Stanford CS106B Programming Abstractions 和 CS106A 的学习笔记. 课程作业(cs106b spring 2017)实现代码见 https://github.com/ShootingSpace/cs106b-programming-abstraction

Topics:

A: Intro (by Java) B: Recursion, algorithms analysis (sort/search/hash), dynamic data structures (lists, trees, heaps), data abstraction (stacks, queues, maps), implementation strategies/tradeoffs

Purposes

- become acquainted with the C++ programming language

- learn more advanced programming techniques

- explore classic data structures and algorithms

- and apply these tools to solving complex problems

Reference

- Text Book: Data Structures & Algorithm Analysis in C++, 4th ed, by Mark A. Weiss

- Text Book: Programming Abstractions in C++ 1st Edition by Eric Roberts

- Text Book: Algorithms, 4th Edition

- Blog: Red Blob Games, Amit’s A* Pages

Coding style

Why writing clean, well-structured code

- The messy code trap

- harder to build and debug

- harder to clean up

- Decomposition

- Decompose the problem, not the programs, program is written from the already decomposed framework.

- Logical and readable

- Methods should be short and to the point,

- Strive to design methods that are general enough for a variety of situations and achieve specifics trough use of parameters.

- Avoid redundants methods.

- Avoid repeated lines or methods.

- Readable code:

- Writing readable code not only help future readers but also help avoid your own bugs: Because bugs are codes that fail to expresses idea in mind.

- Reader can see the algorithmic idea when sweeping the code.

Works correctly in all situations: Using a listing of specific test cases to exercise the program on.

The overall approach is straight-forward, data structure is cleanly organized, tasks are nicely decomposed, algorithms are clear and easy to follow, comments are helpful, layout is consistent.

How to write clean, well-structured code?

- Choosing good names for variables

- Name reflect what it stores, normally nouns;

- In Java, conventionly, begin variables with the first word lowercase, and upper case later words

bestScore - Widely used idiomatic one-letter names:

i, j, kfor int loop counters;x, y, zfor coordinates.

- Choosing good names for methods

- Name reflect the action they perform, verbs normally;

- The prefixes

getandsethave a typical role: A get method gets a piece of information from an object; set methods are used to pass a value in to an object - Returning a boolean are ofter named starting with

isorhas.

- Using whitespace to separate logical parts: Put in blank lines to separate the code into its natural sub sections that accomplis logical sub-parts of the whole algoriithm. Each little section might have a comment to describe what it accomplishes.

- Use Indentation to show hierarchy structure

- Comments

- Attributions: consider as an important tennet of academic integrity.

Comments

Examples of information you might include in comments:

- General overview. What are the goals and requirements of this program? this function? The overview comment should also contain author and version information: who worked on this file and when.

- Data structures. How is the data stored? How is it ordered, searched, accessed?

- Design decisions. Why was a particular data structure or algorithm chosen? What other strategies were tried and rejected?

- Error handling. How are error conditions handled? What assumptions are made? What happens if those assumptions are violated?

- Nitty-gritty code details. Comments are invaluable for explaining the inner workings of particularly complicated (often labeled “clever”) paths of the code.

- Planning for the future. How might one make modifications or extensions later?

- And more… (This list is by no means exhaustive)

ADT

An abstract data type is a set of objects together with a set of operations. Abstract data types are mathematical abstractions; nowhere in an ADT’s definition is there any mention of how the set of operations is implemented. Objects such as lists, sets, and graphs, along with their operations, can be viewed as ADTs. Also there are search tree, set, hash table, priority queue.

- Client uses class as abstraction

- Invokes public operations only

- Internal implementation not relevant!

- Client can’t and shouldn’t muck with internals: Class data should private

- Imagine a “wall” between client and implementor

- Wall prevents either from getting involved in other’s business

- Interface is the “chink” in the wall

- Conduit allows controlled access between the two

- Consider Lexicon

- Abstraction is a word list, operations to verify word/prefix

- How does it store list? using array? vector? set? does it matter to client?

Why ADTs?

- Abstraction: Client insulated from details, works at higher-level

- Encapsulation: Internals private to ADT, not accessible by client

- Independence: Separate tasks for each side (once agreed on interface)

- Flexibility: ADT implementation can be changed without affecting client

The C++ language includes, in its library, an implementation of common data structures. This part of the language is popularly known as the Standard Template Library (STL). In general, these data structures are called collections or containers.

Iterators

In the STL, a position is represented by a nested type, iterator.

Getting an Iterator

iterator begin( )returns an appropriate iterator representing the first item in the container.iterator end( )returns an appropriate iterator representing the endmarker in the container (i.e., the position after the last item in the container).

Iterator Methods

* itr++ and ++itr advances the iterator itr to the next location. Both the prefix and postfix forms are allowable.

* itr returns a reference to the object stored at iterator itr’s location. The reference returned may or may not be modifiable (we discuss these details shortly).

* itr1==itr2 / itr1!=itr2, returns true if iterators itr1 and itr2 refer to the same / different location and false otherwise.

Container Operations that require Iterators. The three most popular methods that require iterators are those that add or remove from the list (either a vector or list) at a specified position:

iterator insert( iterator pos, const Object & x ): addsxinto the list, prior to the position given by theiterator pos. This is a constant-time operation for list, but not for vector. The return value is an iterator representing the position of the inserted item.iterator erase( iterator pos ): removes the object at the position given by the iterator. This is a constant-time operation for list, but not for vector. The return value is the position of the element that followed pos prior to the call. This operation invalidates pos, which is now stale, since the container item it was viewing has been removed.- iterator erase( iterator start, iterator end ): removes all items beginning at position start, up to, but not including end. Observe that the entire list can be erased by the call c.erase( c.begin( ), c.end( ) )

- Range for loop: C++11 also allows the use of the reserved word auto to signify that the compiler will automatically infer the appropriate type,

- for simple data type:

for( auto x : squares ) cout<< x;- for complicate data type like map: Each element of the container is a

map<K, V>::value_type, which is a typedef forstd::pair<const K, V>. Consequently, you’d write this as

for (auto& kv : myMap) { std::cout << kv.first << " has value " << kv.second << std::endl; }

Recursion

Helper Function

- No clear definition of helper function

- How to utilize helper function to help constructing recursion algarithm: construct a same-name recursive function with extra parameters to pass in.

- In some other cases, decomposition with several step into a function is itself a helper function, which help to make the main function simple and clean.

Exhaustive recursion

Permutations/subsets are about choice

- Both have deep/wide tree of recursive calls

- Depth represents total number of decisions made

- Width of branching represents number of available options per decision

- Explores every possible option at every decision point, typically very expensive, N! permutations, 2N subsets

Recursive Backtracking

Partial exploration of exhaustive space. In the case that if we are interested in finding any solution, whichever one that works out first is fine. If we eventually reach our goal from here, we have no need to consider the paths not taken. However, if this choice didn’t work out and eventually leads to nothing but dead ends; when we backtrack to this decision point, we try one of the other alternatives.

- The back track based on the stacks of recursion, if a stack return false (or fail result), we back to previous stack and try another way(un-making choice).

- Need something return(normally bool) to step out of the entire recursion once any one solution found.

- One great tip for writing a backtracking function is to abstract away the details of managing the configuration (what choices are available, making a choice, checking for success, etc.) into other helper functions so that the body of the recursion itself is as clean as can be. This helps to make sure you have the heart of the algorithm correct and allows the other pieces to be developed, test, and debugged independently.

Pointer

lvalue: In C++, any expression that refers to an internal memory location capable of storing data is called an lvalue (pronounced “ell-value”). x = 1.0;

Declaring pointer variables

int main() {

--------------------------------------------------

// Declaration, in the stack

// Not yet initialized!

int num;

int *p, *q;

// If cout << num << p << q << endl;

// There will be junk number, junk address.

// If now *p=10, it may blow up, because what *p point to is an address points to somewhere around that could be invalid.

---------------------------------------------------

// new operator allocate memory from the heap, returns address

p = new int; // P -----> [ int ] (heep 1000)

*p = 10; // P -----> [ 10 ] (heep 1000)

q = new int; // P -----> [ int ] (heep 1004)

*q = *p; // q -----> [ 10 ] (heep 1004)

q = p; // q -----> [ 10 ] (heep 1000)

// [ 10 ] (heep 1004) became orphan, and could not be reclaim back

---------------------------------------------------

delete p; // [ 10 ] (heep 1000)memory was reclaimed and free,

// and available for others as [ ](heep 1000),

// but p still hold the address

delete q; // bad idea, [ 10 ](heep 1000) already been reclaimed!

q = NULL; // NULL is zero pointer, means the pointer does not hold any address,

// used as sentinel value, sometimes better than delete.

// Accessing "deleted" memory has unpredictable consequences

---------------------------------------------------

// int *p declaration reserves only a single word, which is large enough to hold a machine address.

// ≠

// int *p = NULL declare pointer p as nullptr

---------------------------------------------------

(*newOne).name = name // "." > "*"

newOne->name = name

Use of pointer

Big program that contains a certain amout of classes and objects that are share some relationship. Instead of copying data from each other, using pointer to point to specific data is better:

- Saves space by not repeating the same information.

- If some objects gets new information to update, change in one place only!

Dynamic allocation

Request memory: To acquire new memory when you need it and to free it explicitly when it is no longer needed. Acquiring new storage when the program is running. While the program is running, you can reserve part of the unallocated memory, leaving the rest for subsequent allocations.

The pool of unallocated memory available to a program is called the heap.

int *p = new int; //new operator to allocate memory from the heap

In its simplest form, the new operator takes a type and allocates space for a variable of that type located in the heap.

The call to new operator will return the address of a storage location in the heap that has been set aside to hold an integer.

Free occupied memory: Delete which takes a pointer previously allocated by new and returns the memory associated with that pointer to the heap.

Tree

- Node, tree, subtree, parent, child, root, edge, leaf

- For any node ni, the depth of ni is the length of the unique path from the root to ni. The height of ni is the length of the longest path from ni to a leaf

- Rules for all trees

- Recursive branching structure

- Single root node

- Every node reachable from root by unique path

Binary tree

Each node has at most 2 children.

Binary search tree

- All nodes in left subtree are less than root, all nodes in right subtree are greater.

- Arranged for efficient search/insert.

- It is the basis for the implementation of two library collections classes, set and map.

- Most operations’ average running time is O(log N).

Operating on trees

Many tree algorithms are recursive

- Handle current node, recur on subtrees

- Base case is empty tree (NULL)

Tree traversals to visit all nodes, order of traversal:

- Pre: cur, left, right

- In: left, cur, right

- Post: left, right, cur

- Others: level-by-level, reverse orders, etc

Balanced Search Trees

Binary search tree have poor worst-case performance.

To make costs are guaranteed to be logarithmic, no matter what sequence of keys is used to construct them, the ideal is to keep binary search trees perfectly balanced. Unfortunately, maintaining perfect balance for dynamic insertions is too expensive. So consider data structure that slightly relaxes the perfect balance requirement to provide guaranteed logarithmic performance not just for the insert and search operations, but also for all of the ordered operations (except range search).

AVL tree

Adelson-Velskii and Landis tree is a binary search tree with a balance condition.

- Track balance factor for each node: Height of right subtree - height of left subtree information is kept for each node (in the node structure)

- For every node in the tree, the height of the left and right subtrees can differ by at most 1 (Balance factor = 0 or 1).

- When balance factor hits 2, restructure

- Rotation moves nodes from heavy to light side

- Local rearrangement around specific node

- When finished, node has 0 balance factor

- Single rotation: one time rotation between new insert node and its parent node

- Double rotation: two single rotation of the new insert node

2-3 trees

Allow the nodes in the tree to hold more than one key: 3-nodes, which hold three links and two keys.

A 2-3 search tree is a tree that is either empty or

- A 2-node, with one key (and associated value) and two links, a left link to a 2-3 search tree with smaller keys, and a right link to a 2-3 search tree with larger keys

- A 3-node, with two keys (and associated values) and three links, a left link to a 2-3 search tree with smaller keys, a middle link to a 2-3 search tree with keys between the node’s keys, and a right link to a 2-3 search tree with larger keys

- A perfectly balanced 2-3 search tree is one whose null links are all the same distance from the root.

The concept guarantee that search and insert operations in a 2-3 tree with N keys are to visit at most lg N nodes.

- But its dicrect implementation is inconvenient: Not only is there a substantial amount of code involved, but the overhead incurred could make the algorithms slower than standard BST search and insert.

- Consider a simple representation known as a red-black BST that leads to a natural implementation.

Binary Heap

A heap is a binary tree that is completely filled, with the possible exception of the bottom level, which is filled from left to right. Such a tree is known as a complete binary tree.

- A heap data structure consist of an array (of Comparable objects) and an integer representing the current heap size.

- For any element in array position i, the left child is in position 2i, the right child is in the cell after the left child [2i + 1], and the parent is in position [i/2].

- Heap-Order Property: For every node X, the key in the parent of X is smaller than (or equal to) the key in X. So to make find minimum operation quick.

Basic Heap Operation

insert: To insert an element X into the heap, create a hole in the next available location. Then Percolate up - swap X with its parent index (i/2) so long as X has a higher priority than its parent. Continue this process until X has no more lower priority parent.

//Percolate up

int hole = ++size;

binaryQueue[0]=std::move(*newOne);

for ( ; (priority < binaryQueue[hole/2].priority || (priority == binaryQueue[hole/2].priority && name < binaryQueue[hole/2].name) ); hole/=2) {

binaryQueue[hole] = std::move(binaryQueue[hole/2]);

}

binaryQueue[hole] = std::move(binaryQueue[0]);

deleteMin: When the minimum is removed, a hole is created at the root. Move the last element X in the heap to place in the root hole. Then Percolate down - swapp X with its more urgent-priority child [index (i2 or i2+1)] so long as it has a lower priority than its child. Repeat this step until X has no more higher priority child.

//Percolate down

int child;

for (; hole*2<=size;hole=child) {

child = hole*2;

if ( child!=size && (binaryQueue[child+1].priority<binaryQueue[child].priority || (binaryQueue[child+1].priority==binaryQueue[child].priority && binaryQueue[child+1].name<binaryQueue[child].name)) )

++child;

if ( binaryQueue[child].priority<priority_tobePerD || (binaryQueue[child].priority==priority_tobePerD && binaryQueue[child].name<name_tobePerD) ) {

binaryQueue[hole] = std::move(binaryQueue[child]);

} else break;

}

- Use integer division to avoid even odd index.

Priority Queues

A priority queue is a data structure that allows at least the following two operations: insert, and deleteMin, which finds, returns, and removes the minimum element in the priority queue.

Algorithm Analysis

Space/time, big-O, scalability

Big-O

- Computational complexity: The relationship between N and the performance of an algorithm as N becomes large

- Big-O notation: to denote the computational complexity of algorithms.

- Standard simplifications of big-O

- Eliminate any term whose contribution to the total ceases to be significant as N becomes large.

- Eliminate any constant factors.

- Worst-case versus average-case complexity Average-case performance often reflects typical behavior, while worst-case performance represents a guarantee for performance on any possible input.

- Predicting computational complexity from code structure

- Constant time: Code whose execution time does not depend on the problem size is said to run in constant time, which is expressed in big-O notation as O(1).

- Linear time: function that are executed exactly n times, once for each cycle of the for loop, O(N)

- Quadratic time: Algorithms like selection sort that exhibit O(N2) performance are said to run in quadratic tim

- For many programs, you can determine the computational complexity simply by finding the piece of the code that is executed most often and determining how many times it runs as a function of N

Space/time

- In general, the most important measure of performance is execution time.

- It also possible to apply complexity analysis to the amount of memory space required. Nowadays the memory is cheap, but it still matters when designing extreamly big programs, or APPs on small memory device, such as phones and wearable devices.

Sorting

There are lots of different sorting algoritms, from the simple to very complex. Some optimized for certain situations (lots of duplicates, almost sorted, etc.). So why do we need multiple algorithms?

Selection sort

Select smallest and swap to front/backend

void SelectionSort(Vector<int> &arr)

{

for (int i = 0; i < arr.size()-1; i++) {

int minIndex = i;

for (int j = i+1; j < arr.size(); j++) {

if (arr[j] < arr[minIndex])

minIndex = j;

}

Swap(arr[i], arr[minIndex]);

}

}

Count work inside loops:

- First iteration does N-1 compares, second does N-2, and so on.

- One swap per iteration

- O(N2)

Insertion sort

As sorting hand of just-dealt cards, each subsequent element inserted into proper place

- Start with first element (already sorted)

- Insert next element relative to first

- Repeat for third, fourth, etc.

- Slide elements over to make space during insert

void InsertionSort(Vector<int> &v)

{

for (int i = 1; i < v.size(); i++) {

int cur = v[i]; // slide cur down into position to left

for (int j=i-1; j >= 0 && v[j] > cur; j--)

v[j+1] = v[j];

v[j+1] = cur;

}

}

Because of the nested loops, each of which can take N iterations, insertion sort is O(N2).

Heapsort

Priority queues can be used to sort in O(N log N) time. The algorithm based on this idea is known as heapsort.

The building of the heap, uses less than 2N comparisons. In the second phase, the ith deleteMax uses at most less than 2\*log (N − i + 1) comparisons, for a total of at most 2N log N − O(N) comparisons (assuming N ≥ 2). Consequently, in the worst case, at most 2N log N − O(N) comparisons are used by heapsort.

Merge sort

Inspiration: Algorithm like selection sort is quadratic growth (O(N2)). Double input -> 4X time, halve input -> 1/4 time. Can recursion save the day? If there are two sorted halves, how to produce sorted full result?

Divide and conquer algorithm

- Divide input in half

- Recursively sort each half

- Merge two halves together

“Easy-split hard-join”

- No complex decision about which goes where, just divide in middle

- Merge step preserves ordering from each half

Merge depends on the fact that the first element in the complete ordering must be either the first element in v1 or the first element in v2, whichever is smaller.

void MergeSort(Vector<int> &v)

{

if (v.size() > 1) {

int n1 = v.size()/2;

int n2 = v.size() - n1;

Vector<int> left = Copy(v, 0, n1);

Vector<int> right = Copy(v, n1, n2);

MergeSort(left);

MergeSort(right);

v.clear();

Merge(v, left, right);

}

}

void Merge(Vector<int> &v,Vector<int> &left,Vector<int> &right) {

int l=0, r=0;

while(l<left.size() && r<right.size()) {

if (left[l]<right[r])

v.add(left[l++]);

else

v.add(right[r++]);

}

while(l<left.size()) v.add(left[l++]);

while(r<right.size()) v.add(right[r++]);

}

The time to mergesort N numbers is equal to the time to do two recursive mergesorts of size N/2, plus the time to merge, which is linear. T(N) = N + 2T(N/2). log N levels * N per level= O(NlogN). Mergesort uses the lowest number of comparisons of all the popular sorting algorithms.

Theoretical result show that no general sort algorithm could be better than NlogN.

But there is still better in practice:

- The running time of mergesort, when compared with other O(N log N) alternatives, depends heavily on the relative costs of comparing elements and moving elements in the array (and the temporary array). These costs are language dependent.

- In Java, when performing a generic sort (using a Comparator), an element comparison can be expensive, but moving elements is cheap (because they are reference assignments, rather than copies of large objects).

- In C++, in a generic sort, copying objects can be expensive if the objects are large, while comparing objects often is relatively cheap because of the ability of the compiler to aggressively perform inline optimization.

Quicksort

Most sorting programs in use today are based on an algorithm called Quicksort, which employs a Divide and conquer strategy as merge sort, but instead take a different approach to divide up input vector into low half and high half. Quicksort uses a few more comparisons, in exchange for significantly fewer data movements. The reason that quicksort is faster is that the partitioning step can actually be performed in place and very efficiently.

“Hard-split easy-join”, Each element examined and placed in correct half, so that join step become trivial.

- Choose an element (pivot) to serve as the boundary between the small and large elements.

- Partitioning: Rearrange the elements in the vector so that all elements to the left of the boundary are less than the pivot and all elements to the right are greater than or possibly equal to the pivot.

- Sort the elements in each of the partial vectors.

void Quicksort(Vector<int> &v, int start, int stop)

{

if (stop > start) {

int pivot = Partition(v, start, stop);

Quicksort(v, start, pivot-1);

Quicksort(v, pivot+1, stop);

}

}

The running time of quicksort is equal to the running time of the two recursive calls plus the linear time spent in the partition (the pivot selection takes only constant time). T(N) = T(i) + T(N − i − 1) + cN, where i = |S1| is the number of elements in S1.

There are thre cases

- Ideal 50/50 split: The pivot is in the middle, T(N) = cN + 2T(N/2) => O(NlogN)

- Average bad 90/10 split: N per level, but more levels, solve N*(9/10)k = 1, still k = O(NlogN)

- Worst N-1/1 split: The pivot is the smallest element, all the time. Then i = 0, T(N) = T(N − 1) + cN, N > 1. With N levels! O(N2)

In a vector with randomly chosen elements, Quicksort tends to perform well, with an average-case complexity of O(N log N). In the worst case — which paradoxically consists of a vector that is already sorted — the performance degenerates to O(N2). Despite this inferior behavior in the worst case, Quicksort is so much faster in practice than most other algorithms that it has become the standard.

Quicksort strategy

Picking the pivot Picking a good pivot improves performance, but also costs some time. If the algorithm spends more time choosing the pivot than it gets back from making a good choice, you will end up slowing down the implementation rather than speeding it up.

- The popular, uninformed choice is to use the first element as the pivot. This is acceptable if the input is random, but if the input is presorted or in reverse order, then the pivot provides a poor partition.

- A safe approach is to choose the pivot element randomly. On the other hand, random number generation is generally an expensive commodity and does not reduce the average running time of the rest of the algorithm at all.

- A good estimate can be obtained by picking three elements randomly and using the median of these three as pivot. The randomness turns out not to help much, so the common course is to use as pivot the median of the left, right, and center elements.

Quicksort partitioning strategy A known method that is very easy to do it wrong or inefficiently.

- General process:

- The first step is to get the pivot element out of the way by swapping it with the last element.

- Two pointers, i point to the first element and j to the next-to-last element. What our partitioning stage wants to do is to move all the small elements to the left part of the array and all the large elements to the right part. “Small” and “large” are relative to the pivot.

- While i is to the left of j, we move i right, skipping over elements that are smaller than the pivot. We move j left, skipping over elements that are larger than the pivot.

- When i and j have stopped, i is pointing at a large element and j is pointing at a small element. If i is to the left of j (not yet cross), those elements are swapped.

- Repeat the process until i and j cross

- The final is to swap the pivot element with present i element

- One important detail we must consider is how to handle elements that are equal to the pivot? Suppose there are 10,000,000 elements, of which 500,000 are identical (or, more likely, complex elements whose sort keys are identical).

- To get an idea of what might be good, we consider the case where all the elements in the array are identical.

- If neither i nor j stops, and code is present to prevent them from running off the end of the array, no swaps will be performed. Although this seems good, a correct implementation would then swap the pivot into the last spot that i touched, which would be the next-to last position (or last, depending on the exact implementation). This would create very uneven subarrays. If all the elements are identical, the running time is O(N2).

- If both i and j stop, there will be many swaps between identical elements. The partition creates two nearly equal subarrays. The total running time would then be O(N log N).

- Thus it is better to do the unnecessary swaps and create even subarrays than to risk wildly uneven subarrays.

- Small arrays

- For very small arrays (N ≤ 20), quicksort does not perform as well as insertion sort.

- Furthermore, because quicksort is recursive, these cases will occur frequently.

- A common solution is not to use quicksort recursively for small arrays, but instead use a sorting algorithm that is efficient for small arrays, such as insertion sort.

- A good cutoff range is N = 10, although any cutoff between 5 and 20 is likely to produce similar results. This also saves nasty degenerate cases, such as taking the median of three elements when there are only one or two.

Design Strategy

When an algorithm is given, the actual data structures need not be specified. It is up to the programmer to choose the appropriate data structure in order to make the running time as small as possible. There are many to be considered: algorithms, data structure, space-time tradeoff, code complexity.

Dynamic Programming

To solve optimization problems in which we make a set of choices in order to arrive at an optimal solution. As we make each choice, subproblems of the same form often arise. Dynamic programming is effective when a given subproblem may arise from more than one partial set of choices; the key technique is to store the solution to each such subproblem in case it should reappear. Unlike divide-and-conquer algorithms which partition the problem into disjoint subproblems, dynamic programming applies when the subproblems overlap.

- “Programming” in this context refers to a tabular method.

- When should look for a dynamic-programming solution to a problem?

- Optimal substructure: a problem exhibits optimal substructure if an optimal solution to the problem contains within it optimal solutions to subproblems.

- Overlapping subproblems: When a recursive algorithm revisits the same problem repeatedly, we say that the optimization problem has overlapping subproblems. In contrast, a problem for which a divide-andconquer approach is suitable usually generates brand-new problems at each step of the recursion.

- General setps of Dynamic Programming

- Characterize the structure of an optimal solution.

- Recursively define the value of an optimal solution.

- Compute the value of an optimal solution, typically in a bottom-up fashion.

- Construct an optimal solution from computed information.

Greedy Algorithms

Greedy algorithms work in phases. In each phase, a decision is made in a locally optimal manner, without regard for future consequences. When the algorithm terminates, we hope that the local optimum is equal to the global optimum. If this is the case, then the algorithm is correct; otherwise, the algorithm has produced a suboptimal solution.

- A Huffman code is a particular type of optimal prefix code that is commonly used for lossless data compression.

- The reason that this is a greedy algorithm is that at each stage we perform a merge without regard to global considerations. We merely select the two smallest trees.

- If we maintain the trees in a priority queue, ordered by weight, then the running time is O(C logC), since there will be one buildHeap, 2C − 2 deleteMins, and C − 2 inserts. A simple implementation of the priority queue, using a list, would give an O(C2) algorithm. The choice of priority queue implementation depends on how large C is. In the typical case of an ASCII character set, C is small enough that the quadratic running time is acceptable.

Divide and Conquer

Traditionally, routines in which the text contains at least two recursive calls and subproblems be disjoint (that is, essentially nonoverlapping) are called divide-and-conquer algorithms.

- Divide: Smaller problems are solved recursively (except, of course, base cases).

- Conquer: The solution to the original problem is then formed from the solutions to the subproblems.

We have already seen several divide-and-conquer algorithms: mergesort and quicksort, which have

O(N log N)worst-case and averagecase bounds, respectively.

Backtracking Algorithms

See Recursive Backtracking In some cases, the savings over a brute-force exhaustive search can be significant. The elimination of a large group of possibilities in one step is known as pruning.

How to evaluate/compare alternatives

- Often interested in execution performance: Time spent and memory used

- Should also consider ease of developing, verifying, maintaining code

Text editor case study

Buffer requirements

- Sequence of characters + cursor position

- Operations to match commands above

What to consider?

- Implementation choices

- performance implications

Buffer class interface

class Buffer { public: Buffer(); ~Buffer(); void moveCursorForward(); void moveCursorBackward(); void moveCursorToStart(); void moveCursorToEnd(); void insertCharacter(char ch); void deleteCharacter(); void display(); private: // TBD! };Buffer layered on Vector

- Need character data + cursor

- Chars in

Vector<char> - Represent cursor as integer index

- Minor detail – is index before/after cursor?

- Chars in

- Buffer contains: AB|CDE

// for Buffer class private: Vector<char> chars; int cursor;- Performance

- insertCharacter() and deleteCharacter() is linear, other operation is just O(1)

- Space used ~1 byte per char

- Need character data + cursor

Buffer layered on Stack

- Inspiration: add/remove at end of vector is fast

- If chars next to cursor were at end…

- Build on top of stack?

- Another layered abstraction!

- How is cursor represented?

- Buffer contains:AB|CDE There is no explicit cursor representation, instead using two stack to represent a whole data structure being seperated by the implicit cursor.

// for Buffer class private: Stack<char> before, after;- Performance

- moveCursorToStart(), moveCursorToEnd() operation is linear, other operation is just O(1)

- Space used ~2 byte per char

- Inspiration: add/remove at end of vector is fast

Buffer as double linked list

- Inspiration: contiguous memory is constraining

- Connect chars without locality

- Add tail pointer to get direct access to last cell

- Add prev link to speed up moving backwards

- Buffer contains:AB|CDE

// for Buffer class private: struct cellT { char ch; cellT *prev, *next; }; cellT *head, *tail, *cursor;- Cursor design

- To cell before or after?

- 5 letters, 6 cursor positions…

- Add “dummy cell” to front of list

- Performance

- destruction is linear, other operation is just O(1)

- Space used ~9 byte per char

- Inspiration: contiguous memory is constraining

Compare implementations

| Operation | Vector | Stack | Single linked list | Double linked list |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer() | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) |

| ~Buffer() | O(1) | O(1) | O(N) | O(N) |

| moveCursorForward() | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) |

| moveCursorBackward() | O(1) | O(1) | O(N) | O(1) |

| moveCursorToStart() | O(1) | O(N) | O(1) | O(1) |

| moveCursorToEnd() | O(1) | O(N) | O(N) | O(1) |

| insertCharacter() | O(N) | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) |

| deleteCharacter() | O(N) | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) |

| Space used | 1N | 2N | 5N | 9N |

- Space-time tradeoff

- Doubly-linked list is O(1) on all six operations

- But, each char uses 1 byte + 8 bytes of pointers => 89% overhead!

- Compromise: chunklist

- Array and linked list hybrid

- Shares overhead cost among several chars

- Chunksize can be tuned as appropriate

- Cost shows up in code complexity

- Cursor must traverse both within and across chunks

- Splitting/merging chunks on insert/deletes

- Doubly-linked list is O(1) on all six operations

Map

Map is super-useful, support any kind of dictionary, lookup table, index, database, etc. Map stores key-value pairs, support fast access via key, operations to optimize: add, getValue How to make it work efficiently?

- Implement Map as Vector

- Layer on Vector, provides convenience with low overhead

- Define pair struct, to olds key and value together,

Vector<pair> - Vector sorted or unsorted? If sorted, sorted by what?

- Sorting: Provides fast lookup, but still slow to insert (because of shuffling)

- How to implement getValue, add?

- Does a linked list help?

- Easy to insert, once at a position

- But hard to find position to insert…

- Implementing Map as tree

- Implementatation

- Each Map entry adds node to tree, node contains: string key, client-type value, pointers to left/right subtrees

- Tree organized for binary search, Key is used as search field

- getValue: Searches tree, comparing keys, find existing match or error

- add: Searches tree, comparing keys, overwrites existing or adds new node

- Private members for Map

template <typename ValType> class Map { public: // as before private: struct node { string key; ValType value; node *left, *right; }; node *root; node *treeSearch(node * t, string key); void treeEnter(node *&t, string key, ValType val); DISALLOW_COPYING(Map) };- Evaluate Map as tree

- Space used: Overhead of two pointers per entry (typically 8 bytes total)

- Runtime performance: Add/getValue take time proportional to tree height(expected to be O(logN))

- Degenerate trees

- The insert order is “sorted”: 2 8 14 15 18 20 21, totally unbalanced with height = 7

- The insert order is “alternately sorted”: 21 2 20 8 14 15 18 or 2 8 21 20 18 14 15

- Association: What is the relationship between worst-case inputs for tree insertion and Quicksort?

- What to do about it: AVL tree

- Implementatation

- Compare Map implementations

| Operation | Vector | BST | Sorted Vector |

|---|---|---|---|

| getValue | O(N) | O(lgN) | O(lgN) |

| add | O(N) | O(lgN) | O(N) |

| Space used | N | 9N | N |

Hashing

- Hash table ADT

- Hash table data structure: A list of keys and TableSize

- Hash function: A mapping that map each key into some number in the range 0 to TableSize-1 and distributes the keys evenly among the appropriate cell

- Hashing The major problems are choosing a function, deciding what to do when two keys hash to the same value (this is known as a collision), and deciding on the table size

- Rehashing If the table gets too full, the running time for the operations will start taking too long, and insertions might fail for open addressing hashing with quadratic resolution. A solution is to build another table that is about twice as big (with an associated new hash function) and scan down the entire original hash table, computing the new hash value for each (nondeleted) element and inserting it in the new table.

The Big-Five

In C++11, classes come with five special functions that are already written for you. These are the destructor, copy constructor, move constructor, copy assignment operator, and move assignment operator. Collectively these are the big-five.

Destructor

The destructor is called whenever an object goes out of scope or is subjected to a delete. Typically, the only responsibility of the destructor is to free up any resources that were acquired during the use of the object. This includes calling delete for any corresponding news, closing any files that were opened, and so on. The default simply applies the destructor on each data member.

Constructor

A constructor is a method that describes how an instance of the class is constructed. If no constructor is explicitly defined, one that initializes the data members using language defaults is automatically generated.

Copy Constructor and Move Constructor

Copy Assignment and Move Assignment (operator=) By Defaults, if a class consists of data members that are exclusively primitive types and objects for which the defaults make sense, the class defaults will usually make sense. The main problem occurs in a class that contains a data member that is a pointer.

- The default destructor does nothing to data members that are pointers (for good reason—recall that we must delete ourselves).

- Furthermore, the copy constructor and copy assignment operator both copy the value of the pointer rather than the objects being pointed at. Thus, we will have two class instances that contain pointers that point to the same object. This is a so-called shallow copy (contrast to deep copy).

- To avoid shallow copy, ban the copy funtionality by calling

DISALLOW_COPYING(ClassType).

As a result, when a class contains pointers as data members, and deep semantics are important, we typically must implement the destructor, copy assignment, and copy constructors ourselves.

Explicit constructor: All one-parameter constructors should be made explicit to avoid behind-the-scenes type conversions. Otherwise, there are somewhat lenient rules that will allow type conversions without explicit casting operations. Usually, this is unwanted behavior that destroys strong typing and can lead to hard-to-find bugs. The use of explicit means that a one-parameter constructor cannot be used to generate an implicit temporary

class IntCell {

public:

explicit IntCell( int initialValue = 0 )

: storedValue{ initialValue } { }

int read( ) const

{ return storedValue; }

private:

int storedValue;

};

IntCell obj; // obj is an IntCell

obj = 37; // Should not compile: type mismatch

Since IntCell constructor is declared explicit, the compiler will correctly complain that there is a type mismatch

Template

Type-independent

When we write C++ code for a type-independent algorithm or data structure, we would prefer to write the code once rather than recode it for each different type

Function template

- A function template is not an actual function, but instead is a pattern for what could become a function.

- An expansion for each new type generates additional code; this is known as code bloat when it occurs in large projects.

Class template

template <typename Object>

class MemoryCell {

public:

explicit MemoryCell( const Object & initialValue = Object{ } )

: storedValue{ initialValue } { }

private:

Object storedValue;

};

MemoryCell is not a class, it is only a class template. It will be a class if specify the Object type. MemoryCell<int> and MemoryCell<string> are the actual classes.

Graph Algorithms

Definitions: vertices, edges, arcs, directed arcs = digraphs, weight/cost, path, length, acyclic(no cycles)

Topological Sort

- A topological sort is an ordering of vertices in a directed acyclic graph, such that if there is a path from vi to vj, then vj appears after vi in the ordering.

- A topological ordering is not possible if the graph has a cycle

- To find a topological ordering, define the indegree of a vertex v as the number of edges (u, v), then use a queue or stack to keep the present 0 indegree vertexes. At each stage, as long as the queue is not empty, dequeue a 0 indegree vertexes in the queue, enqueue each new generated 0 indegree vertexes into the queue.

Shortest-Path Algorithms

- Explores equally in all directions

- To find unweighted shortest paths

- Operates by processing vertices in layers: The vertices closest to the start are evaluated first, and the most distant vertices are evaluated last.

- Also called Uniform Cost Search, cost matters

- Instead of exploring all possible paths equally, it favors lower cost paths.

- Dijkstra’s algorithm proceeds in stages. At each stage, while there are still vertices waiting to be known:

- Selects a vertex v, which has the smallest dv among all the unknown vertices, and declares v as known stage.

- For each of v’s neighbors, w, if the new path’s cost from v to w is better than previous dw, dw will be updated.

- But w will not be marked as known, unless at next while-loop stage, dw happens to be the smalles.

- The above steps could be implemented via a priority queue.

- A proof by contradiction will show that this algorithm always works as long as no edge has a negative cost.

- If the graph is sparse, with |E| =θ(|V|), this algorithm is too slow. In this case, the distances would need to be kept in a priority queue. Selection of the vertex v is a deleteMin operation. The update of w’s distance can be implemented two ways.

- One way treats the update as a decreaseKey operation.

- An alternate method is to insert w and the new value dw into the priority queue every time w’s distance changes.

Greedy Best First Search(Heuristic search)

- With Breadth First Search and Dijkstra’s Algorithm, the frontier expands in all directions. This is a reasonable choice if you’re trying to find a path to all locations or to many locations. However, a common case is to find a path to only one location.

- A modification of Dijkstra’s Algorithm, optimized for a single destination. It prioritizes paths that seem to be leading closer to the goal.

- To make the frontier expand towards the goal more than it expands in other directions.

- First, define a heuristic function that tells us how close we are to the goal, design a heuristic for each type of graph

def heuristic(a, b): # Manhattan distance on a square grid return abs(a.x - b.x) + abs(a.y - b.y)- Use the estimated distance to the goal for the priority queue ordering. The location closest to the goal will be explored first.

- This algorithm runs faster when there aren’t a lot of obstacles, but the paths aren’t as good(not always the shortest).

- Dijkstra’s Algorithm works well to find the shortest path, but it wastes time exploring in directions that aren’t promising. Greedy Best First Search explores in promising directions but it may not find the shortest path.

- The A* algorithm uses both the actual distance from the start and the estimated distance to the goal.

- Compare the algorithms: Dijkstra’s Algorithm calculates the distance from the start point. Greedy Best-First Search estimates the distance to the goal point. A* is using the sum of those two distances.

- So A* is the best of both worlds. As long as the heuristic does not overestimate distances, A* does not use the heuristic to come up with an approximate answer. It finds an optimal path, like Dijkstra’s Algorithm does. A* uses the heuristic to reorder the nodes so that it’s more likely that the goal node will be encountered sooner.

Conclusion: Which algorithm should you use for finding paths on a map?

- If you want to find paths from or to all all locations, use Breadth First Search or Dijkstra’s Algorithm. Use Breadth First Search if movement costs are all the same; use Dijkstra’s Algorithm if movement costs vary.

- If you want to find paths to one location, use Greedy Best First Search or A*. Prefer A* in most cases. When you’re tempted to use Greedy Best First Search, consider using A* with an “inadmissible” heuristic.

- If you want the optimal paths, Breadth First Search and Dijkstra’s Algorithm are guaranteed to find the shortest path given the input graph. Greedy Best First Search is not. A* is guaranteed to find the shortest path if the heuristic is never larger than the true distance. (As the heuristic becomes smaller, A* turns into Dijkstra’s Algorithm. As the heuristic becomes larger, A* turns into Greedy Best First Search.)

Advanced Data Structures

Red-Black Trees

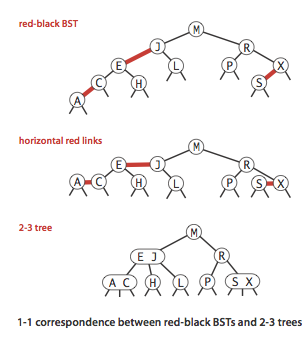

Red-black tree leads to a natural implementation of the insertion algorithm for 2-3 trees

RBT definition

- Red-black tree means encoding 2-3 trees in this way: red links, which bind together two 2-nodes to represent 3-nodes, and black links, which bind together the 2-3 tree.

- An equivalent definition is to define red-black BSTs as BSTs having red and black links and satisfying the following three restrictions:

- Red links lean left.

- No node has two red links connected to it.

- The tree has perfect black balance : every path from the root to a null link has the same number of black links.

- A 1-1 correspondence: If we draw the red links horizontally in a red-black BST, all of the null links are the same distance from the root, and if we then collapse together the nodes connected by red links, the result is a 2-3 tree.

RBT implementaion

- Color representation:

- Each node is pointed to by precisely one link from its parent,

- Encode the color of links in nodes, by adding a boolean instance variable color to our Node data type, which is true if the link from the parent is red and false if it is black. By convention, null links are black.

- For clarity, define constants

REDandBLACKfor use in setting and testing this variable.

- Rotation

To correct right-leaning red links or two red links in a row conditions.

- takes a link to a red-black BST as argument and, assuming that link to be to a Node h whose right link is red, makes the necessary adjustments and returns a link to a node that is the root of a red-black BST for the same set of keys whose left link is red. Actually it is switching from having the smaller of the two keys at the root to having the larger of the two keys at the root.

- Flipping colors

- to split a 4-node

- In addition to flipping the colors of the children from red to black, we also flip the color of the parent from black to red.

- Keeping the root black.

- Insertion

Maintain the 1-1 correspondence between 2-3 trees and red-black BSTs during insertion by judicious use of three simple operations: left rotate, right rotate, and color flip.

- If the right child is red and the left child is black, rotate left.

- If both the left child and its left child are red, rotate right.

- If both children are red, flip colors.

- Deletion

- Color representation:

Assignments

- Name Hash

- Game of Life

- Serafini

- Recursion

- Boggle!

- Patient Queue

- Huffman Encoding

- Trailblazer