistency: writes are only guaranteed to be visible after program specified synchronization points (triggered by special machine instructions). This is less intuitive, but allows faster implementations.

Shared memory architectures also raise tricky performance issues: The unit of transfer between memory and cache is a cache-line or block, containing several words. False sharing occurs when two logically unconnected variables share the same cache-line. Updates to one cause remote copies of the line, including the other variable, to be invalidated.

Multicomputer architectures

Lack of any hardware integration between cache/memory system and the interconnect. Each processor only accesses its own physical address space, so no consistency issues. Information is shared by explicit, co-operative message passing

Performance/correctness issues include the semantics of synchronization and constraints on message ordering.

Performance/correctness issues include the semantics of synchronization and constraints on message ordering.

Parallel Applications and Algorithms

Three well-known parallel patterns: Bag of Tasks, Pipeline and Interacting Peers.

Here using the co, < >, await notation.

在co oc内的代码, 顺序是任意的.

# 这里暂时用 // 表示并行的代码

co

a=1; // a=2; // a=3; ## all happen at the same time, What is a in the end?

oc

To answer the above question, we need to define Atomic Actions: Reads and writes of single variables as being atomic. For more than one statements, if they appear to execute as a single indivisible step with no visible intermediate states, they are atomic, must be enclosed in < >.

a=0;

co

a=1; // a=2; // b=a+a; ## what is b?

oc

The above code has no < >, each value accessed in an expression is a read. Each assignment is a write. Thus, b could be 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4.

a=0;

co

a=1; // a=2; // <b=a+a;>

oc

Now the only outcomes for b are 0, 2 or 4.

Sequential memory consistency (SC) To make agreement on such inconsistency, we define the sequential memory consistency (SC), to be consistent with the following rules:

- ordering of atomic actions (particularly reads and writes to memory) from any one thread have to occur in normal program order

- atomic actions from different threads are interleaved arbitrarily (ie in an unpredictable sequential order, subject only to rule 1)

It doesn’t mean that SC programs have to be executed sequentially! It only means that the results we get must be the same as if the program had been executed in this way.

Await

The await notation < await (B) S > allows us to indicate that S must appear to be delayed until B is true, and must be executed within the same atomic action as a successful check of B.

a=0; flag=0;

co

{a=25; flag=1;}

//

<await (flag==1) x=a;> ## x = 25

oc

However, it is not guaranteed that, an await statement is executed right after its condition becomes true. If other atomic actions make the condition false again, before the await executes, it will have to wait for another chance.

The Bag-of-Tasks

Example: Adaptive Quadrature, compute an approximation to the shaded integral by partitioning until the 梯形 trapezoidal approximation is “good enough”, compared with the sum of its two sub-divided trapezoidals’s area.

area = quad (a, b, f(a), f(b), (f(a)+f(b))*(b-a)/2);

The recursive calls to quad do not interfere with each other. So we can parallelize the program by changing the calls to

# 简单地并行

co

larea = quad(left, mid, f(left), f(mid), larea); //

rarea = quad(mid, right, f(mid), f(right), rarea);

oc

In practice, there is very little work directly involved in each call to quad. The work involved in creating and scheduling a process or thread is substantial (much worse than a simple function call), program may be swamped by this overhead.

Using the Bag of Tasks pattern: a fixed number of worker processes/threads maintain and process a dynamic collection of homogeneous “tasks”. Execution of a particular task may lead to the creation of more task instances.

# Bag of Tasks pattern

co [w = 1 to P] {

while (all tasks not done) {

get a task;

execute the task;

possibly add new tasks to the bag;

}

}

1, Shared bag: contains task(a, b, f(a), f(b), area)

2, Get a task: remove a record from the bag, either:

• adds its local area approximation to the total

• or creates two more tasks for a better approximation (by adding them to the bag).

Advantage: 1, It constraints the number of processes/threads to avoid overhead. 2, Useful for independent tasks and to implement recursive parallelism 3, Naturally load-balanced: each worker will probably complete a different number of tasks, but will do roughly the same amount of work overall.

Bag of Tasks Implementation: The challenge is to make accessing the bag much cheaper than creating a new thread. With a shared address space, a simple implementation would make the bag an atomically accessed shared data structure.

shared int size = 1, idle = 0;

shared double total = 0.0;

bag.insert (a, b, f(a), f(b), approxarea);

co [w = 1 to P] {

while (true) {

< idle++; >

< await ( size > 0 || idle == P ) ## 检测 termination

if (size > 0) { ## get a task

bag.remove (left, right ...); size--; idle--;

} else break; > ## the work is done

mid = (left + right)/2; ..etc.. ## compute larea, etc

if (fabs(larea + rarea - lrarea) > EPSILON) { ## create new tasks

< bag.insert (left, mid, fleft, fmid, larea);

bag.insert (mid, right, fmid, fright, rarea);

size = size + 2; >

} else < total = total + larea + rarea; >

}

}

Detecting termination: 不能仅仅因为 bag 空了就认为可以结束了, 因为还可能有还在工作的 workers 未来会产生新的任务. 所以需要让 workers 有能力把自己的工作完成状况告知 bag. When bag is empty AND all tasks are done; All tasks are done when all workers are waiting to get a new task.

If a bag of tasks algorithm has terminated, there are no tasks left. However, the inverse is not true. I.e. no tasks in a bag could mean that one of the workers is still processing a task which can lead to creation of multiple new tasks. To solve this problem, workers could have the ability to notify the master/bag once they finish the current task. As a result, an implementation of bag of tasks can then contain a count of idle and active works to prevent early termination

A more sophisticated implementation (with less contention) might internally have a collection of bags, perhaps one per worker, with task-stealing to distribute the load as necessary.

With message passing, a simple scheme might allocate an explicit “farmer” node to maintain the bag. Again, a more sophisticated implementation could distribute the bag and the farmer, with task-stealing and termination checking via messages.

Pipeline Patterns.

Example: The Sieve of Eratosthenes algorithms for finding all prime numbers.

To find all prime numbers in the range 2 to N. The algorithm write down all integers in the range, then repeatedly remove all multiples of the smallest remaining number. Before each removal phase, the new smallest remaining number is guaranteed to be prime.

Notice that, it is not necessarily to wait one Sieve completed then start another. As long as one Sieve stage finds out one candidate number could not be divided exactly by the sieve number, it could generate a new stage with this candidate number as Sieve. And different sieve just remove the multiples of its own Sieve number.

# a message-passing style pipeline pseudocode

main() { # the generator

spawn the first sieve process;

for (i=2; i<=N; i++) {

send i to first sieve;

}

send -1 to first sieve; # a "stop" signal

}

sieve() {

int myprime, candidate;

receive myprime from predecessor and record it;

do {

receive candidate from predecessor;

if (candidate == -1) {send -1 to successor if it exists}

else if (myprime doesn't divide candidate exactly) {

if (no successor yet) spawn successor sieve process;

send candidate to successor sieve process;

}

} while (candidate != -1)

}

每一个数(2-N)都可能作为筛子, 筛掉能整除这个筛子的其他数,而筛子之间是互相独立的,所以可以以流水线模式 pipeline patterns来并行操作,动态生成筛子。最开始最小的数字2会成为筛子。筛子可以理解为不同的工序,其余数字从小到大逐一通过这些工序加工(在 Sieve of Eratosthenes 问题中变为筛选排查),无法被筛子整除的数字会被传递到下个筛子(如果没有下一个筛子,则以这个数字创建新的筛子),这样保证生成的筛子就都是素数了。虽然工序是按顺序过的,但是所有工序可以同时对不同的产品(数字)开工,从而达到并行目的。

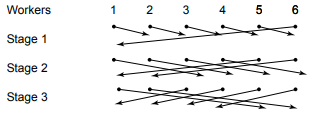

For pipeline patterns, the potential concurrency can be exploited by assigning each operation (stage of the pipeline) to a different worker and having them work simultaneously, with the data elements passing from one worker to the next as operations are completed. Despite the dependencies (order constraints) of the processing steps, the pipeline threads can work in parallel by applying their processing step to different data (products).

Think of pipeline patterns as the factory assembly line. We need to pick out prime number from a range of numbers N, each number is passed into a sequence of stages, each stages checks a pass in number based on the stages’s Sieve. The numbers that finally pass all stages without being removed is a prime number.

Pipelines are composed of a sequence of threads, in which each thread’s input is the previous thread’s output, (Producer-Consumer relationships).

The advantages of pipeline patterns is that construction of pipeline stages is dynamic and data-dependent.

To allow production and consumption to be loosely synchronized, we will need some buffering in the system.

The programming challenges are to ensure that no producer overwrites a buffer entry before a consumer has used it, and that no consumer tries to consume an entry which doesn’t really exist (or re-use an already consumed entry)

Interacting Peers Pattern

Models of physical phenomena are often expressed as a system of partial differential equations. These can be approximately solved by “finite difference methods” which involve iteration on a matrix of points, in an interacting peers pattern. The “compute” step usually involves only a small number of neighbouring points. The termination test looks for convergence.

We could use a duplicate grid and barriers to enforce correct synchronization between iterations:

shared real grid[n+2, n+2], newgrid[n+2, n+2];

shared bool converged; local real diff;

co [i = 1 to n, j = 1 to n] {

initialise grid;

do {

barrier(); ## before resetting test

converged = true; ## provisionally

newgrid[i,j] = (grid[i-1,j] + grid[i+1,j] +

grid[i,j-1] + grid[i,j+1])/4; ## compute new value

diff = abs (newgrid[i,j] - grid[i,j]); ## compute local change

barrier(); ## before converged update

if (diff > EPSILON) converged = false; ## any one will do

grid[i,j] = newgrid[i,j]; ## copy back to real grid

barrier(); ## before global check

} while (not converged);

}

A barrier() in ppls makes any thread that arrive here has to wait all the other threads arriving here.

以方腔热对流的模拟计算模型为例,每个网格节点$(i,j)_{t+1}$ 的更新依赖于上一个迭代时间点的$(i,j)_t$以及其临近几个点的值,创建最多跟网格点数量一样的threads,然后并行地计算网格点的新值,更新的值用一个buffer层来缓存,用barrier()来保证所有网格点的更新值都计算完毕,再检查收敛情况,再用一个barrier()保证所有buffer层的值都更新到原网格上,再决定是否进行下一次计算。

Single Program Multiple Data (SPMD): A programming style, all processes execute more or less the same code, but on distinct partitions of the data.

Other Patterns

Other candidate patterns include MapReduce (championed by Google), Scan, Divide & Conquer, Farm as well as application domain specific operations.

Shared Variable Programming

In the shared-memory programming model, tasks share a common address space, which they read and write asynchronously. An advantage of this model from the programmer’s point is that the notion of data “ownership” is lacking, so there is no need to specify explicitly the communication of data between tasks. Program development can often be simplified.

There are two fundamentally different synchronization in shared variable programming. Mutual Exclusion and Condition Synchronization.

Mutual Exclusion

Atomic actions, at most one thread is executing the critical section at a time. Prevent two or more threads from being active concurrently for some period, because their actions may interfere incorrectly. For example, we might require updates to a shared counter (e.g., count++) to execute with mutual exclusion.

Critical Sections problem

A simple pattern of mutual exclusion occurs in the critical section problem - when n threads execute code of the following form, in which it is essential that at most one thread is executing statements in the critical section at a time (because of potentially unsafe access to shared variables)

co [i = 1 to n] {

while (something) {

lock(l); #entry section

critical section;

unlock(l); #exit section

non-critical section;

}

}

Design code to execute before (entry protocol) and after (exit protocol) the critical section to make the critical section atomic. If one thread lock the critical section, no one(thread) else could lock it or unlock it anymore, until the thread unlock it.

Important properties:

- Mutual exclusion: When a thread is executing in its critical section, no other threads can be executing in their critical sections.

- Absence of Deadlock (or Livelock): If two or more threads are trying to enter the critical section, at least one succeeds.

A deadlock is a state in which each member of a group is waiting for some other member to take action, such as sending a message or more commonly releasing a lock, so that neither of them take action. 类似两个人相遇互不相让, 没人肯挪动. Livelock is a condition that takes place when two or more programs change their state continuously, with neither program making progress. 类似两个人相遇同时往相同方向避让.

- Absence of Unnecessary Delay: If a thread is trying to enter its critical section and the other threads are executing their non-critical sections, or have terminated, the first thread is not prevented from entering its critical section.

- Eventual Entry (No Starvation): A thread that is attempting to enter its critical section will eventually succeed. May not matter in some “performance parallel” programs - as long as we are making progress elsewhere.

Simple implementation of each lock with a shared boolean variable: if false, then one locking thread can set it to true and be allowed to proceed. Other attempted locks must be forced to wait.

# model assumes that the l = false;

# write is already atomic

# This might fail if the model is more relaxed than SC.

lock_t l = false;

co [i = 1 to n] {

while (something) {

< await (!l) l = true; > # guarantee the others waiting

critical section;

l = false; # unlock the lock, open the critical section

non-critical section;

}

}

To implement the < await (!l) l = true; >, we rely on some simpler atomic primitive, implemented with hardware support. There are many possibilities, including “Fetch-and-Add”, “Test-and-Set” and the “Load-Linked, Store-Conditional” pairing.

Test-and-Set (TS) instruction

Behaving like a call-by-reference function, so that the variable passed in is read from and written to, but in reality it is a single machine instruction. The key feature is that this happens (or at least, appears to happen) atomically.

# A Test-and-Set (TS) instructionW

bool TS (bool v) {

< bool initial = v;

v = true;

return initial; >

}

lock_t l = false;

co [i = 1 to n] {

while (something) {

while (TS(l)) ; ## spin lock

critical section;

l = false;

non-critical section;

}

}

This is called spin lock,

Simple spin locks don’t make good use of the cache (those spinning Test-And-Sets play havoc with contention and coherence performance). A pragmatically better spin locks is known as Test-and-Test-and-Set - mainly spinning on a read rather than a read-write function.

...

while (something) {

while (l || TS(l)); /* only TS() if l was false*/

critical section;

...

}

...

Simply read l until there is a chance that a Test-and-Set might succeed.

Spin lock guarantees mutual exclusion, absence of deadlock and absence of delay, but does not guarantee eventual entry.

Lamport’s Bakery Algorithm

Implement critical sections using only simple atomic read and simple atomic write instructions (i.e. no need for atomic read-modify-write).

采用商店结账排队机制,顾客就是一个个threads,根据排队码,越小的优先级越高(0 除外,0 代表没有结账需求),最小的可以进入critical section。

The challenge is entry protocal, if a thread intends to access the critical section:

- 排队取号:It sets its turn

turn[i] = max(turn[:])+1(Threads not at or intend to access the critical section have a turn of 0) - 等待叫号:This thread waits until its turn comes up (until it has the smallest turn).

int turn[n] = [0, 0, ... 0];

co [i=1 to n] {

while (true) {

turn[i] = max (turn[1..n]) + 1;

for (j = 1 to n except i) {

while ((turn[j]!=0 and (turn[i] > (turn[j])) skip;

}

critical section;

turn[i] = 0;

noncritical section;

}

}

因为max (turn[1..n]) + 1不是atomic的, 所以会出现问题.

问题一: if turn setting is not atomic then two (or more) threads may claim the same turn.

两个threads在取号阶段

turn[i] = max(turn[:])+1出现并发,两个都先max, 之后再+1.

问题二: there is possibility that a thread can claim a lower turn than another thread which enters the critical section before it!

两个threads在取号阶段

turn[i] = max(turn[:])+1出现并发, 并且在两个threads分别进行max的间隙, 刚好在CS中的thread完成并退出CS,导致两个thread看到的max值不一样了. 前者比后者看到的大, 但前者却因为更早进行+1操作而提前进入了CS.

举例:假如同时有三个thread A B C, A 已经在CS中(turn(A)>0):

- B 先运行max比较(

max = turn(A)), - C 在 A 退出后(

turn(A) = 0)才进行比较(max = 0), - B 先进行

+1操作(turn(B) = turn(A)+1 > 1), - B 进行比较后允许进入CS (此时turn(C)还是0, 0是被忽略的);

- 之后C才

+1(turn(C) = 0 + 1 = 1); - 这样导致B的值虽然比C大, 但B还是比C先进入CS; 之后因为 C 的 turn 比较小, 所以 C 也跟着进入 CS。

问题一解决方案 - 使用线程ID(绝不相同)做二次区分, 在相同 turn 的情况下,具有较低ID的 thread 有限。

问题二解决方案 - 在max (turn[1..n]) + 1之前先turn[i] = 1;.

• 这样,任何 threads 想取号都要先标记为 1

• 标记后,才有资格跟其他 thread 比较

• 以max+1作为号码进入队列,这样任何的可能的 turn 值都必定大于 1

• B 无法提前进入CS (此时turn(C)不再是被忽略的0, 而是最小正整数1).

# (x, a) > (y,b) means (x>y) || (x==y && a>b).

while (true) {

turn[i] = 1; turn[i] = max (turn[1..n]) + 1;

for (j = 1 to n except i) {

while ((turn[j]!=0 and (turn[i], i) > (turn[j], j)) skip;

}

...

}

Lamport’s algorithm has the strong property of guaranteeing eventual entry (unlike our spin lock versions). The algorithm is too inefficient to be practical if spin-locks are available.

Condition Synchronization

Delay an action until some condition (on the shared variables such as in producer-consumer, or with respect to the progress of other threads such as in a Barrier) becomes true.

Barrier synchronization

Barrier synchronization is a particular pattern of condition synchronization, a kind of computation-wide waiting:

co [i = 1 to n] {

while (something) {

do some work;

wait for all n workers to get here;

}

}

A Counter Barriers

<count = count + 1;>

<await (count == n);>

is fine as a single-use barrier, but things get more complex if (as is more likely) we need the barrier to be reusable.

改良为<await (count == n); count = 0;>也不行: an inter-iteration race, 假如count == n, 那么n个threads都完成了前面的statements并准备执行await, 但其中任何一个 thread 先执行完整个代码都使count = 0,这样剩余的threads就无法通过await条件了.

Sense Reversing Barrier

A shared variable sense is flipped after each use of the barrier to indicate that all threads may proceed. 关键每个 thread 都有自己的 private variable mySense 和 while spin lock。解决了前面的死锁问题。

shared int count = 0; shared boolean sense = false;

co [i = 1 to n] {

private boolean mySense = !sense; ## one per thread

while (something) {

do some work;

< count = count + 1;

if (count == n) { count = 0; sense = mySense; } ## flip sense

>

while (sense != mySense); ## wait or pass

mySense = !mySense; ## flip mySense

// 或者使用 < await (sense==mySense) mySense = !sense;>

}

}

所有thread的local variable mySense开始都被赋值为!sense(true),前面n-1个thread都得在内循环while那里等着;直到最后一个thread完成工作后, if条件才满足, count重置为0, 反转sense(被赋值为mySense也即是true), 之后所有threads才能结束内部while循环,接着再次反转sense(被赋值为!mySense也即是false), 然后进行下一轮大循环,借此达到重复利用barrier的目的. sense初始值是什么无所谓, 反转才是关键.

缺点:$O(n)$效率,count次数(同步次数)正比于thread数量。

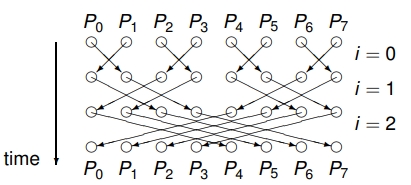

Symmetric Barriers

Symmetric barriers are designed to avoid the bottleneck at the counter. 通过 pair-threads barriers 多轮同步来构建一个完整的 n-threads barriers,让所有threads都知道大家已经完成任务。总共是$\log_2n$ 轮同步。每个thread在完成必要工作后, 开始进入下面的pairwise同步环节,自己(myid)的初始arrive状态为0:

# arrive[i] == 1 means arrive barrier

# there will be log_2 #threads stages,

# 每个stage代表一次pairwise同步

for [s = 0 to stages-1] {

<await (arrive[myid] == 0);> # 1

arrive[myid] = 1; # 2

work out who my friend is at stage s;

<await (arrive[friend] == 1);> # 3

arrive[friend] = 0; # 4

}

这样保证了,每个thread需要先把自己的arrive状态标记为1(#1,#2),才可以去看同伴的状态(#3),假如同伴也是1,那么表明自己这一组是都到达了barrier状态(大家都是1),那么就会把对方的状态初始化为0 (#4),进入下一阶段,更换同伴,继续同步比较。

When used as a step within a multistage symmetric barrier, 会出现问题:假如有四个thread,那么就会有两个stages:第一次是1和2同步,3和4同步。2一直没到barrier,1一直卡在#3。而3和4 同步完后开始检查1的状况,发现

When used as a step within a multistage symmetric barrier, 会出现问题:假如有四个thread,那么就会有两个stages:第一次是1和2同步,3和4同步。2一直没到barrier,1一直卡在#3。而3和4 同步完后开始检查1的状况,发现arrive[1] = 1,就运行Lines (3) and (4), 结果1就被初始化了,而2还没是没到barrier。

解决办法是给每个stage分配新的arrive变量。

for [s = 0 to stages-1] {

<await (arrive[myid][s] == 0);>

arrive[myid][s] = 1;

work out who my friend is at this stage;

<await (arrive[friend][s] == 1);>

arrive[friend][s] = 0;

}

这样假如出现2一直没到barrier的情况, 那么1会卡在当前stage, 1的stage+1的arrive状态就无法更新为1.

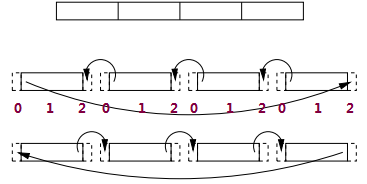

Dissemination Barriers

If n isn’t a power of 2, instead of pairwise synchs, we have two partners at each stage for each thread, one incoming and one outgoing.

Structured Primitives

Instead of implementing directly in the user-address space, a number of more structured primitives have been devised for implementation with the assistance of the operating system, so that threads can be directly suspended and resumed by the OS’s scheduler.

• Machine code, instructions and data directly understandable by a CPU; • Language primitive, the simplest element provided by a programming language; • Primitive data type, a datatype provided by a programming language.

Semaphores 信号灯

A semaphore is a special shared variable, accessible only through two atomic operations, P(try to decrease) and V(increase), defined by:

P(s): <await (s>0) s=s-1;>

V(s): <s=s+1;>

Property: A thread executing P() on a 0 valued semaphore will be suspended on a queue until after some other thread has executed a V().

Application: A semaphore appears to be a simple integer. A thread waits for permission to proceed a critical section, and then signals that it has proceeded by performing a P() operation on the semaphore.

Binary semaphore: A semaphore whose usage is organised to only ever take the value (0, 1) as a mutex 互斥. Counting(split) semaphore: can take on arbitrary nonnegative values.

Semaphores still require careful programming: there is no explicit connection in the program source between “matching” semaphore operations. It is easy to get things wrong.

Similarly, there is no obvious indication of how semaphores are being used - some may be for mutual exclusion, others for condition synchronization. Again confusion is possible.

Semaphores for Critical Section (mutual exclusion)

sem mutex = 1;

co [i = 1 to n] {

while (whatever) {

P(mutex);

critical section;

V(mutex);

noncritical section;

}

}

Semaphores for Barrier Synchronisation

实现 symmetric barrier: an array of arrive semaphores for each stage

for [s = 1 to stages] {

V(arrive[myid][s]);

work out who my friend is at stage s;

P(arrive[friend][s]);

}

Semaphores for Producer-Consumer Buffering

针对单个producer和consumer,控制其接触单个容量的buffer权限:一个semaphores标识buffer已满full,一个标识空empty。这种情况下,只能有一个semaphore是1,故称之为split binary semaphore。 P(full) 执行 wait full > 0 : full -= 1, V(empty)执行empty += 1

T buf; sem empty = 1, full = 0;

co

co [i = 1 to M] {

while (whatever) {

...produce new data locally

P(empty);

buf = data; # producer

V(full);

} }

//

co [j = 1 to N] {

while (whatever) {

P(full);

result = buf; # consumer

V(empty);

... handle result locally

} }

oc

Bounded Buffer: Control access to a multi-space buffer (the producer can run ahead of the consumer up to some limit)

- Implement the buffer itself with an array (circular),

- and two integer indices, indicating the current front and rear of the buffer and use arithmetic modulo

n(the buffer size), so that the buffer conceptually becomes circular - For a single producer and consumer, we protect the buffer with a split “counting” semaphore, initialised according to the buffer size.

- Think of full as counting how many space in the buffer are full, and empty as counting how many are empty

T buf[n]; int front = 0, rear = 0;

sem empty = n, full = 0;

co ## Producer

while (whatever) {

...produce new data locally

P(empty); # empty>0, 才能生产, empty-=1

buf[rear] = data; rear = (rear + 1) % n;

V(full);

}

// ## Consumer

while (whatever) {

P(full); # full>0, 才能消耗, full-=1

result = buf[front]; front = (front + 1) % n;

V(empty);

... handle result locally

}

oc

Multiple Producers/Consumers: Because each producer may access the same pointer to overide each other, so as consumer. Thus we need two levels of protection.

- Use a split counting semaphore to avoid buffer overflow (or underflow), as previously.

- Use a mutual exclusion semaphores to prevent interference between producers (and another to prevent interference between consumers). This allows up to one consumer and one producer to be actively simultaneously within a non-empty, non-full buffer.

T buf[n]; int front = 0, rear = 0; 86

sem empty = n, full = 0, mutexP = 1, mutexC = 1;

co

co [i = 1 to M] {

while (whatever) {

...produce new data locally

P(empty);

P(mutexP); # stop the other producers from accessing the buffer

buf[rear] = data; rear = (rear + 1) % n;

V(mutexP);

V(full);

} }

//

co [j = 1 to N] {

while (whatever) {

P(full);

P(mutexC);

result = buf[front]; front = (front + 1) % n;

V(mutexC);

V(empty);

... handle result locally

} }

oc

Extending Multiple Producers/Consumers: If the buffered items are large and take a long time to read/write, we would like to relax this solution to allow several producers and/or consumers to be active within the buffer simultaneously.

- We need to ensure that these workers accesse distinct buffer locations, which require the index arithmetic to be kept atomic.

- Make sure that the producer/consumers wait for that element to be empty/full before actually proceeding.

The solution is to have extra semaphores pair for each buffer location.

Monitors

The monitor is a more structured mechanism which allows threads to have both mutual exclusion and the ability to wait (block) for a certain condition to become true. It has a mechanism for signaling other threads that their condition has been met. A monitor consists of a mutex (lock) object and condition variables (cv). A condition variable is basically a container of threads that are waiting for a certain condition.

For Mutual Exclusion: i.e. a mutex (lock) object, ensures that at most one thread is active within the monitor at each point in time. 不同线程的下一条即将执行的指令 (suspended) 可能是来自同一个 monitor (由os自行分配), 但同一时间内,至多只能有一个线程执行下一条指令,但可能不同线程各自收到了来自这个 monitor 代码的不同指令. It is as if the body of each monitor method is implicitly surrounded with P() and V() operations on a single hidden binary semaphore, shared by all methods.

For Condition Synchronization, using a cv with a monitor to control a queue of delayed threads by a kind of Signal and Continue (SC) scheme.

For a condition_variables x;

wait(x): Release lock; wait for the condition to become true; reacquire lock upon return (Java wait())Signal(x): Wake up a waiter, if any (Java notify())signal-all(x)orBroadcast(x): Wake up all the waiters (Java notifyAll())

For the thread active inside a monitor method - executing in monitor state

- If the thread could not proceed, it may call the

wait(cv)operation to give up the (implicit) lock it holds on the monitor, and being suspended (push to the end of CV queue). Each CV has its unique block queue. - Or the thread could calls the operation

signal(cv)to release the lock. This allow one previously blocked thread (normally chosen by a FIFO discipline) to become ready for scheduling again (only one will be allowed to enter the monitor entry queue at a time). The signalling thread continues uninterrupted. - Or

return().

If no threads are waiting, then a signal() is “lost” or “forgotten”, whereas a V() in Semaphores allows a subsequent P() to proceed.

Monitor semantics mean that when a thread which was previously blocked on a condition is actually awakened again in the monitor.

The point to remember is that when the signal happened, the signalled thread was allowed to try to acquire the monitor lock again). It could be that some other thread acquires the lock first, and does something which negates the condition again (for example, it consumes the “new item” from a monitor protected buffer).

Thus it is often necessary, in all but the most tightly constrained situations, to wrap each conditional variable wait() call in a loop which rechecks the condition it was waiting for is still true.

Single producer, single consumer bounder buffer

monitor Bounded_Buffer {

typeT buf[n]; # an array of some type T

int front = 0, # index of first full slot

rear = 0; # index of first empty slot

count = 0; # number of full slots

## rear == (front + count) % n

condition_variables not_full, # signaled when count < n

not_empty; # signaled when count > 0

procedure deposit(typeT data) { # 存

while (count == n) wait(not_full);

buf[rear] = data; rear = (rear+1) % n; count++;

signal(not_empty);

}

procedure fetch(typeT &result) { # 取

while (count == 0) wait(not_empty);

result = buf[front]; front = (front+1) % n; count--;

signal(not_full);

}

}

Why the while loop is necessary as a safety check on the wait calls (why not use if)? - 因为notify()只会让正在 wait queue 的 thread 进入准备状态, 但不会直接控制其恢复工作(是否马上开始,谁先开始,都是由os内部控制的), 所以导致不同 thread 进度不同; 而while可以保证当即使 thread 因为受到notify()而结束wait()开始进入准备状态(entry queue)后, 继续检查 buffer 状态, 这样假如发现自己是最优先安排的那个, 就可以跳出while循环进入工作状态; 假如发现自己优先度不是最高的(while循环条件继续满足), 则继续wait().

The key difference to semaphores: signal() on a condition variable is not “remembered” in the way that V() on a semaphore is. If no threads are waiting, then a signal() is “lost” or “forgotten”, whereas a V() will allow a subsequent P() to proceed.

Real Shared Variable Programming Systems

Various concepts for shared variable programming have been embedded in real programming systems. In particular C’s Posix threads (Pthreads) library and Java’s threads and monitors.

POSIX Threads (Pthread)

Create a new thread: Threads (type pthread_t) begin by executing a given function, and terminate when that function exits (or when killed off by another thread).

int pthread_create (pthread_t *thread, p_thread_attr_t *attr,

void *(*function) (void *), void *arguments);

Wait for thread termination: int pthread_join (pthread_t t, void ** result);

//一个简单但是有错误的例子,

int target;

void *adderthread (void *arg) {

int i;

for (i=0; i<N; i++) {

target = target+1;

}

}

int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {

int i; pthread_t thread[P];

target = 0;

for (i=0; i<P; i++) {

pthread_create(&thread[i], NULL, adderthread, NULL);

} .....

}

Variable target is accessible to all threads (shared memory). Its increment is not atomic, so we may get unpredictable results.

POSIX provides mechanisms to coordinate accesses including semaphores and building blocks for monitors.

Pthreads semaphores

//用 pthread semaphores 改写前面的代码

sem_t lock;

void *adderthread (void *arg) {

int i;

for (i=0; i<N; i++) {

sem_wait(&lock);

target = target+1;

sem_post(&lock);

}

}

int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {

target = 0;

sem_init(&lock, 0, 1);

.....

}

sem_init(&sem, share, init), where init is the initial value and share is a “boolean” (in the C sense) indicating whether the semaphore will be shared between processes (true) or just threads within a process (false).sem_wait(s), which is the Posix name for P(s)sem_post(s), which is the Posix name for V(s)

A Producers & Consumers:

sem_t empty, full; // the global semaphores

int data; // shared buffer

int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {

pthread_t pid, cid;

....

sem_init(&empty, 0, 1); // sem empty = 1

sem_init(&full, 0, 0); // sem full = 0

pthread_create(&pid, &attr, Producer, NULL);

pthread_create(&cid, &attr, Consumer, NULL);

pthread_join(pid, NULL);

pthread_join(cid, NULL);

}

void *Producer (void *arg) {

int produced;

for (produced = 0; produced < numIters; produced++) {

sem_wait(&empty);

data = produced;

sem_post(&full);

}

}

void *Consumer (void *arg) {

int total = 0, consumed;

for (consumed = 0; consumed < numIters; consumed++) {

sem_wait(&full);

total = total+data;

sem_post(&empty);

}

printf("after %d iterations, the total is %d (should be %d)\n", numIters, total, numIters*(numIters+1)/2);

}

Pthreads Monitors

Pthreads provides locks, of type pthread_mutex_t m;. These can be

- Initialized with

pthread_mutex_init(&m, attr), where attr are attributes concerning scope (as with semaphore creation). If attr isNULL, the default mutex attributes (NONRECURSIVE) are used; - Locked with

pthread_mutex_lock(&m), which blocks the locking thread ifmis already locked. There is also a non-blocking versionpthread_mutex_trylock(&m). - Unlocked with

pthread_mutex_unlock(&m). Only a thread which holds a given lock, should unlock it!

Pthreads provides condition variables pthread_cond_t. As well as the usual initialization, these can be:

- Waited on with

pthread_cond_wait(&cv, &mut)wherecvis a condition variable, andmutmust be a lock already held by this thread, and which is implictly released. - Signalled with

pthread_cond_signal(&cv)by a thread which should (but doesn’t strictly have to) hold the associated mutex. The semantics are “Signal-and-Continue” as previously discussed. - Signalled all with

pthread_cond_broadcast(&cv). This is “signal-all”

A simple Jacobi grid-iteration program with a re-usable Counter Barrier. To avoid copying between “new” and “old” grids, each iteration performs two Jacobi steps. Convergence testing could be added as before.

pthread_mutex_t barrier; // mutex semaphore for the barrier

pthread_cond_t go; // condition variable for leaving

int numArrived = 0;

void Barrier() {

pthread_mutex_lock(&barrier);

numArrived++;

if (numArrived == numWorkers) {

numArrived = 0;

pthread_cond_broadcast(&go);

} else {

pthread_cond_wait(&go, &barrier);

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&barrier);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

pthread_t workerid[MAXWORKERS];

pthread_mutex_init(&barrier, NULL);

pthread_cond_init(&go, NULL);

InitializeGrids();

for (i = 0; i < numWorkers; i++)

pthread_create(&workerid[i], &attr, Worker, (void *) i);

for (i = 0; i < numWorkers; i++)

pthread_join(workerid[i], NULL);

}

void *Worker(void *arg) {

int myid = (int) arg, rowA = myid*rowshare+1, rowB = rowA+rowshare-1;

for (iters = 1; iters <= numIters; iters++) {

for (i = rowA; i <= rowB; i++) {

for (j = 1; j <= gridSize; j++) {

grid2[i][j] = (grid1[i-1][j] + grid1[i+1][j] + grid1[i][j-1] + grid1[i][j+1]) * 0.25;

}

}

Barrier();

for (i = rowA; i <= rowB; i++) {

for (j = 1; j <= gridSize; j++) {

grid1[i][j] = (grid2[i-1][j] + grid2[i+1][j] + grid2[i][j-1] + grid2[i][j+1]) * 0.25;

}

}

Barrier();

}

}

Memory Consistency in Pthreads

Weak consistency models can wreck naive DIY synchronization attempts!

To enable portability, Pthreads mutex, semaphore and condition variable operations implicitly act as memory fences, executing architecture specific instructions.

In effect, the C + Pthreads combination guarantees a weak consistency memory model, with the only certainties provided at uses of Pthreads primitives.

For example, all writes by a thread which has released some mutex, are guaranteed to be seen by any thread which then acquires it. Nothing can be assumed about the visibility of writes which cannot be seen to be ordered by their relationship to uses of Pthread primitives.

The programmer must also be careful to use only thread-safe code, which works irrespective of how many threads are active.

Thread-safe code only manipulates shared data structures in a manner that ensures that all threads behave properly and fulfill their design specification without unintended interaction. Implementation is guaranteed to be free of race conditions when accessed by multiple threads simultaneously.

Typical problems involve the use of non-local data. For example, imagine a non-thread safe malloc. Unluckily interleaved calls might break the underlying free space data structure. Some libraries will provide thread-safe versions (but of course, which pay an unnecessary performance penalty when used in a single threaded program).

Java Concurrency

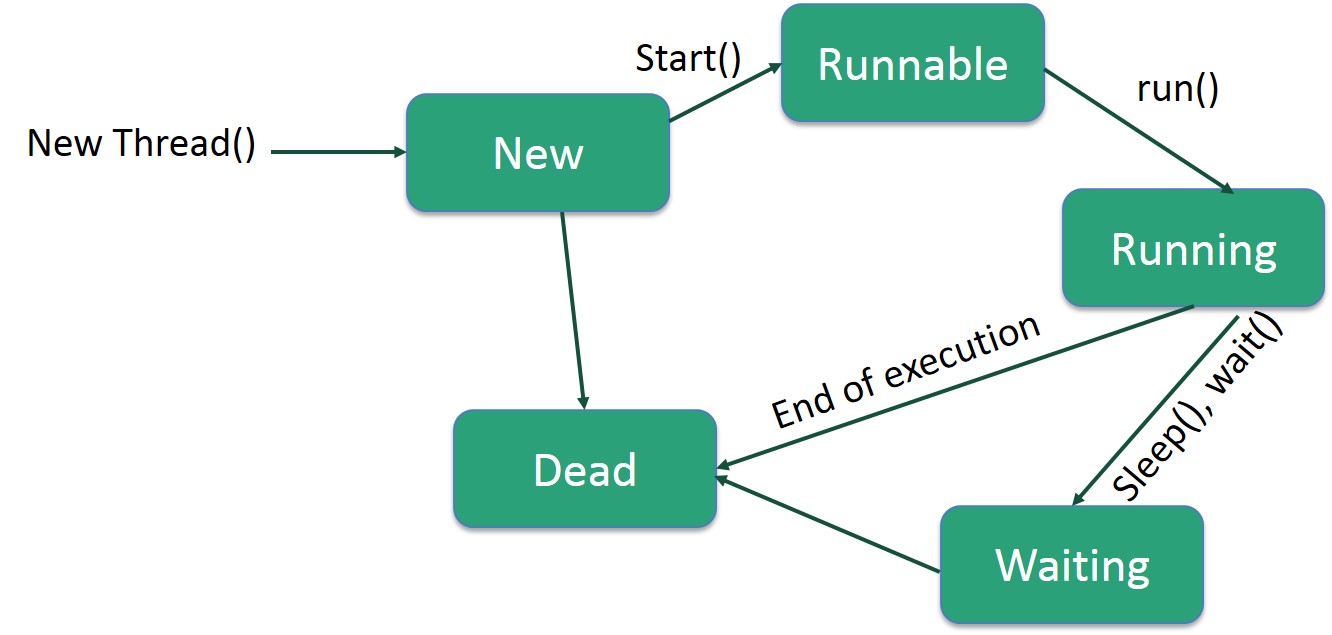

Java是一种多线程 multi-threaded 编程语言,其同步模型是基于 monitor 概念,可用于开发多线程程序。多任务 multtasking 就是多个进程共享公共处理资源(如CPU)的时候。多线程将多任务的思想扩展到可以将单个应用程序中的特定操作细分为单独线程的应用程序。每个线程都可以并行运行。操作系统不仅在不同的应用程序之间分配处理时间,而且在应用程序内的每个线程之间分配处理时间。

Java Threads

Threads can be created from classes which extend

Threads can be created from classes which extend java.lang.Thread

class Simple extends Thread {

public void run() {

System.out.println("this is a thread");

}

}

new Simple().start(); // implicitly calls the run() method

Or implement java.lang.Runnable (so we can extend some other class too).

class Bigger extends Whatever implements Runnable {

public void run() { .... }

}

new Thread( new Bigger (...) ).start();

Wait to join with another thread

class Friend extends Thread {

private int me;

public Friend (int i) { me = i; }

public void run() {

System.out.println("Hello from thread " + me);

}

}

class Hello throws java.lang.InterruptedException {

private static final int n = 5;

public static void main(String[] args) {

int i; Friend t[] = new Friend[n];

System.out.println ("Hello from the main thread");

for (i=0; i<n; i++) {

t[i] = new Friend(i);

t[i].start();

}

for (i=0; i<n; i++) {

t[i].join(); // might throw java.lang.InterruptedException

}

System.out.println ("Goodbye from the main thread");

}

}

Java “Monitors”

Java provides an implementation of the monitor concept (but doesn’t actually have monitor as a keyword).

Any object in a Java program can, in effect, become a monitor, simply by declaring one or more of its methods to be synchronized, or by including a synchronized block of code.

Each such object is associated with one, implicit lock. A thread executing any synchronized code must first acquire this lock. This happens implicitly (i.e. there is no source syntax). Similarly, upon leaving the synchronized block the lock is implicitly released.

Java’s condition variable mechanism uses Signal-and-Continue semantics (The signalling thread continues uninterrupted). Each synchronizable object is associated with a single implicit condition variable. Manipulated with methods wait(), notify() and notifyAll(). We can only have one conditional variable queue per monitor (hence the absence of any explicit syntax for the condition variable itself).

wait(): has three variance, one which waits indefinitely for any other thread to call notify or notifyAll method on the object to wake up the current thread. Other two variances puts the current thread in wait for specific amount of time before they wake up.

notify(): wakes up only one thread waiting on the object and that thread starts execution.

notifyAll(): wakes up all the threads waiting on the object, although which one will process first depends on the OS implementation.

These methods can be used to implement producer consumer problem where consumer threads are waiting for the objects in Queue and producer threads put object in queue and notify the waiting threads.

Readers & Writers problem requires control access to some shared resource, such that there may be many concurrent readers, but only one writer (with exclusive access) at a time.

/* 2 readers and 2 writers making 5 accesses each

with concurrent read or exclusive write. */

class ReadWrite { // driver program -- two readers and two writers

static Database RW = new Database(); // the monitor

public static void main(String[] arg) {

int rounds = Integer.parseInt(arg[0],10);

new Reader(rounds, RW).start();

new Reader(rounds, RW).start();

new Writer(rounds, RW).start();

new Writer(rounds, RW).start();

}

}

class Reader extends Thread {

int rounds; Database RW;

private Random generator = new Random();

public Reader(int rounds, Database RW) {

this.rounds = rounds;

this.RW = RW;

}

public void run() {

for (int i = 0; i<rounds; i++) {

try {

Thread.sleep(generator.nextInt(500));

} catch (java.lang.InterruptedException e) {}

System.out.println("read: " + RW.read());

} }

}

class Writer extends Thread {

int rounds; Database RW;

private Random generator = new Random();

public Writer(int rounds, Database RW) {

this.rounds = rounds;

this.RW = RW;

}

public void run() {

for (int i = 0; i<rounds; i++) {

try {

Thread.sleep(generator.nextInt(500));

} catch (java.lang.InterruptedException e) {}

RW.write();

} }

}

Implement the “database”. Allowing several readers to be actively concurrently. The last reader to leave will signal a waiting writer.

Thus we need to count readers, which implies atomic update of the count. A reader needs two protected sections to achieve this.

Notice that while readers are actually reading the data they do not hold the lock.

class Database {

private int data = 0; // the data

int nr = 0;

// synchronized means no more than one thread could do that

private synchronized void startRead() { nr++; }

private synchronized void endRead() {

nr--;

if (nr==0) notify(); }// awaken a waiting writer

public int read() {

int snapshot;

startRead();

snapshot = data; // read data

endRead();

return snapshot;

}

public synchronized void write() {

int temp;

while (nr>0)

try { wait(); } catch (InterruptedException ex) {return;}

temp = data; // next six lines are the ‘‘database’’ update!

data = 99999; // to simulate an inconsistent temporary state

try { Thread.sleep(generator.nextInt(500)); // wait a bit, for demo purposes only

} catch (java.lang.InterruptedException e) {}

data = temp+1; // back to a safe state

System.out.println("wrote: " + data);

notify(); // awaken another waiting writer

}

}

We could express the same effect with synchronized blocks

public int read() {

int snapshot;

synchronized(this) { nr++; } // this - the database object

snapshot = data;

synchronized(this) {

nr--;

if (nr==0) notify(); // awaken a waiting writer

}

return snapshot;

}

Would it be OK to use notifyAll() in read()? - Yes, but with extra transmission cost.

Buffer for One Producer - One Consumer

/** (borrowed from Skansholm, Java from the Beginning) */

public class Buffer extends Vector {

public synchronized void putLast (Object obj) {

addElement(obj); // Vectors grow implicitly

notify();

}

public synchronized Object getFirst () {

while (isEmpty())

try {wait();} catch (InterruptedException e) {return null;}

Object obj = elementAt(0);

removeElementAt(0);

return obj;

}

}

The java.util.concurrent package

Including a re-usable barrier and semaphores (with P() and V() called acquire() and release()). It also has some thread-safe concurrent data structures (queues, hash tables).

The java.util.concurrent.atomic package provides implementations of atomically accessible integers, booleans and so on, with atomic operations like addAndGet, compareAndSet.

The java.util.concurrent.locks package provides implementations of locks and condition variables, to allow a finer grained, more explicit control than that provided by the built-in synchronized monitors.

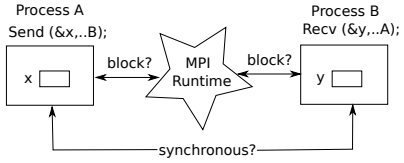

Message Passing Programming

When the underyling archictecture doesn’t support physically shared memory (for example, by distributing the OS and virtual memory system, i.e. Multicomputer architectures), we can make the disjoint nature of the address spaces apparent to the programmer, who must make decisions about data distribution and invoke explicit operations to allow interaction across these.

Message passing, which is a approache to abstract and implement such a model, dominates the performance-oriented parallel computing world.

Message passing is characterized as requiring the explicit participation of both interacting processes, since each address space can only be directly manipulated by its owner. The basic requirement is thus for send and receive primitives for transferring data out of and into local address spaces.

The resulting programs can seem quite fragmented: we express algorithms as a collection of local perspectives. These are often captured in a single program source using Single Program Multiple Data (SPMD) style, with different processes following different paths through the same code, branching with respect to local data values and/or to some process identifier.

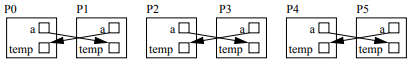

// SPMD Compare-Exchange

co [me = 0 to P-1] { // assumes P is even

int a, temp; // these are private to each process now

......

// typical one step within a parallel sorting algorithm

if (me%2 == 0) {

send (me+1, a); // send from a to process me+1

recv (me+1, temp); // receive into temp from process me+1

a = (a<=temp) ? a : temp; // 取较小值

} else {

send (me-1, a);

recv (me-1, temp);

a = (a>temp) ? a : temp; // 取较大值

} ......

}

1, Synchronization: Must a sending process pause until a matching receive has been executed (synchronous), or not (asynchronous)? Asynchronous semantics require the implementation to buffer messages which haven’t yet been, and indeed may never be, received. If we use synchronous semantics, the compare-exchange code above will deadlock. Can you fix it?

1, Synchronization: Must a sending process pause until a matching receive has been executed (synchronous), or not (asynchronous)? Asynchronous semantics require the implementation to buffer messages which haven’t yet been, and indeed may never be, received. If we use synchronous semantics, the compare-exchange code above will deadlock. Can you fix it?

One way s to make the send be a non-blocking one (

MPI_Isend) Another way is to reverse the order of one of the send/receive pairs:

} else {

recv (me-1, temp);

send (me-1, a);

a = (a>temp) ? a : temp; // 取较大值

} ......

2, Addressing: When we invoke a send (or receive) do we have to specify a unique destination (or source) process or can we use wild-cards? Do we require program-wide process naming, or can we create process groups and aliases?

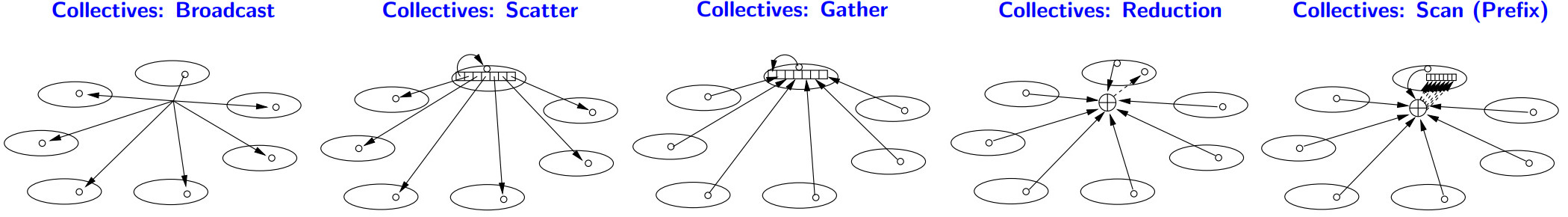

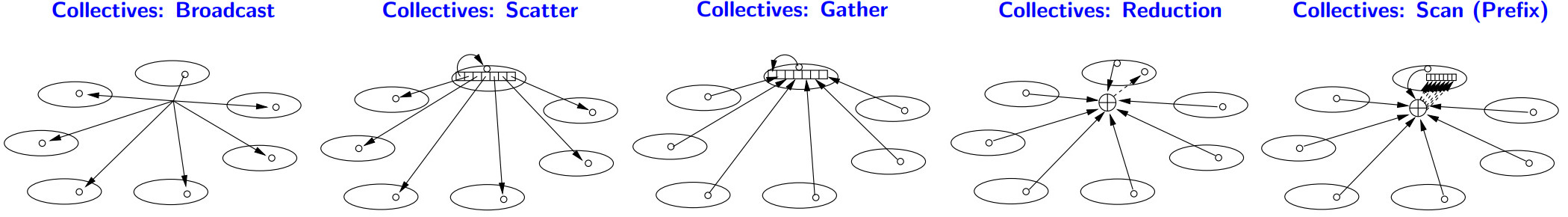

3, Collective Operations: Do we restrict the programmer to single-source, single-destination, point-to-point messages, or do we provide abstractions of more complex data exchanges involving several partners? • Broadcast: Everyone gets a copy of the same value.

• Scatter: Data is partitioned and spread across the group.

• Gather: Data is gathered from across the group.

• Reduction: Combine the gathered values with an associative operation.

• Scan (Prefix): Reduce and also compute all the ordered partial reductions.

• Broadcast: Everyone gets a copy of the same value.

• Scatter: Data is partitioned and spread across the group.

• Gather: Data is gathered from across the group.

• Reduction: Combine the gathered values with an associative operation.

• Scan (Prefix): Reduce and also compute all the ordered partial reductions.

Message Passing Interface (MPI)

Message Passing Interface (MPI) is a standardized and portable message-passing standard. The standard defines the syntax and semantics of a core of library routines useful to a wide range of users writing portable message-passing programs in C, C++, and Fortran.

Processes can be created statically when the program is invoked (e.g. using the mpirun command) or spawned dynamically.

All communications take place within the context of “communication spaces” called communicators, which denote sets of processes, allows the MPI programmer to define modules that encapsulate internal communication structures. A process can belong to many communicators simultaneously. New communicators can be defined dynamically.

Simple send/receives operate with respect to other processes in a communicator. Send must specify a target but receive can wild card on matching sender.

Messages can be tagged with an extra value to aid disambiguation.

Message-passing programming models are by default nondeterministic: the arrival order of messages sent from two processes A and B, to a third process C, is not defined. (However, MPI does guarantee that two messages sent from one process A, to another process B, will arrive in the order sent.)

There are many synchronization modes and a range of collective operations.

MPI Primitives (6 basics functions)

1, int MPI_Init(int *argc, char ***argv): Initiate an MPI computation.

2, int MPI_Finalize(): Terminate a computation.

These must be called once by every participating process, before/after any other MPI calls. They return MPI_SUCCESS if successful, or an error code.

Each process has a unique identifier in each communicator of which it is a member (range 0…members-1). MPI_COMM_WORLD is the built-in global communicator, to which all processes belong by default.

A process can find the size of a communicator, and its own rank within it:

3, int MPI_Comm_Size (MPI_Comm comm, int *np): Determine number of processes (comm - communicator). The processes in a process group are identified with unique, contiguous integers numbered from 0 to np-1.

4, int MPI_Comm_rank (MPI_Comm comm, int *me): Determine my process identifier.

5, MPI_SEND: Send a message.

6, MPI_RECV: Receive a message.

MPI Task Farm

A task farm is bag-of-tasks in which all the tasks are known from the beginning. The challenge is to assign them dynamically to worker processes, to allow for the possibility that some tasks may take much longer to compute than others.

To simplify the code, we assume that there are at least as many tasks as processors and that tasks and results are just integers. In a real application these would be more complex data structures.

Notice the handling of the characteristic non-determinism in the order of task completion, with tags used to identify tasks and results. We also use a special tag to indicate an “end of tasks” message.

/** SPMD style

农场主分配任务给工人 */

#define MAX_TASKS 100

#define NO_MORE_TASKS MAX_TASKS+1

#define FARMER 0 // 第一个 process 是farmer,其余是worker

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int np, rank;

MPI_Init(&argc, &argv);

MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &rank);

MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &np);

if (rank == FARMER) {

farmer(np-1);

} else {

worker();

}

MPI_Finalize();

}

void farmer (int workers) {

int i, task[MAX_TASKS], result[MAX_TASKS], temp, tag, who; MPI_Status status;

// 1, 给每个人发送任务

for (i=0; i<workers; i++) {

MPI_Send(&task[i], 1, MPI_INT, i+1, i, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

}

// 2, 收取任务结果, 继续发放剩余任务

while (i<MAX_TASKS) {

MPI_Recv(&temp, 1, MPI_INT, MPI_ANY_SOURCE, MPI_ANY_TAG, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status);

who = status.MPI_SOURCE; tag = status.MPI_TAG;

result[tag] = temp;

MPI_Send(&task[i], 1, MPI_INT, who, i, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

i++;

}

// 3, 所有任务已经完成, 收集最后一个任务结果, 并且发出结束任务信号

for (i=0; i<workers; i++) {

MPI_Recv(&temp, 1, MPI_INT, MPI_ANY_SOURCE, MPI_ANY_TAG, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status);

who = status.MPI_SOURCE; tag = status.MPI_TAG;

result[tag] = temp;

MPI_Send(&task[i], 1, MPI_INT, who, NO_MORE_TASKS, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

}

}

Notice that the final loop, which gathers the last computed tasks, has a predetermined bound. We know that this loop begins after dispatch of the last uncomputed task, so there must be exactly as many results left to gather as there are workers.

void worker() {

int task, result, tag;

MPI_Status status;

MPI_Recv(&task, 1, MPI_INT, FARMER, MPI_ANY_TAG, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status);

tag = status.MPI_TAG;

while (tag != NO_MORE_TASKS) {

result = somefunction(task);

MPI_Send(&result, 1, MPI_INT, FARMER, tag, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

MPI_Recv(&task, 1, MPI_INT, FARMER, MPI_ANY_TAG, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status);

tag = status.MPI_TAG;

}

}

A worker is only concerned with its interaction with the farmer. 这样速度较快的worker可以自动接更多的任务,最终整体上达成 load balance。

Send in standard mode

int MPI_Send(void *buf, int count, MPI_Datatype datatype, int dest,

int tag, MPI_Comm comm)

Send count items of given type starting in position buf to process dest in communicator comm, tagging the message with tag (which must be non-negative).

There are corresponding datatypes for each basic C type, MPI_INT, MPI_FLOAT etc, and also facilities for constructing derived types which group these together.

Are MPI_Send and MPI_Recv synchronous or asynchronous?

Receive in standard mode

int MPI_Recv(void *buf, int count, MPI_Datatype datatype, int source,

int tag, MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Status *status)

Receive count items of given type starting in position buf, from process source in communicator comm, tagged by tag. It attempts to receive a message that has an envelope corresponding to the specified tag, source, and comm, blocking until such a message is available. When the message arrives, elements of the specified datatype are placed into the buffer at address buf. This buffer is guaranteed to be large enough to contain at least count elements.

Non-determinism (within a communicator) is achieved with “wild cards”, by naming MPI_ANY_SOURCE and/or MPI_ANY_TAG as the source or tag respectively.

A receive can match any available message sent to the receiver which has the specified communicator, tag and source, subject to the constraint that messages sent between any particular pair of processes are guaranteed to appear to be non-overtaking. In other words, a receive cannot match message B in preference to message A if A was sent before B by the same process, the receive will receive the first one which was sent, not the first one to arrive.

The status variable can be used subsequently to inquire about the size, tag, and source of the received message. Status information is returned in a structure with status.MPI_SOURCE and status.MPI_TAG fields. This is useful in conjunction with wild card receives, allowing the receiver to determine the actual source and tag associated with the received message.

Prime Sieve Generator

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

MPI_Comm nextComm; int candidate = 2, N = atoi(argv[1]);

MPI_Init(&argc, &argv);

MPI_Comm_spawn("sieve", argv, 1, MPI_INFO_NULL, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &nextComm, MPI_ERRCODES_IGNORE);

while (candidate<N) {

MPI_Send(&candidate, 1, MPI_INT, 0, 0, nextComm);

candidate++;

}

candidate = -1;

MPI_Send(&candidate, 1, MPI_INT, 0, 0, nextComm);

MPI_Finalize();

}

We use MPI_Comm_spawn to dynamically create new sieve processes as we need them, and MPI_Comm_get_parent to find an inter-communicator to the process group which created us.

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

MPI_Comm predComm, succComm; MPI_Status status;

int myprime, candidate;

int firstoutput = 1; // a C style boolean

MPI_Init (&argc, &argv);

MPI_Comm_get_parent (&predComm);

MPI_Recv(&myprime, 1, MPI_INT, 0, 0, predComm, &status);

printf ("%d is a prime\n", myprime);

MPI_Recv(&candidate, 1, MPI_INT, 0, 0, predComm, &status);

while (candidate!=-1) {

if (candidate%myprime != 0) { // not sieved out

if (firstoutput) { // create my successor if necessary

MPI_Comm_spawn("sieve", argv, 1, MPI_INFO_NULL, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &succComm, MPI_ERRCODES_IGNORE);

firstoutput = 0;

}

MPI_Send(&candidate, 1, MPI_INT, 0, 0, succComm) // pass on the candidate

}

MPI_Recv(&candidate, 1, MPI_INT, 0, 0, predComm, &status); // next candidate

}

if (!firstoutput) MPI_Send(&candidate, 1, MPI_INT, 0, 0, succComm); // candidate=-1, shut down

MPI_Finalize();

}

The message flow is insured by the method in which new processes are spawned/created. Every time a new “sieve” process is spawned, MPI creates it in a new group/communicator. succComm is a handle to this new group which always contains only one process. Therefore, when a candidate is sent to the process, there is only one process in the succComm group and it has id 0.

The Recv function works in the same way predComm is a handle of the parent group (i.e. group of the process that created this sieve). And because the parent was the only process in this group/communicator, it can be identified by id 0.

In conclusion, a process creates at most one successor. This successor is the only process in its group/communicator. The succCom and predComm are handles to the children and parent groups respectively, both of which contain a single process with id 0 which is unique in its own group/communicator.

Spawning New MPI Processes

int MPI_Comm_spawn (char *command, char *argv[], int p, MPI_Info info,

int root, MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Comm *intercomm, int errcodes[])

This spawns p new processes, each executing a copy of program command, in a new communicator returned as intercomm. To the new processes, intercomm appears as MPI_COMM_WORLD. It must be

called by all processes in comm (it is “collective”), with process root computing the parameters. info and errcodes are used in system dependent ways to control/monitor process placement, errors etc.

MPI_Comm_get_parent gives the new processes a reference to the communicator which created them.

Synchronization in MPI

MPI uses the term blocking in a slightly unconventional way, to refer to the relationship between the caller of a communication operation and the implementation of that operation (i.e. nothing to do with any matching operation). Thus, a blocking send complete only when it is safe to reuse the specified output buffer (because the data has been copied somewhere safe by the system). 注意这里跟前面提到的synchronous概念不一样,synchronous 强调接收成功才是判断发送成功与否的标识,而 blocking 只需要保证缓存可以被安全改写即可。

Thus, a blocking send complete only when it is safe to reuse the specified output buffer (because the data has been copied somewhere safe by the system). 注意这里跟前面提到的synchronous概念不一样,synchronous 强调接收成功才是判断发送成功与否的标识,而 blocking 只需要保证缓存可以被安全改写即可。

In contrast, a process calling a non-blocking send continues immediately with unpredictable effects on the value actually sent. Similarly, there is a non-blocking receive operation which allows the calling process to continue immediately, with similar issues concerning the values which appear in the buffer. 意义在于,当需要发送的信息字节非常巨大时,发送和接收耗时都非常久,这时候如果可以不需要等待这些巨量信息的传输而直接继续下一个任务,则能提高效率。

To manage these effects, there are MPI operations for monitoring the progress of non-blocking communications (effectively, to ask, “is it OK to use this variable now?”). - The idea is that with careful use these can allow the process to get on with other useful work even before the user-space buffer has been safely stored.

Blocking Communication Semantics in MPI

MPI provides different blocking send operations, vary in the level of synchronization they provide. Each makes different demands on the underlying communication protocol (i.e. the implementation).

1, Synchronous mode send (MPI_Ssend) is blocking and synchronous, only complete when a matching receive has been found.

2, Standard mode send (MPI_Send) is blocking. Its synchronicity depends upon the state of the implementation buffers, in that it will be asynchronous unless the relevant buffers are full, in which case it will wait for buffer space (and so may appear to behave in a “semi” synchronous fashion).

3, Buffered mode send (MPI_Bsend) is blocking and asynchronous, but the programmer must previously have made enough buffer space available (otherwise an error is reported). There are associated operations for allocating the buffer space.

Receiving with MPI_Recv blocks until a matching message has been completely received into the buffer (so it is blocking and synchronous).

MPI also provides non-blocking sends and receives which return immediately (i.e. possibly before it is safe to use/reuse the buffer). There are immediate versions of all the blocking operations (with an extra “I” in the name). For example, MPI_Isend is the standard mode immediate send, and MPI_Irecv is the immediate receive.

Non-blocking operations have an extra parameter, called a ‘request’ which is a handle on the communication, used with MPI_Wait and MPI_Test to wait or check for completion of the communication (in the sense of the corresponding blocking version of the operation).

Probing for Messages

A receiving process may want to check for a potential receive without actually receiving it. For example, we may not know the incoming message size, and want to create a suitable receiving buffer.

int MPI_Probe(int src, int tag, MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Status *status) behaves like MPI_Recv , filling in *status, without actually receiving the message.

There is also a version which tests whether a message is available immediately int MPI_Iprobe(int src, int tag, MPI_Comm comm, int *flag, MPI_Status *status) leaving a (C-style) boolean result in *flag (i.e. message/no message).

We can then determine the size of the incoming message by inspecting its status information. int MPI_Get_count(MPI_Status *status, MPI_Datatype t, int *count) sets *count to the number of items of type t in message with status *status.

We could use these functions to receive (for example) a message containing an unknown number of integers from an unknown source, but with tag 75, in a given communicator comm.

MPI_Probe(MPI_ANY_SOURCE, 75, comm, &status);

MPI_Get_count(&status, MPI_INT, &count);

buf = (int *) malloc(count*sizeof(int));

source = status.MPI_SOURCE;

MPI_Recv(buf, count, MPI_INT, source, 75, comm, &status);

Collective Operations

MPI offers a range of more complex operations which would otherwise require complex sequences of sends, receives and computations.

These are called collective operations, because they must be called by all processes in a communicator.

1, MPI_Bcast broadcasts count items of type t from buf in root to buf in all other processes in comm:

int MPI_Bcast (void *buf, int count, MPI_Datatype t, int root,

MPI_Comm comm)

2, MPI_Scatter is used to divide the contents of a buffer across all processes.

int MPI_Scatter (void *sendbuf, int sendcount, MPI_Datatype sendt,

void *recvbuf, int recvcount, MPI_Datatype recvt, int root, MPI_Comm comm)

$i^{th}$ chunk (size sendcount) of root’s sendbuf is sent to recvbuf on process $i$ (including the root process itself). The first three parameters are only significant at the root. Counts, types, root and communicator parameters must match between root and all receivers.

3, MPI_Gather is the inverse of MPI_Scatter. Instead of spreading elements from one process to many processes, MPI_Gather takes elements from many processes and gathers them to one single process.

MPI_Gathertakes elements from each process and gathers them to the root process. The elements are ordered by the rank of the process from which they were received. Only therootprocess needs to have a valid receive buffer. Therecv_countparameter is the count of elements received per process, not the total summation of counts from all processes.

MPI_Gather( void* send_data, int send_count, MPI_Datatype send_datatype,

void* recv_data, int recv_count, MPI_Datatype recv_datatype,

int root, MPI_Comm communicator)

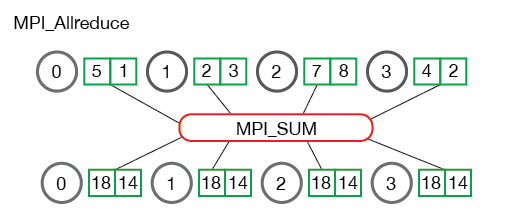

4, MPI_Allreduce computes a reduction, such as adding a collection

of values together. No root, all Processes receive the reduced result.

int MPI_Allreduce (void *sendbuf, void *recvbuf, int count,

MPI_Datatype sendt, MPI_Op op, MPI_Comm comm)

Reduces elements from all send buffers, point-wise, to count single values, using op, storing result(s) in all receive buffers. The op is chosen from a predefined set (MPI_SUM, MPI_MAX etc) or constructed with user code and MPI_Op_create. MPI_Allreduce is the equivalent of doing MPI_Reduce followed by an MPI_Bcast.

Jacobi (1-dimensional wrapped), each neighour is owned by distinct process, thus could not read each other’s data - introduce a layer of message passing, introduce halo as buffer.

// here for convenience MPI_Sendrecv combines a send and a receive.

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &p);

MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &rank);

if (rank == 0) read_problem(&n, work); // 数据存在 root - 0号进程

MPI_Bcast(&n, 1, MPI_INT, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD); // 广播数据

mysize = n/p; // assume p divides n, for simplicity

local = (float *) malloc(sizeof(float) * (mysize+2)); //include fringe/halo

MPI_Scatter(work, mysize, MPI_FLOAT, &local[1], mysize,

MPI_FLOAT, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD); // scatter 分发数据到各process主位置

left = (rank+p-1)%p; // who is my left neighour?

right = (rank+1)%p; // who is my right neighour?

do { //[0]和[mysize+1]halo

MPI_Sendrecv(&local[1], 1, MPI_FLOAT, left, 0, // send this

&local[mysize+1], 1, MPI_FLOAT, right, 0, // receive this

MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status); // anti-clockwise

MPI_Sendrecv(&local[mysize], 1, MPI_FLOAT, right, 0,

&local[0], 1, MPI_FLOAT, left, 0,

MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status); // clockwise

do_one_step(local, &local_error);

MPI_Allreduce(&local_error, &global_error, 1,

MPI_FLOAT, MPI_MAX, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

} while (global_error > acceptable_error);

MPI_Gather (&local[1], mysize, MPI_FLOAT,

work, mysize, MPI_FLOAT, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

if (rank == 0) print_results(n, work);

}

int MPI_Sendrecv(const void *sendbuf, int sendcount, MPI_Datatype sendtype,

int dest, int sendtag,

void *recvbuf, int recvcount, MPI_Datatype recvtype,

int source, int recvtag,

MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Status *status)

Communicators

Communicators define contexts within which groups of processes interact. All processes belong to MPI_COMM_WORLD from the MPI initialisation call onwards.

Create new communicators from old ones by collectively calling

MPI_Comm_split(MPI_Comm old, int colour, int key, MPI_Comm *newcomm) to create new communicators based on colors and keys:

color - control of subset assignment (nonnegative integer). Processes with the same color are in the same new communicator.

key - control of rank assignment (integer).

Within each new communicator, processes are assigned a new rank in the range $0...p^{\prime} − 1$, where $p^{\prime}$ is the size of the new communicator. Ranks are ordered by (but not necessarily equal to) the value passed in as the key parameter, with ties broken by considering process rank in the parent communicator.

This can be helpful in expressing algorithms which contain nested structure. For example, many divide-and-conquer algorithms split the data and machine in half, process recursively within the halves, then unwind to process the recursive results back at the upper level.

//Divide & Conquer Communicators

void some_DC_algorithm ( ..., MPI_Comm comm) {

MPI_Comm_size(comm, &p); MPI_Comm_rank(comm, &myrank);

... pre-recursion work ...

if (p>1) {

MPI_Comm_split (comm, myrank<(p/2), 0, &subcomm); // two sub-machines

some_DC_algorithm (..., subcomm); // recursive step

// in both sub-machines

} else do_base_case_solution_locally();

... post-recursion work ...

}

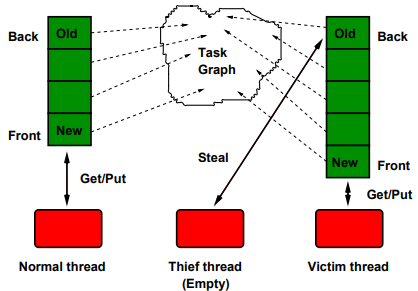

Task and Pattern Based Models

Programming explicitly with threads (or processes) has some drawbacks: • Natural expression of many highly parallel algorithms involves creation of far more threads than there are cores. Thread creation and scheduling have higher overheads than simpler activities like function calls (by a factor of 50-100). • The OS has control over the scheduling of threads to processor cores, but it does not have the application specific knowledge required to make intelligent assignments (for example to optimize cache re-use). Traditional OS concerns for fairness may be irrelevant or even counter-productive.

To avoid this, programmers resort to complex scheduling and synchronization of a smaller number of coarser grained threads. How to avoid this?

A number of languages and libraries have emerged which • separate the responsibility for identifying potential parallelism, which remains the application programmer’s job, from detailed scheduling of this work to threads and cores, which becomes the language/library run-time’s job. • provide abstractions of common patterns of parallelism, which can be specialized with application specific operations, leaving implementation of the pattern and its inherent synchronization to the system.

These are sometimes called task based approaches, in contrast to traditional threaded models. Examples include OpenMP, which is a compiler/language based model, and Intel’s Threading Building Blocks library.

Threading Building Blocks

Threading Building Blocks (TBB) is a shared variable model, C++ template-based library. It uses generic programming techniques to provide a collection of parallel algorithms, each of which is an abstraction of a parallel pattern. It also provides a direct mechanism for specifying task graphs and a collection of concurrent data structures and synchronization primitives.

泛型程序设计(generic programming)是程序设计语言的一种风格或范式,允许程序员在强类型程序设计语言中编写代码时使用一些以后才指定的类型,在实例化时作为参数指明这些类型。

It handles scheduling of tasks, whether explicit programmed or inferred from pattern calls, to a fixed number of threads internally. In effect, this is a hidden Bag-of-Tasks, leaving the OS with almost nothing to do.

Game of Life (cs106b 作业1) Original Code for a Step

enum State {DEAD,ALIVE} ; // cell status

typedef State **Grid;

void NextGen(Grid oldMap, Grid newMap) {

int row, col, ncount;

State current;

for (row = 1; row <= MAXROW; row++) {

for (col = 1; col <= MAXCOL; col++) {

current = oldMap[row][col];

ncount = NeighborCount(oldMap, row, col);

newMap[row][col] = CellStatus(current, ncount);

} } }

TBB parallel_for

假设我们想将上面的函数NextGen应用到数组(网格)的每个元素,这个例子是可以放心使用并行处理模式的。函数模板tbb::parallel_for 将此迭代空间(Range)分解为一个个块,并把每个块运行在不同的线程上。要并行化这个循环,第一步是将循环体转换为可以在一个块上运行的形式 - 一个STL风格的函数对象,称为body对象,其中由operator()中处理。

Game of Life Step Using parallel_for

void NextGen(Grid oldMap, Grid newMap) {

parallel_for (blocked_range<int>(1, maxrow+1), // Range

CompNextGen(oldMap, newMap), // Body

affinity_partitioner()); // Partitioner

}

Range defines a task(iteration) space, and its sub-division (partition) technique; Body defines the code which processes a range; Partitioner (optional parameter) influencing partitioning and scheduling strategy.

The parallel_for Template:

template <typename Range, typename Body>

void parallel_for(const Range& range, const Body &body);

Requires definition of:

- A

rangespace to iterate over- Must define a copy constructor and a destructor

- a destructor to destroy these copies

- Defines

is_empty() - Defines i

s_divisible() - Defines a splitting constructor,

R(R &r, split)

- A

bodytype that operates on the range (or a subrange)- Must define a copy constructor, which is invoked to create a separate copy (or copies) for each worker thread.

- Defines

operator()

In the C++ programming language, a copy constructor is a special constructor for creating a new object as a copy of an existing object.

//通用形式

classname (const classname &obj) {

// body of constructor

}

//实例

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Line {

public:

int getLength( void );

Line( int len ); // simple constructor

Line( const Line &obj); // copy constructor

~Line(); // destructor

private:

int *ptr;

};

Range Class