Reward modeling (RM) has emerged as a cornerstone of large language model (LLM) alignment, guiding models to align with human values and perform complex tasks. Early approaches relied heavily on Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), but recent research has shifted toward more scalable, efficient, and generalizable RM frameworks. This blog explores the developmental arc of RM, connecting four seminal papers that have shaped the field: from human labeled preference to AI feedback, from Generative Reward Models(GRM) to inference-time scaling for GRM.

Scoring human preference by parameters

Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback1 presents a reward modeling (RM) approach as a core component of reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) to align language models with human intent. Below is a detailed breakdown of the paper’s views and methods on reward modeling:

Core Objectives of Reward Modeling

The reward model aims to:

- Quantify Human Preferences: Convert subjective human judgments about model outputs into a scalar reward signal, enabling models to learn what constitutes “desirable behavior.”

- Guide Model Alignment: Direct language models to follow instructions, prioritize truthfulness, and avoid harmful outputs by optimizing against human-derived rewards.

Data Collection for Reward Modeling

- Input Source: Prompts from the OpenAI API (filtered to remove PII) and labeler-written prompts, covering tasks like generation, QA, and summarization .

- Labeling Process:

- Labelers rank 4–9 model outputs per prompt from best to worst, generating pairwise comparisons (e.g., “Output A is preferred over Output B”) .

- To avoid bias, labelers undergo a screening test to assess sensitivity to sensitive content and alignment with research criteria .

Reward Model Architecture and Training

Model Structure:

- Based on the GPT-3 architecture, initialized from a supervised fine-tuned (SFT) model with the final unembedding layer replaced by a projection layer to output a scalar reward .

- Uses a 6B parameter model for computational efficiency, as 175B models showed training instability .

Training Methodology:

- Loss Function: Cross-entropy loss to predict human-preferred outputs, formulated as: $$ \text{loss}(\theta) = -\frac{1}{\binom{K}{2}} \mathbb{E}_{\left(x, y_w, y_l\right) \sim D} \left[ \log \left( \sigma(r_\theta(x, y_w) - r_\theta(x, y_l)) \right) \right] $$ where $y_w$ and $y_l$ are the preferred and less preferred outputs, respectively, and $K$ is the number of outputs per prompt .

- Batch Processing: Treats all $\binom{K}{2}$ comparisons from a prompt as a single batch element to prevent overfitting and improve computational efficiency .

- Normalization: Adjusts rewards so that labeler demonstrations have a mean score of 0 before RL training .

Conclusion

In summary, the paper demonstrates that reward modeling via RLHF is a powerful tool for aligning language models, but ongoing research is needed to address its limitations and expand its applicability to diverse human values.

Key Innovations and Insights:

- Generalization to Held-Out Labelers: Reward models trained on one group of labelers generalize to new labelers, with cross-validation showing 69.6% accuracy in predicting preferences of unseen labelers .

- Trade-off with Public NLP Datasets: RM-based RLHF may cause performance regressions on standard NLP tasks (e.g., SQuAD, DROP), but mixing pretraining gradients (PPO-ptx) mitigates this while preserving human preference .

- Role in InstructGPT: The RM is crucial for improving model behavior: InstructGPT (PPO-ptx) outperforms GPT-3 despite having 100x fewer parameters, with 1.3B InstructGPT preferred over 175B GPT-3 in 85% of cases .

Limitations and Future Directions:

- Alignment Scope: The RM aligns models to specific labelers and researchers, not broader human values, raising questions about fairness and representativeness .

- Toxicity and Bias: While InstructGPT reduces toxicity, it shows minimal improvement on bias metrics (e.g., Winogender, CrowS-Pairs), indicating RM needs better signals for these dimensions .

- Scalability: Future work may explore combining RM with adversarial data collection or constraint optimization to address harmful outputs and improve generalization .

Scoring preference provided by AI

2. : Bootstrapping Harmlessness with AI Feedback

Constitutional AI2 introduced a paradigm that replaces human labels for harmfulness with AI-generated feedback. The approach uses a “constitution” of principles to guide self-critique and revision, enabling models to learn harmless behavior without direct human supervision.

- Key Innovation: The framework combines supervised learning (critique → revision cycles) and RL from AI Feedback (RLAIF), where a preference model (PM) is trained on AI-generated comparisons. For example, models generate pairs of responses and evaluate which aligns better with constitutional principles (e.g., “avoid harmful advice”).

- Impact: As shown in Figure 2 of the paper, Constitutional AI achieves a Pareto improvement in harmlessness and helpfulness, outperforming RLHF models that trade off these traits. The approach reduces reliance on human labeling, a critical step toward scalable supervision.

This work laid the groundwork for self-supervised RM, demonstrating that models can learn to evaluate their own behavior using explicit principles.

Rule Based Rewards

DeepSeek-R13 employs reward modeling strategically to enhance reasoning capabilities in LLMs through reinforcement learning (RL).

DeepSeek-R1-Zero relies on a rule-based reward system to avoid the complexity and potential pitfalls of neural reward models. This system consists of two main components:

- Accuracy Rewards: Evaluate the correctness of responses. For example:

- In math problems, the model must provide answers in a specified format (e.g., within a box) for rule-based verification.

- In coding tasks (e.g., LeetCode), a compiler checks solutions against predefined test cases.

- Format Rewards: Enforce structural consistency by requiring the model to place reasoning processes between specific tags (e.g.,

<think>,<\think>,<|tool▁calls▁begin|><|tool▁call▁begin|>and<|tool▁call▁end|><|tool▁calls▁end|><|end▁of▁sentence|>).

The paper explicitly avoids neural reward models (both outcome and process-based) for DeepSeek-R1-Zero, citing risks of reward hacking and the additional computational overhead of retraining reward models.

DeepSeek-R1 incorporates additional reward mechanisms to address readability and generalizability:

- Language Consistency Reward: Introduced to mitigate language mixing in Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. This reward measures the proportion of target language words in the CoT and is summed with accuracy rewards. While this slightly reduces reasoning performance, it improves human readability.

- Multi-Stage RL with Diverse Rewards:

- Reasoning-Oriented RL: Uses rule-based rewards (accuracy + format) for tasks like math and coding.

- General Scenario RL: Employs neural reward models to align with human preferences for helpfulness and harmlessness. For example:

- Helpfulness: Focuses on the utility of the final summary.

- Harmlessness: Evaluates the entire response (reasoning + summary) to prevent biased or harmful content.

Thousands of cold start CoT examples are curated to fine-tune the model before RL. These examples include human-readable formats (e.g., summaries) and serve as a foundation for reward-aligned behavior.

Key Trade-offs and Design Choices

- Rule-Based vs. Neural Rewards: Rule-based rewards are prioritized for simplicity and to avoid reward hacking in large-scale RL. Neural rewards are introduced only when necessary (e.g., for general task alignment in DeepSeek-R1).

- Balancing Performance and Readability: The language consistency reward in DeepSeek-R1 trades off slight performance degradation for improved human interpretability, highlighting the importance of practical usability.

Conclusion

DeepSeek-R1 demonstrates that reward modeling in RL can be tailored to balance reasoning performance, readability, and human alignment. Rule-based rewards enable pure RL-driven reasoning emergence in DeepSeek-R1-Zero, while DeepSeek-R1 enhances this with language consistency and general preference rewards. This approach highlights the flexibility of reward systems in shaping LLM behavior without heavy reliance on neural reward models, paving the way for efficient and interpretable reasoning enhancements.

Generative Reward Modeling (GRM)

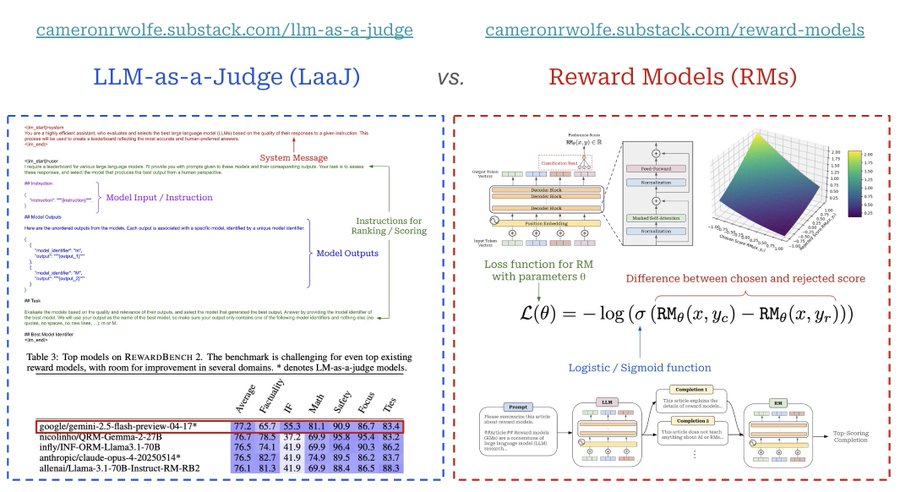

LLM-as-a-Judge4 Framework proposes three evaluation methods: pairwise comparison (judging which of two answers is better), single-answer grading (assigning scores to individual answers), and reference-guided grading (using reference solutions for tasks like math). LLM judges offer scalability (reducing reliance on costly human evaluations) and explainability (providing detailed rationales).

Showing strong alignment between LLM judges (e.g., GPT-4) and human preferences, with over 80% agreement—matching the agreement level between humans. GPT-4, in particular, demonstrates high consistency with both expert and crowdsourced human judgments.

Biases in LLM judges:

- position bias (favoring certain positions): Mitigations include swapping answer positions.

- verbosity bias (preferring longer responses)

- self-enhancement bias (favoring their own outputs)

Compariso with Reward Models (RMs):

| Aspect | LLM-as-a-Judge (LaaJ) | Reward Models (RMs) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A reference-free evaluation metric using a powerful LLM (prompted to assess outputs) | Specialized LLMs (derived from the model being trained) fine-tuned to predict human preference scores for a prompt and completion |

| Scoring Capabilities | - Direct assessment scores (binary, Likert) - Pairwise comparisons of multiple outputs - Arbitrary scoring setups (high flexibility) | - Scores single outputs (preference scores derived via models like Bradley-Terry for multiple outputs) - Higher score = more likely human-preferred |

| Model Basis | Often off-the-shelf/foundation LLMs; can be fine-tuned or ensembled into a “jury” | Always fine-tuned, usually derived from the LLM being trained |

| Training | Fine-tuned via standard language modeling objectives (if fine-tuned) | Fine-tuned using preference learning or ranking objectives |

| Architecture | Standard LLM architecture | Standard LLM with an additional classification head for predicting preference scores |

| Key Use Cases | Evaluation (direct assessment and pairwise); high accuracy in evaluation | RL-based training (e.g., PPO-based RLHF); must be custom-trained for the current policy |

| Flexibility | More flexible (supports arbitrary scoring setups) | Less flexible (primarily scores single outputs) |

iamge from https://x.com/cwolferesearch/status/1945540243056144420/photo/1

iamge from https://x.com/cwolferesearch/status/1945540243056144420/photo/1

Inference-Time Scaling of GRM

Self-Principled Critique Tuning (SPCT)5 combines generative reward modeling (GRM) with inference-time scaling to improve RM performance without increasing training compute. SPCT builds on Constitutional AI’s self-critique and DeepSeek-R1’s RL efficiency, but shifts focus to generalist domains. The meta RM integrates self-evaluation insights (from Kadavath et al.) to filter low-quality rewards, aligning with P(IK)-like confidence metrics.

- SPCT: A two-phase RL method where models learn to generate adaptive principles and critiques, enhancing reward quality. For example, DeepSeek-GRM-27B with SPCT outperforms scalar RMs on benchmarks like Reward Bench and PPE (Table 2).

- Inference-Time Scaling: Parallel sampling and a meta RM guide voting on multiple reward samples, expanding the reward space and improving granularity. As shown in Figure 1, DeepSeek-GRM-27B with meta RM achieves 72.8% overall performance, surpassing models like Nemotron-4-340B-Reward.

Conclusion

The landscape of reward modeling is evolving rapidly, driven by innovations that prioritize scalability, self-supervision, and generalizability. From Constitutional AI’s principles to SPCT’s inference-time scaling, these methods collectively push LLMs toward more aligned, transparent, and efficient behavior. As shown in the comparative results across papers, the field is moving toward a future where RM serves as a versatile interface for LLM alignment, enabling models to reason, evaluate, and adapt to diverse human needs.

The evolution of RM reflects a shift from human-dependent, task-specific approaches to self-supervised, generalizable frameworks:

- Early RLHF (2020s): Relied on massive human labeling, limited to specific domains.

- Constitutional AI (2022): Introduced AI-generated feedback and principles, reducing human overhead.

- Generative Reward Models(GRM) (2023): a reference-free evaluation metric that assesses model outputs by simply prompting a powerful language model to perform the evaluation for us.

- Rule based reward (2025): Optimized reasoning via RL, demonstrating task-specific RM scaling.

- Generalist Inference-Time Scaling (2025): Extended RM to diverse domains using generative models and inference-time compute, balancing efficiency and performance.

Challenges and Future Directions

- Bias and Calibration: While SPCT reduces domain bias, models like DeepSeek-GRM still struggle with specific tasks (e.g., verifiable problems, Appendix B).

- Computational Overhead: Inference-time scaling requires more compute per query, necessitating efficiency improvements.

- Cross-Domain Generalization: Combining task-specific RM (DeepSeek-R1) with generalist GRM (Liu et al.) remains an open challenge.

Future work may integrate self-supervised RM with external tools (e.g., code execution for verification) and explore hybrid frameworks that balance training and inference-time scaling.

Ouyang, Long, et al. Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback. arXiv:2203.02155, arXiv, 4 Mar. 2022. arXiv.org, http://arxiv.org/abs/2203.02155. ↩︎

Bai, Yuntao, et al. Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback. arXiv:2212.08073, arXiv, 15 Dec. 2022. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.08073. ↩︎

DeepSeek-AI, et al. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv:2501.12948, arXiv, 22 Jan. 2025. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.12948. ↩︎

Zheng, Lianmin, et al. Judging LLM-as-a-Judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena. arXiv:2306.05685, arXiv, 24 Dec. 2023. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.05685. ↩︎

Liu, Zijun, et al. Inference-Time Scaling for Generalist Reward Modeling. arXiv:2504.02495, arXiv, 5 Apr. 2025. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.02495. ↩︎