TLDR

In order to train more dependable models, there are two known options: outcome supervision, which gives feedback on the final result, and process supervision, which provides feedback on each intermediate reasoning step.

This papers provides two finding:

- The use of process supervision yields significantly better results than outcome supervision when training models to solve problems from the challenging MATH dataset.

- The efficacy of process supervision is significantly improved by active learning.

The exclusive focus of this paper is to provide insights on training the most reliable reward model.

Papers: Lightman, Hunter, et al. Let’s Verify Step by Step. arXiv:2305.20050, arXiv, 31 May 2023. arXiv.org, http://arxiv.org/abs/2305.20050.

Why

Even the most advanced models are susceptible to generating false information, as they tend to create facts when they are uncertain (Bubeck et al., 2023). These hallucinations (Maynez et al., 2020) can be especially problematic in areas that involve multi-step reasoning, as a single logical mistake can disrupt a much larger solution.

Methods

To deal with hallucinations, one effective approach is to train reward models to differentiate between desirable and undesirable outputs. These reward models can then be utilized in a reinforcement learning pipeline or to conduct search via rejection sampling.

Outcome-supervised reward models (ORMs) are trained solely on the final result of the model’s chain-of-thought. On the other hand, process-supervised reward models (PRMs) receive feedback for each step in the chain-of-thought.

This paper prefer PRMs for several reasons:

- Process supervision provides more accurate feedback as it identifies the exact location of any errors that may occur.

- It is easier for humans to interpret.

- It directly incentivizes models to follow a human-endorsed chain-of-thought.

- In the field of logical reasoning, models trained with outcome supervision often use incorrect reasoning to arrive at the correct final answer (Zelikman et al., 2022; Creswell et al., 2022). Process supervision has been demonstrated to alleviate this misaligned behavior (Uesato et al., 2022).

How to do PRMs

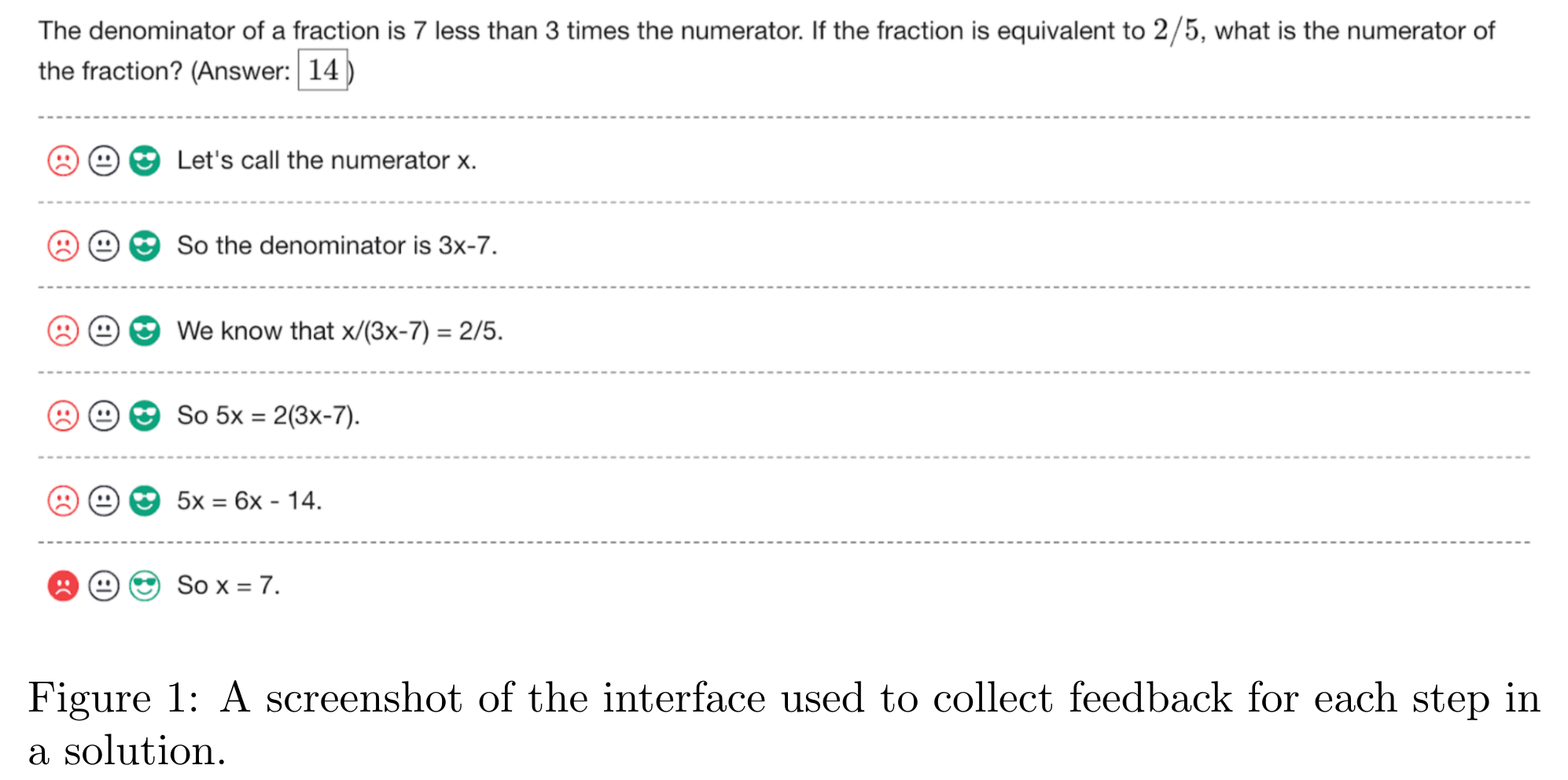

The process supervision approach relies on human data-labelers to provide supervision by labeling the correctness of each step in the model-generated solutions.

- To collect the process supervision data, present step-by-step solutions to MATH problems sampled by the large-scale generator to human data-labelers. Their task is to assign each step in the solution a label of positive, negative, or neutral. A positive label indicates that the step is correct and reasonable, while a negative label indicates that the step is either incorrect or unreasonable. A neutral label indicates ambiguity.

- They aim to surface solutions that are more likely to deceive their best reward model. To achieve this, they strategically select which solutions to show data-labelers. Specifically, they choose to surface convincing wrong-answer solutions. They use the term convincing to refer to solutions that are rated highly by current best PRM, and they use wrong-answer to refer to solutions that reach an incorrect final answer.

- The PRMs are trained to predict the correctness of each step after the last token in each step. This prediction takes the form of a single token, and maximize the log-likelihood of these target tokens during training.

- Define the PRM score for a solution as the probability that every step is correct under the PRM. This can be implemented as the product of the correctness probabilities for each step.

- When providing process supervision, they deliberately choose to supervise only up to the first incorrect step. This simplifies the comparison between outcome and process supervision.

To reduce the reliance on expensive human feedback, they employ a large-scale model to oversee the training of smaller-scale models.

Active Learning

Generally, the active learning method’s performance is not stable or predictable. However, it is still worth taking a closer look. They first train a small-scale reward model, PRMselector, using a single sample from each problem, and then use this model to evaluate 1000 samples per problem. For training larger reward models, they select N samples per problem, with 80% being the most convincing wrong-answer samples (according to PRMselector), and 20% being the most convincing samples that remain (right or wrong-answer). They score the selected samples using PRMlarge and use those scores for training. This process ensures that all samples are relatively convincing under PRMselector, that a large fraction are known to contain at least one mistake, and that the dataset is not heavily biased towards wrong-answer solutions.

Models

- All the large-scale models are fine-tuned from the base GPT-4 model (OpenAI, 2023), which was pre-trained solely to predict the next token and not with any Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) (Christiano et al., 2017).

- The small-scale base models are designed similarly to GPT-4, but they were pre-trained with approximately 200 times less compute.

- Additionally, they fine-tune all models on a dataset of around 1.5 billion math-relevant tokens, which they refer to as MathMix. Yet this dataset are not open-sourced.

- To simplify parsing individual steps, they train the generator to produce solutions in a step-by-step format separated by newlines. Specifically, they few-shot generate solutions to MATH training problems, filter to those that reach the correct final answer, and fine-tune the base model on this dataset for a single epoch. This step is not intended to teach the generator new skills, but rather to train it to produce solutions in the desired format.

Results/Analysis/Findings

Task/Dataset: The process supervision dataset, PRM800K, which includes 800K step-level labels across 75K solutions to 12K problems.

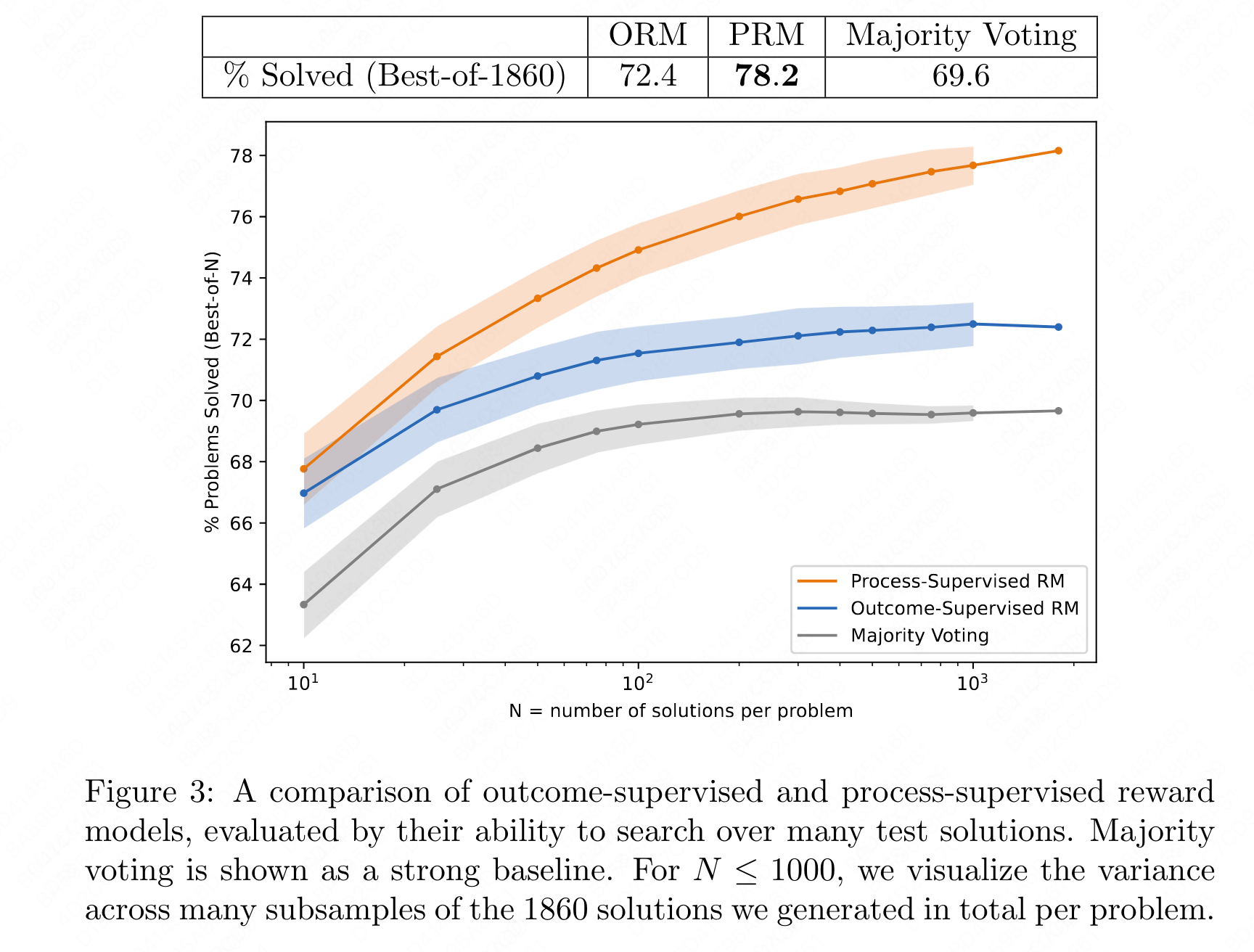

Evaluation: To evaluate the effectiveness of a reward model, they test its ability to perform a best-of-N search over uniformly sampled solutions from the generator. For each test problem, they select the solution with the highest rank determined by the reward model, automatically grade it based on its final answer, and report the fraction of correct solutions. A more reliable reward model will select the correct solution more frequently.

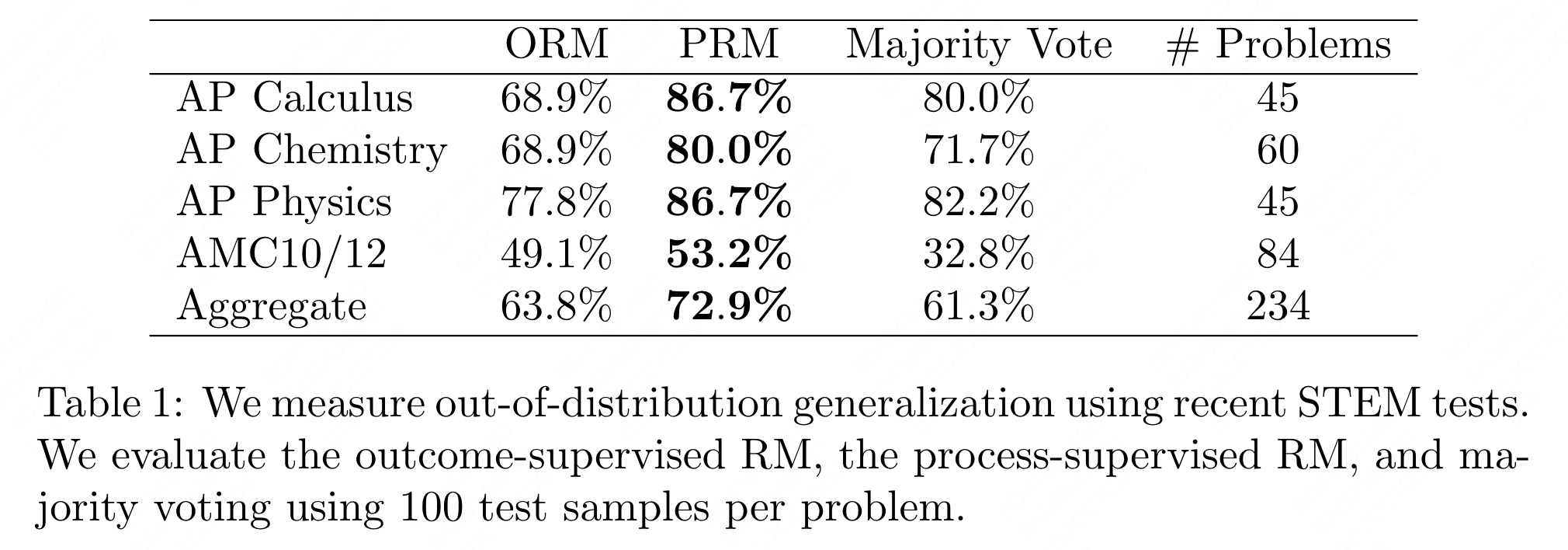

Out-of-distribution generalization (OOD): the PRM model can tolerate a moderate amount of distribution shift, and its strong performance remains consistent even when tested on new and unfamiliar questions.

Alignment Impact: Process supervision is more likely to generate interpretable reasoning since it encourages models to follow a process that is endorsed by humans. Process supervision is also inherently safer as it directly rewards an aligned chain of thought, rather than relying on outcomes as a proxy for aligned behavior.

In conclusion:

- process supervision can train reward models that are much more reliable than those trained with outcome supervision. Their state-of-the-art PRM model can solve 78.2% of problems from a representative subset of the MATH test set.

- A large reward model can accurately approximate human supervision for smaller reward models, and it can be used to efficiently conduct large-scale data collection ablations.

Reference

- S. Bubeck, V. Chandrasekaran, R. Eldan, J. Gehrke, E. Horvitz, E. Kamar, P. Lee, Y. T. Lee, Y. Li, S. Lundberg, et al.

- A. Askell, Y. Bai, A. Chen, D. Drain, D. Ganguli, T. Henighan, A. Jones, N. Joseph, B. Mann, N. DasSarma, et al. A general language assistant as a laboratory for alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.00861, 2021.

- P. F. Christiano, J. Leike, T. Brown, M. Martic, S. Legg, and D. Amodei. Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017.

- K. Cobbe, V. Kosaraju, M. Bavarian, M. Chen, H. Jun, L. Kaiser, M. Plappert, J. Tworek, J. Hilton, R. Nakano, et al. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168, 2021.

- A. Cotra. Without specific countermeasures, the easiest path to transformative AI likely leads to AI takeover. https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/pRkFkzwKZ2zfa3R6H/ without-specific-countermeasures-the-easiest-path-to, 2022.

- A. Creswell, M. Shanahan, and I. Higgins. Selection-inference: Exploiting large language models for interpretable logical reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.09712, 2022.

- T. Everitt, V. Krakovna, L. Orseau, M. Hutter, and S. Legg. Reinforcement learning with a corrupted reward channel. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.08417, 2017.

- L. Gao, J. Schulman, and J. Hilton. Scaling laws for reward model overoptimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.10760, 2022.

- D. Hendrycks, C. Burns, S. Kadavath, A. Arora, S. Basart, E. Tang, D. Song, and J. Steinhardt. Measuring mathematical problem solving with the math dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.03874, 2021.

- T. Kojima, S. S. Gu, M. Reid, Y. Matsuo, and Y. Iwasawa. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.11916, 2022.

- A. Lewkowycz, A. Andreassen, D. Dohan, E. Dyer, H. Michalewski, V. Ramasesh, A. Slone, C. Anil, I. Schlag, T. Gutman-Solo, et al. Solving quantitative reasoning problems with language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.14858, 2022.

- Y. Li, Z. Lin, S. Zhang, Q. Fu, B. Chen, J.-G. Lou, and W. Chen. On the advance of making language models better reasoners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.02336, 2022.

- J. Maynez, S. Narayan, B. Bohnet, and R. McDonald. On faithfulness and factuality in abstractive summarization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.00661, 2020.

- R. Nakano, J. Hilton, S. Balaji, J. Wu, L. Ouyang, C. Kim, C. Hesse, S. Jain, V. Kosaraju, W. Saunders, et al. Webgpt: Browser-assisted questionanswering with human feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.09332, 2021.

- E. Nichols, L. Gao, and R. Gomez. Collaborative storytelling with large-scale neural language models. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM SIGGRAPH Conference on Motion, Interaction and Games, pages 1–10, 2020.

- M. Nye, A. J. Andreassen, G. Gur-Ari, H. Michalewski, J. Austin, D. Bieber, D. Dohan, A. Lewkowycz, M. Bosma, D. Luan, et al. Show your work: Scratchpads for intermediate computation with language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.00114, 2021.

- OpenAI. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

- L. Ouyang, J. Wu, X. Jiang, D. Almeida, C. L. Wainwright, P. Mishkin, C. Zhang, S. Agarwal, K. Slama, A. Ray, et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.02155, 2022.

- J. Shen, Y. Yin, L. Li, L. Shang, X. Jiang, M. Zhang, and Q. Liu. Generate & rank: A multi-task framework for math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.03034, 2021.

- N. Stiennon, L. Ouyang, J. Wu, D. Ziegler, R. Lowe, C. Voss, A. Radford, D. Amodei, and P. F. Christiano. Learning to summarize with human feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33:3008–3021, 2020.

- A. Stuhlm ̈ uller and J. Byun. Supervise process, not outcomes. https://ought. org/updates/2022-04-06-process, 2022.

- J. Uesato, N. Kushman, R. Kumar, F. Song, N. Siegel, L. Wang, A. Creswell, G. Irving, and I. Higgins. Solving math word problems with process-and outcome-based feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.14275, 2022.

- X. Wang, J. Wei, D. Schuurmans, Q. Le, E. Chi, and D. Zhou. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.11171, 2022.

- J. Wei, X. Wang, D. Schuurmans, M. Bosma, E. Chi, Q. Le, and D. Zhou. Chain of thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.11903, 2022.

- E. Zelikman, Y. Wu, J. Mu, and N. Goodman. Star: Bootstrapping reasoning with reasoning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35: 15476–15488, 2022.

- D. M. Ziegler, N. Stiennon, J. Wu, T. B. Brown, A. Radford, D. Amodei, P. Christiano, and G. Irving. Fine-tuning language models from human preferences. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.08593, 2019.