爱丁堡大学信息学院课程笔记 Software Testing, Informatics, University of Edinburgh

Reference: http://www.inf.ed.ac.uk/teaching/courses/st/2017-18/index.html Pezze and Young, Software Testing and Analysis: Process, Principles and Techniques, Wiley, 2007.

Why Software Testing?

1, 软件的漏洞, 错误和失效 Software Faults, Errors & Failures The problem start with Faults,

Fault(BUG): latent error, mistakes in programming.

e.g add(x, y) = x * y.

With the Faults in programs, if and only if executing add(x, y) = x * y, the fault being activated, and generate an Errors.

Error: An incorrect internal state that is the manifestation of some fault

Now we has an effective Error, if and only if we use the values from add(x, y) = x * y to contribute to the program function (such as, assign it to some variables), then we get the Failure.

Failure : External, observable incorrect behavior with respect to the requirements or other description of the expected behavior.

总结: 软件的漏洞不一定会导致错误, 错误不一定会导致软件失效.

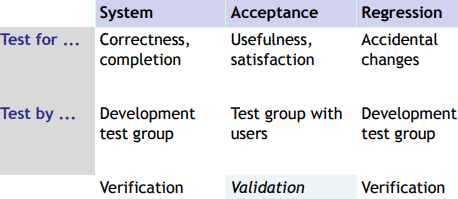

2, 软件工程需要验证确认

在软件项目管理、软件工程及软件测试中,验证及确认(verification and validation,简称V&V)是指检查软件是否匹配规格及其预期目的的程序。验证及确认也被视为一种软件质量管理,是软件开发过程的一部分,一般归类在软件测试中。

Validation: 是否符合预期的目的,是否满足用户实际需求?

Verification: meets the specification?

Verification and Validation (V&V) start at the beginning or even before we decide to build a software product. V&V last far beyond the product delivery as long as the software is in use, to cope with evolution and adaptations to new conditions.

The distinction between the two terms is largely to do with the role of specifications. Validation is the process of checking whether the specification captures the customer’s needs, while verification is the process of checking that the software meets the specification.

3, 软件工程的可靠性 Dependability

In software engineering, dependability is the ability to provide services that can defensibly be trusted within a time-period

Assess the readiness of a product.

Different measures of dependability: • Availability measures the quality of service in terms of running versus down time • Mean time between failures (MTBF) measures the quality of the service in terms of time between failures • Reliability indicates the fraction of all attempted operations that complete successfully

JUnits

JUnit Terminology • A test runner is software that runs tests and reports results. Many implementations: standalone GUI, command line, integrated into IDE • A test suite is a collection of test cases. • A test case tests the response of a single method to a particular set of inputs. • A unit test is a test of the smallest element of code you can sensibly test, usually a single class.

如何使用请参考Java 测试.

Test class

@Before public void init(): Creates a test fixture by creating and initialising objects and values.

@After public void cleanUp(): Releases any system resources used by the test fixture. Java usually does this for free, but files, network connections etc. might not get tidied up automatically.

@Test public void noBadTriangles(), @Test public void scaleneOk(), etc.

These methods contain tests for the Triangle constructor and its isScalene() method.

Test assert

static void assertTrue(boolean test),

static void assertTrue(String message, boolean test),

static void assertFalse(boolean test),

static void assertFalse(String message, boolean test)

软件测试的核心问题和解决思路

A key problem in software testing is selecting and evaluating test cases.

- Test case: A test case is a set of inputs, execution conditions, and a pass/fail criterion.

- Test case specification is a requirement to be satisfied by one or more actual test cases.

- Test suite: a set of test cases.

- Adequacy criterion: a predicate that is true (satisfied) or false (not satisfied) of a < program, test suite > pair.

Adequacy criterion is a set of test obligations, which can be derived from several sources of information, including • specifications (functional and model-based testing) • detailed design and source code (structural testing), • model of system • hypothesized defects (fault-based testing), • security testing.

Test Case Selection and Adequacy Criteria

How do we know when the test suite is enough? It is impossibal to provide adequate test suite for a system to pass. Instead, design rules to highlight inadequacy of test suites: if outcome break the rule, then there is bugs, if not, then not sure…

Test case specification: a requirement to be satisfied by one or more test cases.

Test obligation: a partial test case specification, requiring some property deemed important to thorough testing. From: • Functional (black box specification Functional (black box, specification based): from software specifications • Structural (white or glass box): from code • Model-based: from model of system, models used in specification or design, or derived from code • Fault-based: from hypothesized faults (common bugs)

Adequacy criterion: set of test obligations, a predicate that is true (satisfied) or false (not satisfied) of a (program, test suite) pair.

A test suite satisfies an adequacy criterion if: • all the tests succeed (pass) • every test obligation in the criterion is satisfied by at least one of the test cases in the test suite.

Satisfiability

Sometimes no test suite can satisfy a criterion for a given program, e.g. defensive programming style includes “can’t happen” sanity checks.

Coping with Unsatisfiability: Approach A, exclude any unsatisfiable obligation from the criterion. • Example: modify statement coverage to require execution only of statements that can be executed - But we can’t know for sure which are executable!

Approach B, measure the extent to which a test suite approaches an adequacy criterion • Example: if a test suite satisfies 85 of 100 obligations we have reached 85% coverage.

An adequacy criterion is satisfied or not, a coverage measure is the fraction of satisfied obligations

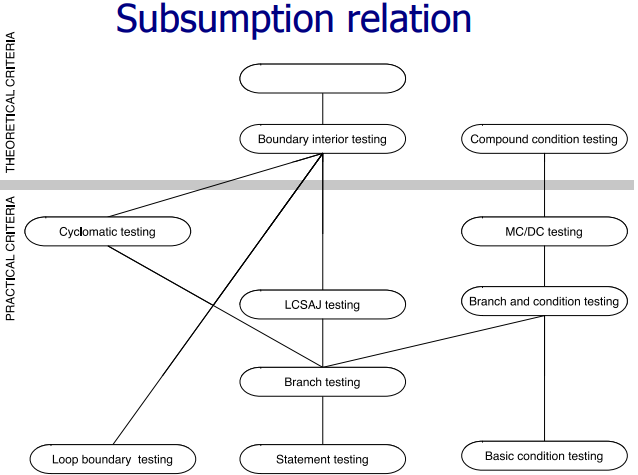

Subsumption relation

Test adequacy criterion A subsumes test adequacy criterion B iff, for every program P, every test suite satisfying A with respect to P also satisfies B with respect to P.

e.g. Exercising all program branches (branch coverage) subsumes exercising all program statements

Functional Testing

Design functional test case: Generate test cases from specifications.

Specification: A functional specification is a description of intended program behavior.

Not based on the internals of the code but program specifications, functional testing is also called specification-based or black-box testing 黑箱測試.

The core of functional test is systematic selection of test cases: partitioning the possible behaviors of the program into a finite number of homogeneous classes, where each such class can reasonably be expected to be consistently correct or incorrect. Test each category and boundaries between (experience suggests failures often lie at the boundaries).

Functional test case design is an indispensable base of a good test suite, complemented but never replaced by structural and fault-based testing, because there are classes of faults that only functional testing effectively detects. Omission of a feature, for example, is unlikely to be revealed by techniques that refer only to the code structure.

Partition Strategies

Failures are sparse in the whole input space, and dense in some specific regions, justified based on specification.

Random (uniform): • Pick possible inputs uniformly • Avoids designer bias: The test designer can make the same logical mistakes and bad assumptions as the program designer (especially if they are the same person) • But treats all inputs as equally valuable

Systematic (non-uniform, Partition Testing Strategies): • Try to select inputs that are especially valuable • Usually by choosing representatives of classes that are apt to fail often or not at all • (Quasi-)Partition: separates the input space into classes whose union is the entire space (classes may overlap), sampling each class in the quasi-partition selects at least one input that leads to a failure, revealing the fault.

Steps of systematic approaches to form test cases from specifications: 1, Decompose the specification. If the specification is large, break it into independently testable features (ITF) to be considered in testing: • An ITF is a functionality that can be tested independently of other functionalities of the software under test. It need not correspond to a unit or subsystem of the software. • ITFs are described by identifying all the inputs that form their execution environments. • ITFs are applied at different granularity levels, from unit testing through integration and system testing. The granularity of an ITF depends on the exposed interface and whichever granularity(unit or system) is being tested. 2, Identify Representative Classes of Values or Derive a Model • Representative values of each input • Representative behaviors of a model: simple input/output transformations don’t describe a system. We use models in program specification, in program design, and in test design 3, Generate Test Case Specifications with constraints: The test case specifications represented by the combinations (cartesian product) of all possible inputs or model behaviors, which must be restricted by ruling out illegal combinations and selecting a practical subset of the legal combinations.

Given a specification, there may be one or more techniques well suited for deriving functional test case. For example, the presence of several constraints on the input domain may suggest using a partitioning method with constraints, such as the category-partition method. While unconstrained combinations of values may suggest a pairwise combinatorial approach. If transitions among a finite set of system states are identifiable in the specification, a finite state machine approach may be indicated.

Combinatorial approaches

Combinatorial approaches to functional testing consist of a manual step of structuring the specification statement into a set of properties or attributes that can be systematically varied and an automatizable step of producing combinations of choices.

总体思路: 1, Identify distinct attributes that can be varied: the data, environment, or configuration 2, Systematically generate combinations to be tested

Rational: test cases should be varied and include possible “corner cases”

Environment describes external factors we need to configure in particular ways in order to specify and execute tests to fully exercise the system. Some common options: System memory, Locale.

There are three main techniques that are successfully used in industrial environments and represent modern approaches to systematically derive test cases from natural language specifications: • category-partition approach to identifying attributes, relevant values, and possible combinations; • Pairwise (n-way) combination test a large number of potential interactions of attributes with a relatively small number of inputs; • provision of catalogs to systematize the manual aspects of combinatorial testing.

Combinatorial approaches 将test cases的粗暴合成分解成一个个步骤,通过解析和综合那些可以量化和监控(并得到工具部分支持)的活动来逐步拆解问题.

A combinatorial approach may work well for functional units characterized by a large number of relatively independent inputs, but may be less effective for functional units characterized by complex interrelations among inputs.

Category-partition 和 pairwise partition 都是使用上面的总体思路,差别在于最后如何自动生成 test cases。

Category-partition

将穷举枚举作为自动生成combinations的基本方法,同时允许测试设计者添加限制组合数量增长的约束条件。当这些约束能够反映应用域中的真实约束(例如,category-partition中的"error"条目)时,能够非常有效地消除许多冗余组合。

- Decompose the specification into independently testable features

- for each feature: identify parameters, environment elements

- for each parameter and environment element: identify elementary characteristics (categories)

- Identify relevant/representative values: for each category identify representative (classes of) values

- normal values

- boundary values

- select extreme values within a class ((e.g., maximum and minimum legal values)

- select values outside but as close as possible to the class

- select interior (non-extreme) values of the class

- special values: 0 and 1, might cause unanticipated behavior alone or in combination with particular values of other parameters.

- error values: values outside the normal domain of the program

- Ignore interactions among values for different categories (considered in the next step)

- Introduce constraints: rule out invalid combinations. For single consgtraints, indicates a value class that test designers choose to test only once to reduce the number of test cases.

优点:Category partition testing gave us systematic approach -Identify characteristics and values (the creative step), generate combinations (the mechanical step).

缺点:test suite size grows very rapidly with number of categories.

不适合使用Category partition testing的情况:当缺乏应用领域的实际约束时,测试设计者为了减少组合数量被迫任意添加的约束(例如,“single"条目),此时不能很有效的减少组合数量。

Pairwise combination testing

Most failures are triggered by single values or combinations of a few values.

为n个测试类选择组合时,除了简单地枚举所有可能的组合外,更实际的组合方案是在集合n中取出k(k<n)项, 一般是二元组或三元组,总的 test cases 要包含所有 features 的两两(或三三)组合。生成测试用例时,先控制某一个变量逐一改变,记录配对了的变量,后续遇到重复的就可以忽略。这样即使没有加constraints也可以大大减少组合数(但我们也可以加constraints)。

使用低阶组合构建测试用例时,可能会遗漏某些高阶组合的情况。

Befinits of functional testing

Functional testing is the base-line technique for designing test cases: • Timely: Often useful in refining specifications and assessing testability before code is written • Effective: finds some classes of fault (e.g.,missing logic) that can elude other approaches • Widely applicable: to any description of program behavior serving as spec, at any level of granularity from module to system testing. • Economical: typically less expensive to design and execute than structural (code-based) test cases

Early functional testing design: • Program code is not necessary: Only a description of intended behavior is needed • Often reveals ambiguities and inconsistency in spec • Useful for assessing testability, and improving test schedule and budget by improving spec • Useful explanation of specification, or in the extreme case (as in Extreme Programming), test cases are the spec

Finite Models

建模主要解决两个工程问题: • 首先,不能等到实际的产品出来后才分析和测试。 • 其次,对实际产品进行彻底的测试是不切实际的,无论是否受制于所有可能的状态和输入。

模型允许我们在开发早期就着手分析,并随着设计的发展重复分析,并允许我们应用比实际情况更广泛的分析方法。更重要的是,这些分析很多都是可以自动化的。

Model program execution, emphasized control.

A model is a representation that is simpler than the artifact it represents but preserves (or at least approximates) some important attributes of the actual artifact.

A good model is: • compact: A model must be representable and manipulable in a reasonably compact form. • Predictive: well enough to distinguish between “good” and “bad” outcomes of analysis. • Semantically meaningful: interpret analysis results in a way that permits diagnosis of the causes of failure. • Sufficiently general: Models intended for analysis of some important characteristic must be general enough for practical use in the intended domain of application.

模型的表达:使用有向图描述程序模型。通常我们将它们绘制为"方框和箭头"图,由一组节点N的组成的集合和它们间的关系E(即ordered pairs的集合),edges。节点表示某种类型的实体,例如源代码的步骤,类或区域。边表示实体之间的某种关系。

模拟程序执行的模型,是该程序状态空间的抽象。通过抽象函数,程序运行状态空间中的状态与程序运行的finite state 模型中的状态相关联。但抽象函数无法完美呈现程序运行的所有细节,将实际的无限可能的状态折叠成有限必然需要省略一些信息,这就引入了不确定性nondeterminism。

有什么软件模型的基本概念,又有哪些可以应用于测试和分析的模型?

Controal flow graph

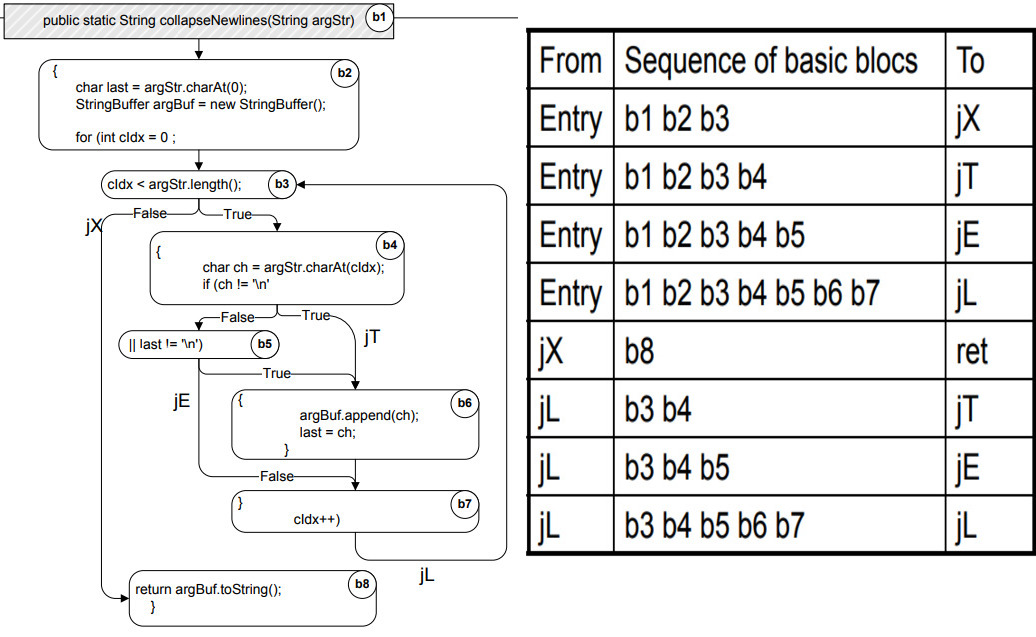

程序中的单个步骤或方法的 Control flow 可以用 过程内流程图 intraprocedural control flow graph (CFG) 来表示. CFG 模拟通过单个过程或方法的可能运行路径, 是一个有向图,nodes 表示源代码的一个个区域,有向边 directed edges 表示程序可以在哪些代码区域间流转.

public static String collapseNewlines(String argStr) {

char last = argStr.charAt(0);

StringBuffer argBuf = new StringBuffer();

for (int cIdx = 0 ; cIdx < argStr.length(); cIdx++) {

char ch = argStr.charAt(cIdx);

if (ch != '\n' || last != '\n') {

argBuf.append(ch);

last = ch;

}

}

return argBuf.toString();

}

左边是上面代码对应的CFG,右边的表格是Linear Code Sequence and Jump (LCSJ),表示从一个分支到另一个分支的控制流程图的子路径

Nodes = regions of source code (basic blocks) • Basic block = maximal program region with a single entry and single exit point • Often statements are grouped in single regions to get a compact model • Sometime single statements are broken into more than one node to model control flow within the statement Directed edges = possibility that program execution proceeds from the end of one region directly to the beginning of another

为了便于分析,控制流程图通常会通过其他信息进一步加持。例如,后面介绍的数据流模型 data flow models 就是基于加持了有关变量被程序各个语句访问和修改的信息的CFG模型构建的.

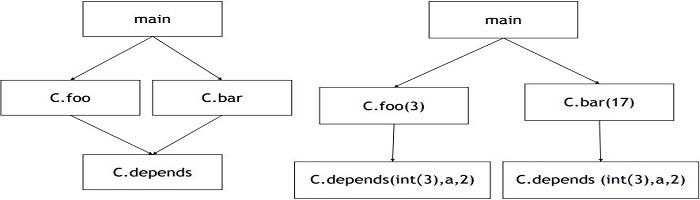

Call Graphs

过程间流程 Interprocedural control flow 也可以表示为有向图。最基本的模型是调用图 call graphs, nodes represent procedures (methods, C functions, etc.) and edges represent the “calls” relation.

相较于CFG,调用图比有更多设计问题和权衡妥协, 因此基本调用图的表达方式是不固定的,特别是在面向对象的语言中,methods跟对象动态绑定。

调用图存在Overapproximation现象,比如尽管方法A.check()永远不会实际调用C.foo(),但是一个典型的调用图会认为这个调用是可能的。

Context-sensitive call graph:调用图模型根据过程被调用的具体位置来表示不同行为。

public class Context {

public static void main(String args[]) {

Context c = new Context();

c.foo(3);

c.bar(17);

}

void foo(int n) {

int[] myArray = new int[ n ];

depends( myArray, 2) ;

}

void bar(int n) {

int[] myArray = new int[ n ];

depends( myArray, 16) ;

}

void depends( int[] a, int n ) {

a[n] = 42;

}

}

Context sensitive analyses can be more precise than Context-insensitive analyses when the model includes some additional information that is shared or passed among procedures. But sensitive call graphs size grows exponentially, not fit for large program.

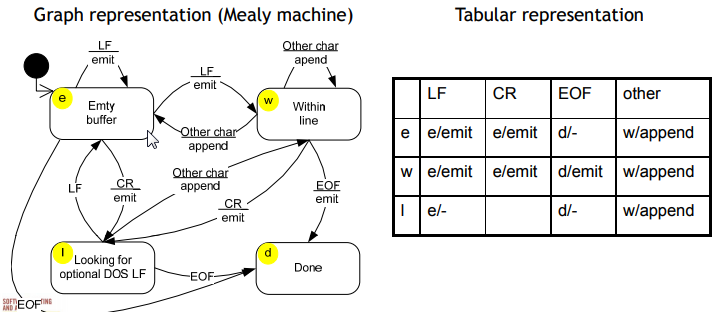

Finite state machines

前面介绍的模型都是都是基于源代码抽象出来的。不过,模型的构建也常常先于或者独立于源代码,有限状态机 finite state machines 就是这种模型。

有限状态机(finite-state machine,FSM)又称有限状态自动机,简称状态机,是表示有限个状态以及在这些状态之间的转移和动作等行为的数学模型。

最简单的FSM由一个有限的状态集合和状态间的转移动作构成,可以有向图表示,节点表示状态,edges表示在状态间的转移需要的运算、条件或者事件。因为可能存在无限多的程序状态,所以状态节点的有限集合必须是具体编程状态的抽象。

Usually we label the edge to indicate a program operation, condition, or event associated with the transition. We may label transitions with both an external event or a condition and with a program operation that can be thought of as a “response” to the event. Such a finite state machine with event/response labels on transitions is called a Mealy machine.

In the theory of computation, a Mealy machine is a finite-state machine whose output values are determined both by its current state and the current inputs. (This is in contrast to a Moore machine, whose output values are determined solely by its current state.)

An alternative representation of finite state machines, including Mealy machines, is the state transition table:

There is one row in the transition table for each state node and one column for each event or input. If the FSM is complete and deterministic, there should be exactly one transition in each table entry. Since this table is for a Mealy machine, the transition in each table entry indicates both the next state and the response (e.g., d / emit means “emit and then proceed to state d”).

There is one row in the transition table for each state node and one column for each event or input. If the FSM is complete and deterministic, there should be exactly one transition in each table entry. Since this table is for a Mealy machine, the transition in each table entry indicates both the next state and the response (e.g., d / emit means “emit and then proceed to state d”).

Structural Testing

Judging test suite thoroughness based on the structure of the program itself, it is still testing product functionality against its specification, but the measure of thoroughness has changed to structural criteria. Also known as “white-box”, “glass-box”, or “codebased” testing.

Motivation: 1, If part of a program is not executed by any test case in the suite, faults in that part cannot be exposed. The part is a control flow element or combination, statements (or CFG nodes), branches (or CFG edges), fragments and combinations, conditions paths. 2, Complements functional testing, another way to recognize cases that are treated differently 3, Executing all control flow elements does not guarantee finding all faults: Execution of a faulty statement may not always result in a failure • The state may not be corrupted when the statement is executed with some data values • Corrupt state may not propagate through execution to eventually lead to failure 4, Structural coverage: Increases confidence in thoroughness of testing, removes some obvious inadequacies

Steps:

- Create functional test suite first, then measure structural coverage to identify see what is missing

- Interpret unexecuted elements

- may be due to natural differences between specification and implementation

- or may reveal flaws of the software or its development process

- inadequacy of specifications that do not include cases present in the implementation

- coding practice that radically diverges from the specification

- inadequate functional test suites

Coverage measurements are convenient progress indicators, sometimes used as a criterion of completion.

Control-flow Adequacy (expression coverage)

A structural testing strategy that uses the program’s control flow as a model. Control flow elements include statements, branches, conditions, and paths.

But a set of correct program executions in which all control flow elements are exercised does not guarantee the absence of faults.

Test based on control-flow are concerned with expression coverage.

Statement testing

Adequacy criterion: each statement (or node in the CFG) must be executed at least once. Because a fault in a statement can only be revealed by executing the faulty statement.

Coverage: #(executed statements) / #(statements)

Minimizing test suite size is seldom the goal, but small test cases make failure diagnosis easier.

Complete statement coverage may not imply executing all branches in a program.

Branch testing

Adequacy criterion: each branch (edge in the CFG) must be executed at least once.

Coverage: #(executed branches) / #(branches)

Traversing all edges of a graph causes all nodes to be visited: test suites that satisfy the branch adequacy criterion for a program P also satisfy the statement adequacy criterion for the same program

But “All branches” can still miss conditions.

Sample fault: missing operator (negation):digit_high == 1 || digit_low == -1, branch adequacy criterion can be satisfied by varying only part of the condition.

Condition testing

Basic condition adequacy criterion: each basic condition must be executed at least once.

Coverage: #(truth values taken by all basic conditions) / 2 * #(basic conditions)

Branch and basic condition are not comparable. Basic condition adequacy criterion can be satisfied without satisfying branch coverage

Branch and condition adequacy: cover all conditions and all decisions

Compound condition adequacy:

• Cover all possible evaluations of compound conditions - A compound condition is either an atomic condition or some boolean formula of atomic conditions. For example, in the overall condition “A || (B && C)” the set of compound conditions are “A”, “B”, “C", "B && C”, “A || (B && C)”.

• Cover all branches of a decision tree.

• Number of test cases grows exponentially with the number of basic conditions in a decision ($2^N$).

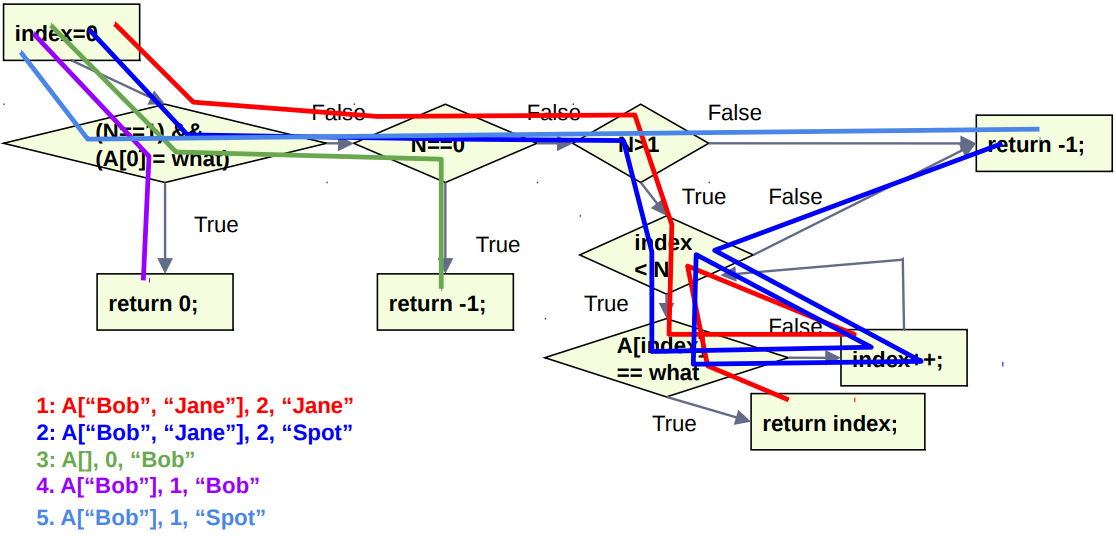

练习 - Write tests that provide statement, branch, and basic condition coverage over the following code:

int search(string A[], int N, string what){

int index = 0;

if ((N == 1) && (A[0] == what)){

return 0;

} else if (N == 0){

return -1;

} else if (N > 1){

while(index < N){

if (A[index] == what) return index;

else index++;

}

}

return -1;

}

先画出 CFG 图,再遍历:

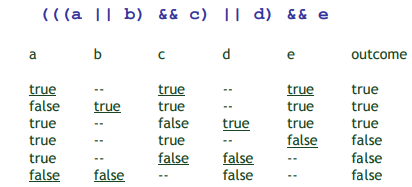

Modified condition/decision adequacy criterion (MC/DC)

Motivation: Effectively test important combinations of conditions, without exponential blow up in test suite size. (Important combinations: Each basic condition shown to independently affect the outcome of each decision)

假如这些组合表明每一个条件都可以独立影响结果,那么就不要穷尽各种条件组合了,对于那些不影响结果的条件组合,测了也没有意义。

Requires:

• For each basic condition $C_i$, two test cases

• 控制变量,只改变 $C_i$:values of all evaluated conditions except $C_i$ are the same

• Compound condition as a whole evaluates to True for one and False for the other,结果的改变表明 $C_i$ 可以独立影响结果

MC/DC: • basic condition coverage (C) • branch coverage (DC) • plus one additional condition (M): every condition must independently affect the decision’s output

It is subsumed by compound conditions and subsumes all other criteria discussed so far - stronger than statement and branch coverage. A good balance of thoroughness and test size (and therefore widely used).

Path Testing

Sometimes, a fault is revealed only through exercise of some sequence of decisions (i.e., a particular path through the program).

Path coverage requires that all paths through the CFG are covered. In theory, path coverage is the ultimate coverage metric. But in practice, it is impractical if there is loop involed.

Adequacy criterion: each path must be executed at least once: Coverage = #(Paths Covered) / #(Total Paths)

Practical path coverage criteria: • The number of paths in a program with loops is unbounded - the simple criterion is usually impossible to satisfy • For a feasible criterion: Partition infinite set of paths into a finite number of classes • Useful criteria can be obtained by limiting •• the number of traversals of loops •• the length of the paths to be traversed •• the dependencies among selected paths

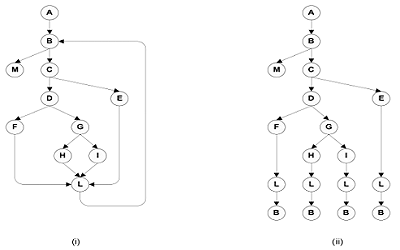

Boundary Interior Coverage

Groups paths that differ only in the subpath they follow when repeating the body of a loop.

• Follow each path in the control flow graph up to the first repeated node

• The set of paths from the root of the tree to each leaf is the required set of subpaths for boundary/interior coverage

把分支拆分为每一条可能的 path.

把分支拆分为每一条可能的 path.

Limitations: 1, The number of paths through non-loop branches (conditions) can still be exponential ($2^N$). 2, Choosing input data to force execution of one particular path may be very difficult, or even impossible if the conditions are not independent.

Loop Boundary Coverage

Since coverage of non-looping paths is expensive, we can consider a variant of the boundary/interior criterion that treats loop boundaries similarly but is less stringent with respect to other differences among paths.

Criterion: A test suite satisfies the loop boundary adequacy criterion iff for every loop: • In at least one test case, the loop body is iterated zero times • In at least one test case, the loop body is iterated once • In at least one test case, the loop body is iterated more than once

For simple loops, write tests that:

- Skip the loop entirely.

- Take exactly one pass through the loop.

- Take two or more passes through the loop.

- (optional) Choose an upper bound N, and:

- M passes, where 2 < M < N

- (N-1), N, and (N+1) passes

For Nested Loops:

- For each level, you should execute similar strategies to simple loops.

- In addition:

- Test innermost loop first with outer loops executed minimum number of times.

- Move one loops out, keep the inner loop at “typical” iteration numbers, and test this layer as you did the previous layer.

- Continue until the outermost loop tested.

For Concatenated Loops, one loop executes. The next line of code starts a new loop:

- These are generally independent(Most of the time…)

- If not, follow a similar strategy to nested loops.

- Start with bottom loop, hold higher loops at minimal iteration numbers.

- Work up towards the top, holding lower loops at “typical” iteration numbers.

Linear Code Sequences and Jumps

There are additional path-oriented coverage criteria that do not explicitly consider loops. Among these are criteria that consider paths up to a fixed length. The most common such criteria are based on Linear Code Sequence and Jump (LCSAJ) - sequential subpath in the CFG starting and ending in a branch.

A single LCSAJ is a set of statements that come one after another (meaning no jumps) followed by a single jump. A LCSAJ starts at either the beginning of the function or at a point that can be jumped to. The LCSAJ coverage is what fraction of all LCSAJs in a unit are followed by your test suite.

We can require coverage of all sequences of LCSAJs of length N. Stronger criteria can be defined by requiring N consecutive LCSAJs to be covered - $TER_{N+2}$: 1, $TER_1$ is equivalent to statement coverage. 2, $TER_2$ is equivalent to branch coverage 3, $TER_3$ is LCSAJ coverage 4, $TER_4$ is how many pairs of LCSAJ covered …

Cyclomatic adequacy (Complexity coverage)

There are many options for the set of basis subpaths. When testing, count the number of independent paths that have already been covered, and add any new subpaths covered by the new test.

You can identify allpaths with a set of independent subpaths of size = the cyclomatic complexity. Cyclomatic coverage counts the number of independent paths that have been exercised, relative to cyclomatic complexity.

• A path is representable as a bit vector, where each component of the vector represents an edge • “Dependence” is ordinary linear dependence between (bit) vectors

If e = #(edges), n = #(nodes), c = #(connected components) of a graph, it is $e - n + c$ for an arbitrary graph, $e - n + 2$ for a CFG.

Cyclomatic Complexity could be used to guess “how much testing is enough”. ○ Upper bound on number of tests for branch coverage. ○ Lower bound on number of tests for path coverage.

And Used to refactor code. ○ Components with a complexity > some threshold should be split into smaller modules. ○ Based on the belief that more complex code is more fault-prone.

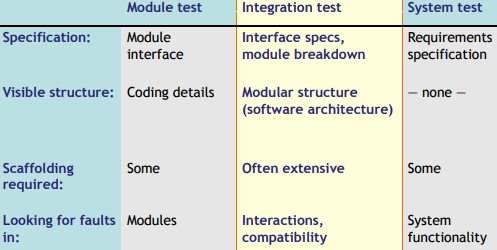

Procedure call coverage

The criteria considered to this point measure coverage of control flow within individual procedures - not well suited to integration or system testing, where connections between procedures(calls and returns) should be covered.

Choose a coverage granularity commensurate with the granularity of testing - if unit testing has been effective, then faults that remain to be found in integration testing will be primarily interface faults, and testing effort should focus on interfaces between units rather than their internal details.

Procedure Entry and Exit Testing - A single procedure may have several entry and exit points. • In languages with goto statements, labels allow multiple entry points. • Multiple returns mean multiple exit points.

Call coverage: The same entry point may be called from many points. Call coverage requires that a test suite executes all possible method calls.

Satisfying structural criteria

The criterion requires execution of

The criterion requires execution of

- statements that cannot be executed as a result of:

- defensive programming

- code reuse (reusing code that is more general than strictly required for the application)

- conditions that cannot be satisfied as a result of interdependent conditions

- paths that cannot be executed as a result of interdependent decisions

Rather than requiring full adequacy, the “degree of adequacy” of a test suite is estimated by coverage measures.

Dependence and Data Flow Models

前面介绍的 Finite models (Control flow graph, call graph, finite state machines) 只是捕捉程序各部分之间依赖关系的其中一个方面。它们明确地表现控制流程,但不重视程序变量间的信息传递. Data flow models provide a complementary view, emphasizing and making explicit relations involving transmission of information.

Models of data flow and dependence in software were originally developed in the field of compiler construction, where they were (and still are) used to detect opportunities for optimization.

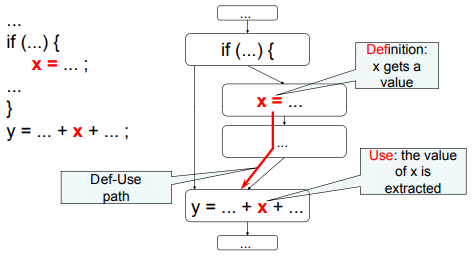

Definition-Use Pairs (Def-Use Pairs)

The most fundamental class of data flow model associates the point in a program where a value is produced (called a “definition”) with the points at which the value may be accessed (called a “use”).

Definitions - Variable declaration (often the special value “uninitialized”), Variable initialization, Assignment, Values received by a parameter.

Use - Expressions, Conditional statements, Parameter passing, Returns.

A Definition-Use pair is formed if and only if there is a definition-clear path between the Definition and the Use. A definition-clear path is a path along the CFG path from a definition to a use of the same variable without another definition of the variable in between.

<D,U> pairs coverage: #(pairs covered)/ #(total number of pairs)

If instead another definition is present on the path, then the latter definition kills the former.

Definition-use pairs record direct data dependence, which can be represented in the form of a graph - (Direct) Data Dependence Graph, with a directed edge for each definition-use pair.

The notion of dominators in a rooted, directed graph can be used to make this intuitive notion of “controlling decision” precise. Node M dominates node N if every path from the root of the graph to N passes through M.

Analyses: Reaching definition

Definition-use pairs can be defined in terms of paths in the program control flow graph. • There is an association $(d,u)$ between a definition of variable $v$ at $d$ and a use of variable $v$ at $u$ if and only if there is at least one control flow path from $d$ to $u$ with no intervening definition of $v$. • Definition $v_d$ reaches $u$ ($v_d$ is a reaching definition at $u$). • If a control flow path passes through another definition $e$ of the same variable $v$, we say that $v_e$ kills $v_d$ at that point.

Practical algorithms do not search every individual path. Instead, they summarize the reaching definitions at a node over all the paths reaching that node.

An algorithm for computing reaching definitions is based on the way reaching definitions at one node are related to reaching definitions at an adjacent node.

Suppose we are calculating the reaching definitions of node n, and there is an edge $(p,n)$ from an immediate predecessor node $p$. We observe: • If the predecessor node $p$ can assign a value to variable $v$, then the definition $v_p$ reaches $n$. We say the definition $v_p$ is generated at $p$. • If a definition $v_d$ of variable $v$ reaches a predecessor node $p$, and if $v$ is not redefined at that node, then the definition is propagated on from $p$ to $n$.

These observations can be stated in the form of an equation describing sets of reaching definitions.

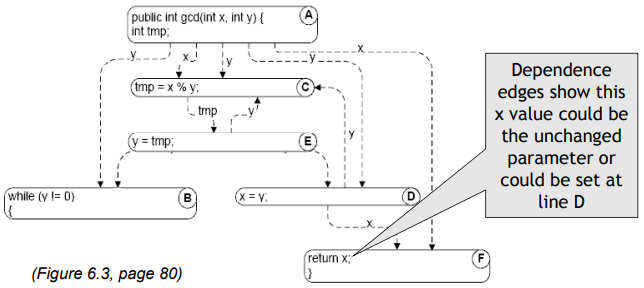

/** Euclid's algorithm */

public class GCD {

public int gcd(int x, int y) {

int tmp; // A: def x, y, tmp

while (y != 0) { // B: use y

tmp = x % y; // C: def tmp; use x, y

x = y; // D: def x; use y

y = tmp; // E: def y; use tmp

}

return x; // F: use x

}

}

Reaching definitions at node E are those at node D, except that D adds a definition of x and replaces (kills) an earlier definition of x:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} Reach(E) &= ReachOut(D) \\\\ ReachOut(D) &= (Reach(D) \backslash \{x_A\}) \cup \{x_D\} \end{split} \end{equation} $$Equations at the head of the while loop - node B, where values may be transmitted both from the beginning of the procedure - node A and through the end of the body of the loop - node E. The beginning of the procedure (node A) is treated as an initial definition of parameters and local variables:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} Reach(B) &= ReachOut(A) \cup ReachOut(E) \\\\ ReachOut(A) &= gen(A) = \{x_A, y_A, tmp_A \} \\\\ ReachOut(E) &= (Reach(E) \backslash \{y_A\}) \cup \{y_D\} \end{split} \end{equation} $$(If a local variable is declared but not initialized, it is treated as a definition to the special value “uninitialized.”)

General equations for Reach analysis:

$$\begin{equation} \begin{split} Reach(n) &= \mathop{\cup} \limits_{m \in pred(n)} ReachOut(m) \\\\ ReachOut(n) &=(Reach(n) \backslash kill(n)) \cup gen(n) \\\\ \end{split} \end{equation}$$$gen(n) = v_n$, $v$ is defined or modified at $n$; $kill(n) = v_x$, $v$ is defined or modified at $x, x \ne n$.

Reaching definitions calculation: first initializing the reaching definitions at each node in the control flow graph to the empty set, and then applying these equations repeatedly until the results stabilize.

Analyses: Live and Avail

Available expressions is another classical data flow analysis, used in compiler construction to determine when the value of a subexpression can be saved and reused rather than recomputed.

An expression is available at a point if, for all paths through the control flow graph from procedure entry to that point, the expression has been computed and not subsequently modified.

An expression is generated (becomes available) where it is computed and is killed (ceases to be available) when the value of any part of it changes (e.g., when a new value is assigned to a variable in the expression).

The expressions propagation to a node from its predecessors is described by a pair of set equations:

$$\begin{equation} \begin{split} Avail(n) &= \mathop{\cap} \limits_{m \in pred(n)} AvailOut(m) \\\\ AvailOut(n) &=(Avail(n) \backslash kill(n)) \cup gen(n) \\\\ \end{split} \end{equation}$$$gen(n)$, available, computed at $n$; $kill(n)$, has variables assigned at $n$.

Reaching definitions combines propagated sets using set union, since a definition can reach a use along any execution path. Available expressions combines propagated sets using set intersection, since an expression is considered available at a node only if it reaches that node along all possible execution paths.

Reaching definitions is a forward, any-path analysis; Available expressions is a forward, all-paths analysis.

Live variables is a backward, any-path analysis that determines whether the value held in a variable may be subsequently used. Backward analyses are useful for determining what happens after an event of interest.

A variable is live at a point in the control flow graph if, on some execution path, its current value may be used before it is changed, i.e. there is any possible execution path on which it is used.

$$\begin{equation} \begin{split} Live(n) &= \mathop{\cup} \limits_{m \in succ(n)} LiveOut(m) \\\\ LiveOut(n) &=(Live(n) \backslash kill(n)) \cup gen(n) \\ \end{split} \end{equation}$$$gen(n)$, $v$ is used at $n$; $kill(n)$, $v$ is modified at $n$.

One application of live variables analysis is to recognize useless definitions, that is, assigning a value that can never be used.

Iterative Solution of Dataflow Equations

Initialize values (first estimate of answer) • For “any path” problems, first guess is “nothing”(empty set) at each node • For “all paths” problems, first guess is “everything” (set of all possible values = union of all “gen” sets)

Repeat until nothing changes • Pick some node and recalculate (new estimate)

From Execution to Conservative Flow Analysis

We can use the same data flow algorithms to approximate other dynamic properties • Gen set will be “facts that become true here” • Kill set will be “facts that are no longer true here” • Flow equations will describe propagation

Example: Taintedness (in web form processing) • “Taint”: a user-supplied value (e.g., from web form) that has not been validated • Gen: we get this value from an untrusted source here • Kill: we validated to make sure the value is proper

Data flow analysis with arrays and pointers

The models and flow analyses described in the preceding section have been limited to simple scalar variables in individual procedures.

Arrays and pointers (dynamic references and the potential for aliasing) introduce uncertainty: Do different expressions access the same storage? • a[i] same as a[k] when i = k • a[i] same as b[i] when a = b (aliasing)

The uncertainty is accomodated depending on the kind of analysis • Any-path: gen sets should include all potential aliases and kill set should include only what is definitely modified • All path: vice versa

Scope of Data Flow Analysis

过程内 Intraprocedural: Within a single method or procedure, as described so far.

过程之间 Interprocedural: Across several methods (and classes) or procedures

Cost/Precision trade-offs for interprocedural analysis are critical, and difficult: context sensitivity, flow-sensitivity.

Many interprocedural flow analyses are flow-insensitive • $O(n^3)$ would not be acceptable for all the statements in a program. Though $O(n^3)$ on each individual procedure might be ok • Often flow-insensitive analysis is good enough… considering type checking as an example

Reach, Avail, etc were flow-sensitive sensitive, intraprocedural analyses. • They considered ordering and control flow decisions • Within a single procedure or method, this is (fairly) cheap - $O(n^3)$ for $n$ CFG nodes.

Summary of Data flow models

- Data flow models detect patterns on CFGs:

- Nodes initiating the pattern

- Nodes terminating it

- Nodes that may interrupt it

- Often, but not always, about flow of information (dependence)

- Pros:

- Can be impy g lemented by efficient iterative algorithms

- Widely applicable (not just for classic “data flow” properties)

- Limitations:

- Unable to distinguish feasible from infeasible paths

- Analyses spanning whole programs (e.g., alias analysis) must trade off precision against computational cost

Data Flow Testing

In structural testing, • Node and edge coverage don’t test interactions • Path-based criteria require impractical number of test cases: And only a few paths uncover additional faults, anyway • Need to distinguish “important” paths

Data flow testing attempts to distinguish “important” paths: Interactions between statements - Intermediate between simple statement and branch coverage and more expensive path-based structural testing.

Intuition: Statements interact through data flow • Value computed in one statement used in another Value computed in one statement, used in another • Bad value computation revealed only when it is used

Adequacy criteria: • All DU pairs: Each DU pair is exercised by at least one test case • All DU paths: Each simple (non looping) DU path is exercised by at least one test case • All definitions: For each definition, there is at least one test case which exercises a DU pair containing it - Every computed value is used somewhere

Limits: Aliases, infeasible paths - Worst case is bad (undecidable properties, exponential blowup of paths), so 务实的 pragmatic compromises are required

Data flow coverage with complex structures

Arrays and pointers • Under-estimation of aliases may fail to include some DU pairs • Over-estimation, may introduce unfeasible test obligations

For testing, it may be preferrable to accept under-estimation of alias set rather than over-estimation or expensive analysis • 有争议的 Controversial: In other applications (e.g., compilers), a conservative over-estimation of aliases is usually required • Alias analysis may rely on external guidance or other global analysis to calculate good estimates • Undisciplined use of dynamic storage, pointer arithmetic, etc. may make the whole analysis infeasible

Mutation testing

Fault-based Testing, directed towards “typical” faults that could occur in a program.

- Take a program and test suite generated for that program (using other test techniques)

- Create a number of similar programs (mutants), each differing from the original in one small way, i.e., each possessing a fault

- The original test data are then run through the mutants

- Then mutants either:

- To be dead: test data detect all differences in mutants, the test set is adequate.

- Remains live if:

- it is equivalent to the original program (functionally identical although syntactically different - called an equivalent mutant) or,

- the test set is inadequate to kill the mutant. The test data need to be augmented (by adding one or more new test cases) to kill the live mutant.

Numbers of mutants tend to be large (the number of mutation operators is large as they are supposed to capture all possible syntactic variations in a program), hence random sampling, selective mutation operators (Offutt).

Coverage - mutation score: #(killed mutants) / #(all non-equivalent mutants) (or random sample).

Benifits: • It provides the tester with a clear target (mutants to kill) • It does force the programmer to think of the test data that will expose certain kinds of faults • Probably most useful at unit testing level

Mutation operators could be built on • source code (body), • module interfaces (aimed at integration testing), • specifications: Petri-nets, state machines, (aimed at system testing)

Tools: MuClipse

Model based testing

Models used in specification or design have structure • Useful information for selecting representative classes of behavior; behaviors that are treated differently with respect to the model should be tried by a thorough test suite • In combinatorial testing, it is difficult to capture that structure clearly and correctly in constraints

Devise test cases to check actual behavior against behavior specified by the model - “Coverage” similar to structural testing, but applied to specification and design models.

Deriving test cases from finite state machines: From an informal specification, to a finite state machine, to a test suite

“Covering” finite state machines • State coverage: Every state in the model should be visited by at least one test case • Transition coverage •• Every transition between states should be traversed by at least one test case. •• A transition can be thought of as a (precondition, postcondition) pair.

Models are useful abstractions • In specification and design, they help us think and communicate about complex artifacts by emphasizing key features and suppressing details • Models convey structure and help us focus on one thing at a time

We can use them in systematic testing • If a model divides behavior into classes, we probably want to exercise each of those classes! • Common model-based testing techniques are based on state machines, decision structures, and grammars, but we can apply the same approach to other models.

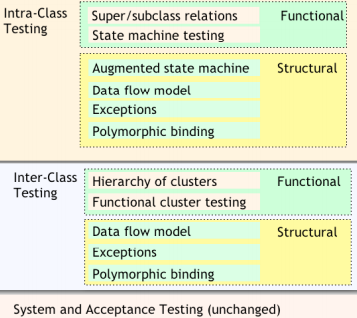

Testing Object Oriented Software

Typical OO software characteristics that impact testing • State dependent behavior • Encapsulation • Inheritance • 多态性 Polymorphism and dynamic binding • Abstract and generic classes • Exception handling

Procedural software, unit = single program, function, or procedure, more often: a unit of work that may correspond to one or more intertwined functions or programs.

Object oriented software: • unit = class or (small) cluster of strongly related classes (e.g., sets of Java classes that correspond to exceptions) • unit testing = 类内测试 intra-class testing • integration testing = 类之间测试 inter-class testing (cluster of classes) • dealing with single methods separately is usually too expensive (complex scaffolding), so methods are usually tested in the context of the class they belong to.

Basic approach is orthogonal: Techniques for each major issue (e.g., exception handling, generics, inheritance ) can be applied incrementally and independently.

Intraclass State Machine Testing

Basic idea: • The state of an object is modified by operations • Methods can be modeled as state transitions • Test cases are sequences of method calls that traverse the state machine model

State machine model can be derived from specification (functional testing), code (structural testing), or both.

Testing with State Diagrams: • A statechart (called a “state diagram” in UML) may be produced as part of a specification or design - May also be implied by a set of message sequence charts (interaction diagrams), or other modeling formalisms. • Two options: 1, Convert (“flatten”) into standard finite-state machine, then derive test cases 2, Use state diagram model directly

Intraclass data flow testing

Exercise sequences of methods • From setting or modifying a field value • To using that field value

The intraclass control flow graph - control flow through sequences of method calls: • Control flow for each method • node for class • edges: from node class to the start nodes of the methods; from the end nodes of the methods to node class.

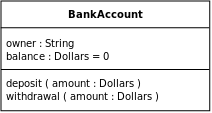

Interclass Testing

The first level of integration testing for object-oriented software - Focus on interactions between classes

Bottom-up integration according to “depends” relation - A depends on B - Build and test B, then A

Start from use/include hierarchy - Implementation-level parallel to logical “depends” relation

• Class A makes method calls on class B

• Class A objects include references to class B methods - but only if reference means “is part of”

In software engineering, a class diagram in the Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a type of static structure diagram that describes the structure of a system by showing the system’s classes, their attributes, operations (or methods), and the relationships among objects.

Dependency is a weaker form of bond that indicates that one class depends on another because it uses it at some point in time. One class depends on another if the independent class is a parameter variable or local variable of a method of the dependent class.

Interactions in Interclass Tests:

- Proceed bottom-up

- Consider all combinations of interactions

- example: a test case for class

Orderincludes a call to a method of classModel, and the called method calls a method of classSlot, exercise all possible relevant states of the different classes. - problem: combinatorial explosion of cases

- so select a subset of interactions:

- arbitrary or random selection

- plus all significant interaction scenarios that have been previously identified in design and analysis: sequence + collaboration diagrams

- example: a test case for class

Using Structural Information: • Start with functional testing: the specification (formal or informal) is the first source of information • Then add information from the code (structural testing)

Interclass structural testing

Working “bottom up” in dependence hierarchy • Dependence is not the same as class hierarchy; not always the same as call or inclusion relation. • May match bottom-up build order

Starting from leaf classes, then classes that use leaf classes,…

Summarize effect of each method: Changing or using object state, or both - Treating a whole object as a variable (not just primitive types)

Polymorphism and dynamic binding

One variable potentially bound to methods of different (sub-)classes.

The combinatorial approach: identify a set of combinations that cover all pairwise combinations of dynamic bindings.

Inheritance

When testing a subclass, We would like to re-test only what has not been thoroughly tested in the parent class. But we should test any method whose behavior may have changed.

Reusing Tests with the Testing History Approach:

- Track test suites and test executions

- determine which new tests are needed

- determine which old tests must be re-executed

- New and changed behavior …

- new methods must be tested

- redefined methods must be tested, but we can partially reuse test suites defined for the ancestor

- other inherited methods do not have to be retested

Abstract methods (and classes) - Design test cases when abstract method is introduced (even if it can t be executed yet)

Behavior changes • Should we consider a method “redefined” if another new or redefined method changes its behavior? • The standard “testing history” approach does not do this • It might be reasonable combination of data flow (structural) OO testing with the (functional) testing history approach

Testing exception handling

Exceptions create implicit control flows and may be handled by different handlers.

Impractical to treat exceptions like normal flow • too many flows: every array subscript reference, every memory, allocation, every cast, … • multiplied by matching them to every handler that could appear immediately above them on the call stack. • many actually impossible

So we separate testing exceptions, and ignore program error exceptions (test to prevent them, not to handle them)

What we do test: Each exception handler, and each explicit throw or re-throw of an exception.

Integration Testing

Unit (module) testing is a foundation, unit level has maximum controllability and visibility.

Integration testing may serve as a process check

• If module faults are revealed in integration testing, they signal inadequate unit testing

• If integration faults occur in interfaces between correctly implemented modules, the errors can be traced to module breakdown and interface specifications.

Integration test plan drives and is driven by the project “build plan”

Integration test plan drives and is driven by the project “build plan”

Structural orientation: Modules constructed, integrated and tested based on a hierarchical project structure - Top-down, Bottom-up, Sandwich, Backbone

Functional orientation: Modules integrated according to application characteristics or features - Threads, Critical module.

A “thread” is a portion of several modules that together provide a user-visible program feature.

Component-based software testing

Working Definition of Component • Reusable unit of deployment and composition • Characterized by an interface or contract • Often larger grain than objects or packages - A complete database system may be a component

Framework • Skeleton or micro-architecture of an application • May be packaged and reused as a component, with “挂钩 hooks” or “插槽 slots” in the interface contract

Design patterns • Logical design fragments • Frameworks often implement patterns, but patterns are not frameworks. Frameworks are concrete, patterns are abstract

Component-based system • A system composed primarily by assembling components, often “Commercial off-the-shelf” (COTS) components • Usually includes application-specific “glue code”

Component Interface Contracts • Application programming interface (API) is distinct from implementation • Interface includes everything that must be known to use the component: More than just method signatures, exceptions, etc; May include non-functional characteristics like performance, capacity, security; May include dependence on other components.

Testing a Component: Producer View • Thorough unit and subsystem testing • Thorough acceptance testing: Includes stress and capacity testing

Testing a Component: User View • Major question: Is the component suitable for this application? • Reducing risk: Trial integration early

System, Acceptance, and Regression Testing

System Testing

Characteristics: • Comprehensive (the whole system, the whole spec) • Based on specification of observable behavior: Verification against a requirements specification, not validation, and not opinions • Independent of design and implementation

Independence: Avoid repeating software design errors in system test design.

Maximizing independence: • Independent V&V: System (and acceptance) test performed by a different organization. • Independence without changing staff: Develop system test cases early

System tests are often used to measure progress. As project progresses, the system passes more and more system tests. Features exposed at top level as they are developed.

System testing is the only opportunity to verify Global Properties - Performance, latency, reliability, … Especially to find unanticipated effects, e.g., an unexpected performance bottleneck.

Context-Dependent Properties is beyond system-global: Some properties depend on the system context and use, Example: • Performance properties depend on environment and configuration • Privacy depends both on system and how it is used • Security depends on threat profiles

Stress Testing

When a property (e.g., performance or real-time response) is parameterized by use - requests per second, size of database,… Extensive stress testing is required - varying parameters within the envelope, near the bounds, and beyond.

Often requires extensive simulation of the execution environment, and requires more resources (human and machine) than typical test cases - Separate from regular feature tests, Run less often, with more manual control.

Capacity, Security, Performance, Compliance, Documentation Testing.

Acceptance testing

Estimating dependability, measuring quality, not searching for faults. Requires valid statistical samples from operational profile(model), and a clear, precise definition of what is being measured.

Quantitative dependability goals are statistical: • Reliability: Survival Probability - when function is critical during the mission time. • Availability: The fraction of time a system meets its specification - Good when continuous service is important but it can be delayed or denied • Failsafe: System fails to a known safe state • Dependability: Generalisation - System does the right thing at right time

Usability, Reliability, Availability/Reparability Testing

System Reliability

The reliability $R_F(t)$ of a system is the probability that no fault of the class $F$ occurs (i.e. system survives) during time $t \sim (t_{init}, t_{failure})$.

Failure Probability $Q_F(t) = 1 -R_F(t)$.

When the lifetime of a system is exponentially distributed, the reliability of the system is: $R(t) = e^{-\lambda t}$ where the parameter $\lambda$ is called the failure rate.

MTTF: Mean Time To (first) Failure, or Expected Life. $ MTTF = E(t_f) = \int_0^\infty R(t)dt = \frac{1}{\lambda}$

Serial System Reliability: Serially Connected Components. Assuming the failure rates of components are statistically independent, The overall system reliability:

$$R_{ser}(t) = \prod_{i=1}^n R_i(t) = e^{-t(\lambda_{ser})} = e^{-t(\sum_{i=1}^n \lambda_i)}$$$R_i(t) = e^{-\lambda_i t}$ is reliability of a single component $i$.

Parallel System Reliability: Parallel Connected Components.

$$R_{par}(t) = 1 - Q_{par}(t) = 1 - \prod_{i=1}^n Q_i(t) = 1 - \prod_{i=1}^n (1 - e^{-\lambda_i t}) = 1 - \prod_{i=1}^n (1 - R_i(t)) $$For example: · if one is to build a serial system with 100 components each of which had a reliability of 0.999, the overall system reliability would be $0.999^{100} = 0.905$. · Consider 4 identical modules are connected in parallel, System will operate correctly provided at least one module is operational. If the reliability of each module is 0.95, the overall system reliability is $1-(1-0.95)^4 = 0.99999375$.

Statistical testing is necessary for critical systems (safety critical, infrastructure, …), but difficult or impossible when operational profile is unavailable or just a guess, or when reliability requirement is very high.

Process-based Measures

Based on similarity with prior projects, less rigorous than statistical testing.

System testing process - Expected history of bugs found and resolved: • Alpha testing: Real users, controlled environment • Beta testing: Real users, real (uncontrolled) environment • May statistically sample users rather than uses • Expected history of bug reports

Regression Testing

Ideally, software should improve over time. But changes can both • Improve software, adding features and fixing bugs • Break software, introducing new bugs - regressions

Tests must be re-run after any changes.

Make use of different techniques for selecting a subset of all tests to reduce the time and cost for regression testing.

Regression Test Selection

From the entire test suite, only select subset of test cases whose execution is relevant to changes.

Code-based Regression Test Selection: Only execute test cases that execute changed or new code.

Control-flow and Data-flow Regression Test Selection: Re-run test cases only if they include changed elements – elements may be modified control flow nodes and edges, or definition-use (DU) pairs in data flow. To automate selection: • Tools record changed elements touched by each test case - stored in database of regression test cases • Tools note changes in program • Check test-case database for overlap

Specification-based Regression Test Selection: • Specification-based prioritization: Execute all test cases, but start with those that related to changed and added features.

Test Set Minimization

Identify test cases that are redundant and remove them from the test suite to reduce its size. • Maximize coverage with minimum number of test cases. • Stop after a pre-defined number of iterations • Obtain an approximate solution by using a greedy heuristic

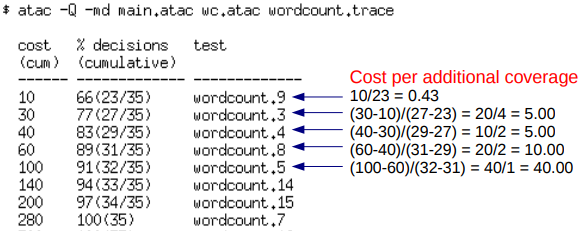

Test Set Prioritisation

• Sort test cases in order of increasing cost per additional coverage

• Select the first test case

• Repeat the above two steps until k test cases are selected or max cost is reached (whichever is first).

Prioritized Rotating Selection: Execute some sooner than others, eventually execute all test cases. Possible priority schemes: • Round robin: Priority to least-recently-run test cases • Track record: Priority to test cases that have detected faults before - They probably execute code with a high fault density • Structural: Priority for executing elements that have not been recently executed - Can be coarse-grained: Features, methods, files.

Test-Driven Development (TDD)

Test-Driven Development (or test driven design) is a methodology.

• Short development iterations. • Based on requirement and pre-written test cases. • Produces code necessary to pass that iteration’s test. • Refactor both code and tests. • The goal is to produce working clean code that fulfills requirements.

Principle of TDD - Kent Beck defines: • Never write a single line of code unless you have a failing automated test. • Eliminate duplication

TDD uses Black-box Unit test: 1, 明确功能需求。 2, 为功能需求编写 test。 3, 运行测试,按理应该无法通过测试(因为还没写功能程序)。 4, 编写实现该功能的代码,通过测试。 5, 可选:重构代码(和 test cases),使其更快,更整洁等等。 6, 可选:循环此步骤

Automating Test Execution

Designing test cases and test suites is creative, but executing test cases should be automatic.

Example Tool Chain for Test Case Generation & Execution: Combine … • A combinatorial test case generation (genpairs.py) to create test data • DDSteps to convert from spreadsheet data to JUnit test cases • JUnit to execute concrete test cases

Scaffolding

Code to support development and testing. • Test driver: A “main” program for running a test • Test stubs: Substitute for called functions/methods/objects.

Stub is an object that holds predefined data and uses it to answer calls during tests. It is used when we cannot or don’t want to involve objects that would answer with real data or have undesirable side effects. 代指那些包含了预定义好的数据并且在测试时返回给调用者的对象。Stub 常被用于我们不希望返回真实数据或者造成其他副作用的场景。

• Test harness: Substitutes for other parts of the deployed environment

• Comparison-based oracle: need predicted output for each input. Fine for a small number of hand-generated test cases, e.g. hand-written JUnit test cases.

• Self-Checking Code as Oracle: oracle written as self-checks, possible to judge correctness without predicting results. Advantages and limits: Usable with large, automatically generated test suites, but often only a partial check.

• Capture and Replay: If human interaction is required, capture the manually run test case, replay it automatically. With a comparison-based test oracle, behavior same as previously accepted behavior.

Security Testing

“Regular” testing aims to ensure that the program meets customer requirements in terms of features and functionality. Tests “normal” use cases - Test with regards to common expected usage patterns.

Security testing aims to ensure that program fulfills security requirements. Often non-functional. More interested in misuse cases.

Two common approaches: • Test for known vulnerability types • Attempt directed or random search of program state space to uncover the “weird corner cases”

Penetration testing

• Manually try to “break” software • Typically involves looking for known common problems.

Fuzz testing

Send semi-valid input to a program and observe its behavior. • Black-box testing - System Under Test (SUT) treated as a “black-box” • The only feedback is the output and/or externally observable behavior of SUT.

Input generation • Mutation based fuzzing: Start with a valid seed input, and “mutate” it. Can typically only find the “low-hanging fruit” - shallow bugs that are easy to find. • Generation based fuzzing: Use a specification of the input format (e.g. a grammar) to automatically generate semi-valid inputs - Very long strings, empty strings, Strings with format specifiers, “extreme” format strings, Very large or small values, values close to max or min for data type, Negative values. Almost invariably gives better coverage, but requires much more manual effort.

The Dispatcher: running the SUT on each input generated by fuzzer module.

The Assessor: automatically assess observed SUT behavior to determine if a fault was triggered.

Concolic testing

Concolic execution workflow: 1, Execute the program for real on some input, and record path taken. 2, Encode path as query to SMT solver and negate one branch condition 3, Ask the solver to find new satisfying input that will give a different path.

White-box testing method. • Input generated from control-structure of code to systematically explore different paths of the program. • Generational search (“whitebox fuzzing”): Performs concolic testing, but prioritizes paths based on how much they improve coverage.

Greybox fuzzing ▪ Coverage-guided semi-random input generation. ▪ High speed sometimes beats e.g. concolic testing, but shares some limitations with mutation-based fuzzing (e.g. magic constants, checksums).

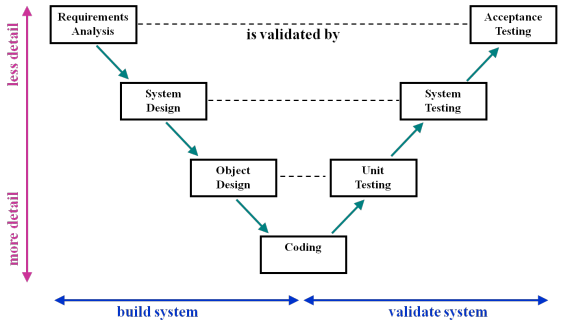

Software Process Models - Software Development

Waterfall model: Sequential, no feedback 1, Requirements 2, Design 3, Implementation 4, Testing 5, Release and maintenance

V-model: modified version of the waterfall model

• Tests are created at the point the activity they validate is being carried out. So, for example, the acceptance test is created when the systems analysis is carried out.

• Failure to meet the test requires a further iteration beginning with the activity that has failed the validation

• Tests are created at the point the activity they validate is being carried out. So, for example, the acceptance test is created when the systems analysis is carried out.

• Failure to meet the test requires a further iteration beginning with the activity that has failed the validation

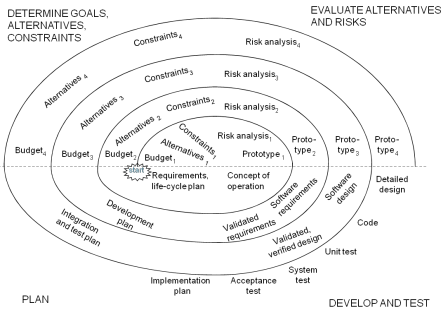

Boehm’s Spiral Model: focuse on controlling project risk and attempting formally to address project risk throughout the lifecycle.

• V&V activity is spread through the lifecycle with more explicit validation of the preliminary specification and the early stages of design. The goal here is to subject the early stages of design to V&V activity.

• At the early stages there may be no code available so we are working with models of the system and environment and verifying that the model exhibits the required behaviours.

• V&V activity is spread through the lifecycle with more explicit validation of the preliminary specification and the early stages of design. The goal here is to subject the early stages of design to V&V activity.

• At the early stages there may be no code available so we are working with models of the system and environment and verifying that the model exhibits the required behaviours.

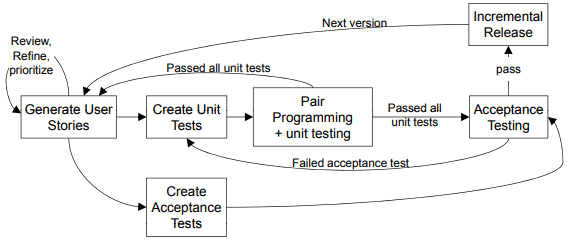

Extreme Programming (XP): one of [Agile Processes]

• Advocates working directly with code almost all the time.

• The 12 principles of XP summarise the approach.

• Advocates working directly with code almost all the time.

• The 12 principles of XP summarise the approach.

1, Test-driven development; 2, The planning game; 3, On-site customer; 4, Pair programming; 5, Continuous integration; 6, Refactoring; 7, Small releases; 8, Simple design; 9, System metaphor; 10, Collective code ownership; 11, Coding standards; 12, 40-hour work week;

• Development is test-driven. • Tests play a central role in refactoring activity. • “Agile” development mantra: Embrace Change.

Facebook’s Process Model

Perpetual development - a continuous development model. In this model, software will never be considered a finished product. Instead features are continuously added and adapted and shipped to users. Fast iteration is considered to support rapid innovation.

Planning and Monitoring the Process

Monitoring: Judging progress against the plan.

Quality process: Set of activities and responsibilities. Follows the overall software process in which it is embedded. • Example: waterfall software process ––> “V model”: unit testing starts with implementation and finishes before integration • Example: XP and agile methods ––> emphasis on unit testing and rapid iteration for acceptance testing by customers.

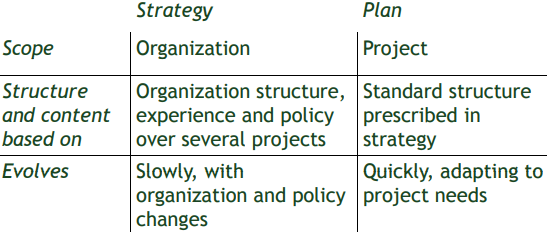

Strategies vs. Plans

Test and Analysis Strategy:

• Lessons of past experience: an organizational asset built and refined over time

• Body of explicit knowledge: amenable to improvement, reduces vulnerability to organizational change (e.g., loss of key individuals)

Test and Analysis Strategy:

• Lessons of past experience: an organizational asset built and refined over time

• Body of explicit knowledge: amenable to improvement, reduces vulnerability to organizational change (e.g., loss of key individuals)

Elements of a Strategy: • Common quality requirements that apply to all or most products - unambiguous definition and measures • Set of documents normally produced during the quality process - contents and relationships • Activities prescribed by the overall process - standard tools and practices • Guidelines for project staffing and assignment of roles and responsibilities

Main Elements of a Plan: • Items and features to be verified - Scope and target of the plan • Activities and resources - Constraints imposed by resources on activities • Approaches to be followed - Methods and tools • Criteria for evaluating results

Schedule Risk

• Critical path = chain of activities that must be completed in sequence and that have maximum overall duration • Critical dependence = task on a critical path scheduled immediately after some other task on the critical path

Risk Planning

• Generic management risk: personnel, technology, schedule • Quality risk: development, execution, requirements

Contingency Plan

• Derives from risk analysis • Defines actions in response to bad news - Plan B at the ready

Process Monitoring

• Identify deviations from the quality plan as early as possible and take corrective action

Process Improvement

Orthogonal Defect Classification (ODC) • Accurate classification schema: for very large projects, to distill an unmanageable amount of detailed information • Two main steps 1, Fault classification: when faults are detected, when faults are fixed. 2, Fault analysis

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) • Technique for identifying and eliminating process faults • Four main steps 1, What are the faults? 2, When did faults occur? When, and when were they found? 3, Why did faults occur? 4, How could faults be prevented?